David Wilson Interviews: Two

The Bosstown Sound and Folk Turns Political

By: Charles Giuliano and David Wilson - Nov 05, 2010

Charles Giuliano From 1964 to 1966 I worked in the basement of the Egyptian Department of the Museum of Fine Arts. I attended graduate school at NYU that fall. I left the Institute of Fine Arts after just a semester. I ran a cooperative art gallery on 57th Street, Spectrum Gallery, for a year and then worked for East Hampton Gallery where I organized the first psychedelic art exhibition. Grove Press turned my exhibition into the book Psychedelic Art.

By the Spring of 1968 I left New York and hit the road with Arden Harrison. We were going to visit her relatives in Mexico. We got as far as New Orleans and returned to Boston dead broke to work for Avatar. We paid our Fort Hill rent selling Avatar for a quarter in Harvard Square.

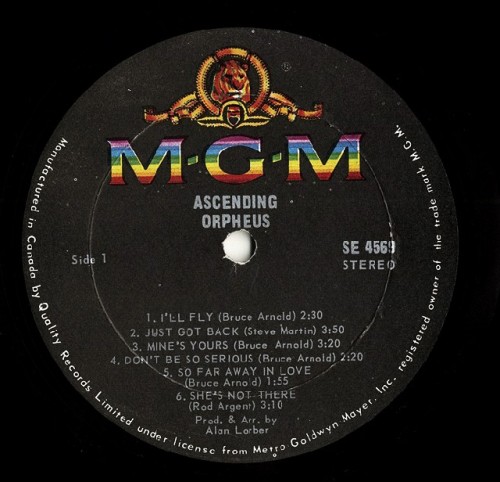

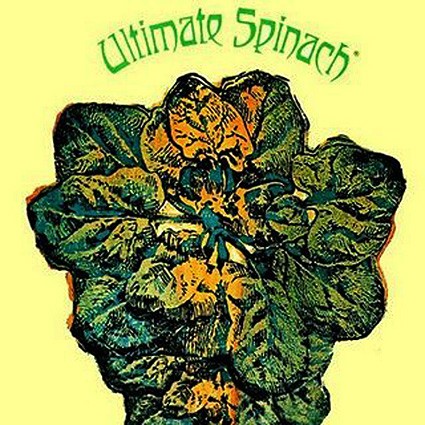

That summer was the Bosstown Sound of MGM Records under Mike Curb. There were hippie concerts on the Common as well as a few riots.

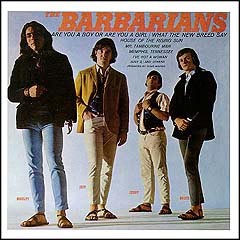

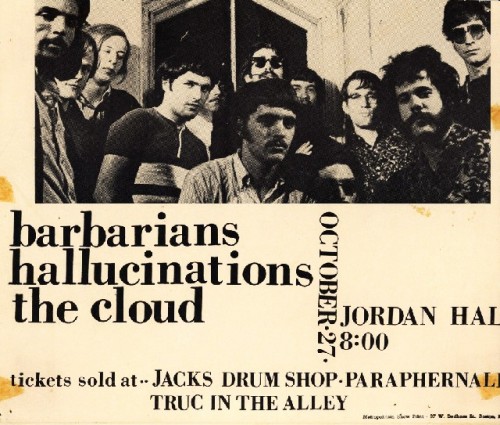

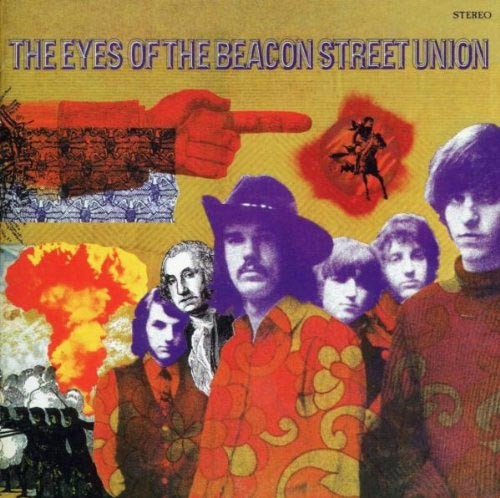

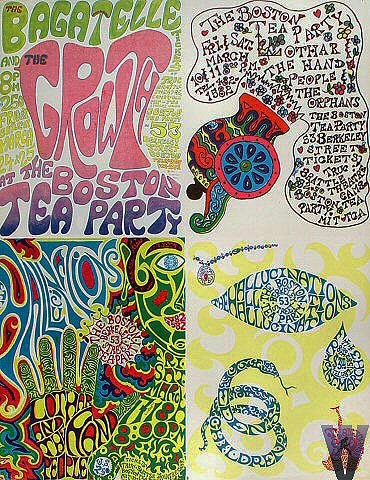

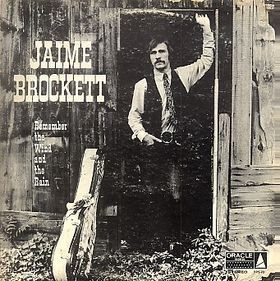

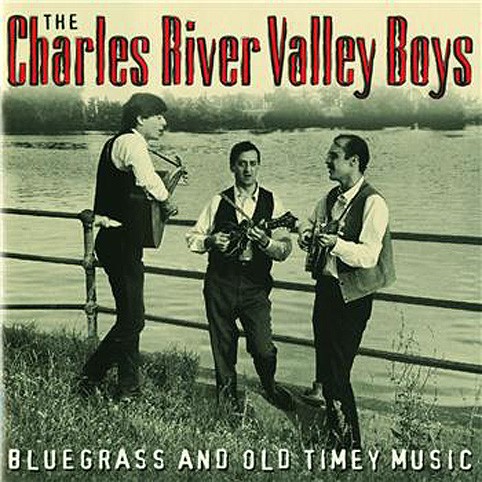

Do you remember Jamie Brockett, Ultimate Spinach, Beacon Street Union, Orpheus, Charles River Valley Boys, The Remains, The Lost, Willie Loco Alexander, The Barbarians, The Hallucinations, and other groups which played at the original Tea Party?

David Wilson Jaime Brockett: I was not a big fan and he seemed to make his big splash with a song that was at the time a copy of a song in Chris Smither’s repertoire about the Titanic. Chris was quite bitter for a while about Brockett’s brazen hijacking of his rendition and arrangement. Then one day he decided that the theft was “the removal of an albatross” because he did not have to perform it anymore and was free to do other material.

Ultimate Spinach, Orpheus and Beacon Street Union were all label manufactured, local groups which formed the basis for the Bosstown Sound. Priscilla DiDonato, who did cartoons for Broadside, was with the Spinach. I worked for a while with the agency, (along with Don Law) Music Productions, that developed Barry and the Remains. They, and the Barbarians, were the first hot ‘60s Boston rockers. I designed and produced the Remains first brochure. I introduced Ed Freeman who did a column for us to them. He did a more contemporary brochure and then ended up being their roadie when they went on tour with the Beatles. When I was managing the Odyssey Coffeehouse, on Hancock St, I gave the Hallucinations their first steady gig on the basis of a door split. Peter Wolf was the lead singer for the Hallucinations. Doug Slade played bass and the artist, Paul Shapiro, played guitar. Peter was one of the first DJ’s for WBCN and went on to join the J. Geils Band.

I do not think that the Charles River Valley Boys, anymore than the Kweskin Jug Band, can be considered part of the Bosstown Sound. The CRVB released their first US recording in 62 on the Mt. Auburn label, though I believe they had an earlier one in the UK. They went through a fair number of lineup changes in their time.

Willie Loco rings no bells.

CG Willie Loco was with The Lost. I heard the band at the Cheetah in New York. Later Willie joined The Velvet Underground. He continues to be an important fixture in the Boston music community. Did you and Broadside have anything to do with covering The Bosstown Sound?

DW We did cover much of it especially in so far as the groups sprung out of the folk tradition. It was tricky at that time trying to stay true to our traditional music readership and the fringes where folk was fusing with Psychedelic, Metal, Pop, Country, Gospel and what-all.

CG Ultimately the Bosstown Sound flopped and for a time that seemed like it for the Boston music scene.

DW While that first flowering died off, it did lead the way for a lot of other great groups including Boston, J. Geils, The Cars, and Aerosmith to mention just a few.

One difficulty I am having here is that you seem to see the ‘60s as a much more unified period then I do.

CG Can you flesh that out?

DW The early sixties was culturally, politically and aesthetically quite different from the late sixties and the change, while rapid and dynamic, was organic. Not the least was the freedom that came with the appearance of the contraceptive pill in 1960. That resulted in huge changes in lifestyle and attitude.

I was let-go from the Air Force pilot training program during a RIF in June of 1960. It was during the presidential campaign which eventually came down to Kennedy & Nixon. Later that summer I got a job working in a Top Value Stamp Warehouse, (remember those?) in Needham. I hadn’t any idea what I wanted to do or what course to take.

Kennedy got elected. I took an apartment in Boston, lost my TV stamp job, and got another as a parts inventory clerk at a tractor company in Cambridge. At a meeting of the Folksong Society of Boston I signed up to help out on the program committee and left that meeting as the Program Director and not knowing zilch about it. But I knew that the Society’s platform was of value to performers and I used the position to get to know, and have access to, a lot of the performers around town. Camelot was in blossom. Fresh air and change seemed to be the order of the day and the atmosphere seemed full of hope.

While in the Air Force I roomed with Harold Ward, an African-American, for whom I had great respect and regarded warmly. I was frustrated that we were unable to go together to many places off the base. He wasn't allowed in white establishments, and he said he couldn't vouch for my safety in his. I hated the system that maintained this state.

After Kennedy’s election, the sit-ins, the wade-ins and all the other demonstrations became a major cause for me. Folk Music was a large component of the struggle. With the connections I had, as Program Director for the Folk Song Society, it was a big help in gathering the info I needed to start publishing Broadside. Originally, I had intended to call it Funky, but few people I mentioned it to knew what that meant, so I chose Broadside. I didn’t know that in New York and in LA, in that same month, two other Broadsides had started publishing.

The Newbury St. apartment became a hangout for musicians and associates. Folks would gather there after the clubs closed and jam until early hours and out of town musicians would crash there on weekends. Months would go by without there being a 24 hour stretch where only I and my roommates were resident. At the same time, friends from pilot training who had graduated were visiting me and telling me about the secret war that was going on in Vietnam. I had a sense that we were rushing madly into chaos. People I tried to tell about it refused to believe me and in my family I was considered a bit unbalanced.

CG What role did Club 47 have in these developments?

DW Club 47 was the center of controversy. A scheduled benefit for the Sane, (Committee for a Sane Nuclear Policy) had drawn the iron hand of the Cambridge political structure down on them. They were besieged by inspectors of every conceivable type, suspending their permits, and threatening permanent closure. So much for free speech. The community rallied, legal aid was freely proffered, and eventually the club reopened. In many ways the founders were scarred by the event. The venue became more exclusive and in some ways a bit paranoid. I was persona non grata there for most of the decade due to an unflattering review for some event or other. Distribution of Broadside was suspended on the grounds that they were non-profit. Because of our 10 cent cover price they could not sell our issues.

Pot was becoming common and more so among musicians. Narcs infiltrated the scene and busted people. They held their futures hostage unless they would inform on friends. Disillusionment and paranoia was on the rise. I lost a couple of close musician friends because I made house rules barring pot from the premises. With the wholesale gatherings going on and seldom knowing half the people there at any moment, I was unwilling to take chances.

In August of 1962 Broadside moved to a big duplex house on Columbia Street in Cambridge. We had one side and the crew running the Café Yana had the other side. They were putting up the out of town musicians playing the club. I was constantly meeting more and more of the national performers. It was at that house that Dave Van Ronk and Bob Lurtsema, (Robert J. Lurtsema the renowned late classical music DJ at WGBH-FM), first came into our life.

Another change occurred when I chanced to share a table at lunch with George Hite. Our conversation, sparse at first, developed as he began to ask me about my aspirations. I told him I was interested in becoming a writer and he wanted to know what kind. I mentioned journalism, fiction, and maybe even technical writing. Over the next two months as we occasionally shared a table he offered me a job at his electronics manufacturing company, Krohn-Hite, in Central Square. I eventually agreed, gave notice and went to work for him. He started me on the assembly line to learn about the product line.

When the Cuban crisis got me activated, and threatened my still iffy economics, I became more anti-establishment and politically radical. Not that that was an unknown position for me. In high school I was considered a bohemian. At BU I was labeled a beatnik. In years to come I was going to be tagged as folknik and hippie, as well as commie, and freak. After a while the names don’t mean anything.