Beethoven, Fidelio, part I

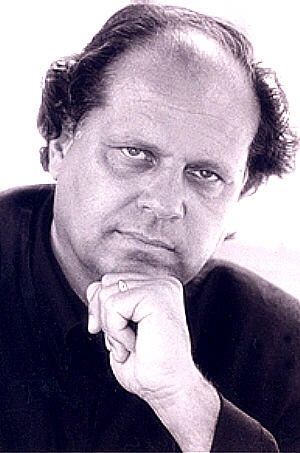

James Levine, the Boston Symphony, and a dream cast set a new standard for Boston opera in concert

By: Michael Miller - Apr 02, 2007

Ludwig van Beethoven, Fidelio, op. 72Boston Symphony Orchestra, Symphony Hall

Sunday, March 25, 2007

James Levine, conductor

Christine Brewer, (Leonore)

Lisa Milne, soprano (Marzelline)

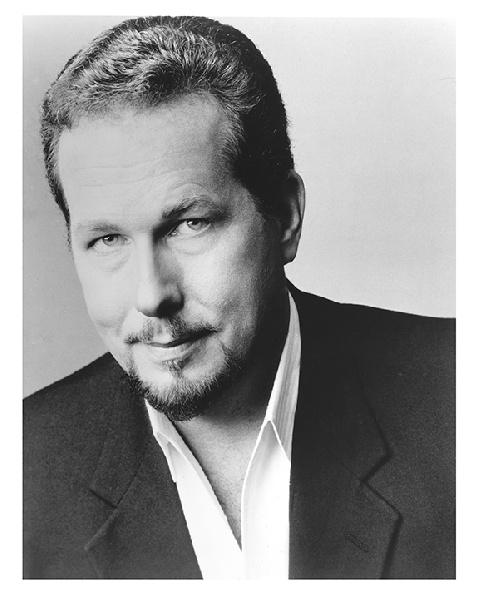

Johan Botha, tenor (Florestan)

Matthew Polenzani, tenor (Jaquino)

Albert Dohmen, bass-baritone, (Pizarro)

James Morris, bass-baritone (Don Fernando)

Robert Lloyd , bass (Rocco)

William Hite, (First Prisoner)

Robert Honeysucker, (Second Prisoner)

Tanglewood Festival Chorus

John Oliver, conductor

Concert performances of opera are nothing new to the Boston Symphony. Erich Leinsdorf was an old hand in the pit, and Seiji Ozawa liked to indulge in opera as well. However, under James Levine the BSO is entering a new phase, in which opera has become a staple in the repertory. Opera and theatrical music will be so prominent at Tanglewood this summer that they will pretty much set the tone for the entire season. Since this comes from Levine's long-going and passionate love of the art, and since he clearly has a precise idea of what he wants to accomplish with these expensive events, it is all to the better. What's more, they are extremely popular. Tickets for last week's performances of Beethoven's Fidelio were hard to come by.

It is as true today as it was a generation or two ago, in spite of the impressive rise in the standards of opera orchestras in North America, shown above all by Levine's achievement with the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra, that a conductor still can achieve a more controlled and focused performance in concert than in the house. At the very least the musicians are liberated from the restrictions of stage action and scene changes—which obviously brings more of a pay-off in works like Elektra or Fidelio, than, say, Tosca. New Yorkers have long talked about the Met Orchestra as the best in the city, (Even Kurt Masur's enlightened efforts with the fractious New York Philharmonic failed to put this Kaffeeklatsch item to rest.), and Levine began early on to show them off in three annual concerts of non-operatic music in Carnegie Hall—not just to show them off, but to give them the challenge of a "pure" orchestral concert. Conversely, in bringing opera to Symphony Hall and Tanglewood, he is both honing and broadening the musical understanding of both the orchestra and their audience.

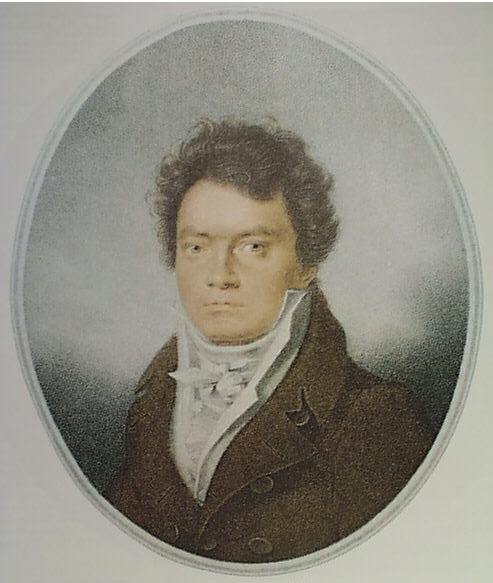

In Fidelio Maestro Levine had something even more ambitious in mind. It was part of his two-year cycle of music by Beethoven and Schoenberg; in fact it was the final work in the series, paired with Schoenberg's monumental opera, Moses und Aron, which was performed back in October—a work which can benefit from all the concentration and precision its performers can bring to it. (For that matter, performing it in the house is a challenge all its own. It didn't come to the Met until 1999, in nine performances followed by only three in 2003. Will Peter Gelb allow it back? Let's hope so.) Why pair Beethoven and Schoenberg? Levine explained, "Both composers experienced a certain amount of excited acceptance, but there were a lot of things that were neither understood nor accepted. So many things in late Beethoven didn't occur again until Schoenberg. When I did some of these programs with the Munich Philharmonic, people got into Schoenberg's music more easily—it sounded more accessible—and they were struck by how far Beethoven's music really went." With his splendid cast of singers and a Boston Symphony at the top of their form, Levine strove for a precisely defined interpretation which would realize Beethoven's concept in his final version of the work, the one routinely performed ever since its first great success in 1814. Did he succeed? Brilliantly, judging by the audiences adulatory rounds of applause for all concerned, above all, the magnificent Tanglewood Festival Chorus, South African tenor Johan Botha (Florestan), and American soprano Christine Brewer, who replaced an ailing Karita Mattila as Leonore. However, in spite of the consistency and forcefulness of Levine's interpretation, these very qualities reminded me that that there are other ways to look at the score as well, for example, most recently Colin Davis' quite different view, now available in a recording of his own highly acclaimed concert performances with the London Symphony at the Barbican in London last May, which I shall discuss in the second part of this double review.

Beethoven's demands on singers and orchestra invite concert performances, which bring his only opera into the more controlled and certainly more familiar environment, in which we have been comfortably hearing his symphonies for generations. (Remember, Levine wants to undermine this comfort.) A large part of the stock concepts which have attached themselves to this acknowledged masterpiece like pilot fish amounts to "Yes, Fidelio is unquestionably great, but it it flawed. Beethoven had little experience writing opera, he was a symphonist through and through, and the weaknesses of Fidelio prove it." Levine, according to his statement in the program notes, does not share this view, but in a way the very idea of a concert performance serves to perpetuate it. In search of musical perfection, we are giving up the creaky sets and the greasepaint which are an essential part of the development and character of this work. Beethoven was hired by a theater manager to write it. He took up an already well-used French libretto. It is not clear whether he or the management chose it, and he worked with a series of local translators and librettists, who made decisions about concision and dramatic effectiveness independently. Altogether, they produced two flops in 1805 and 1806, followed by a resounding success in 1814—in effect a resurrection of a work Beethoven had abandoned as hopeless. Whatever the difficulties, inconsistencies, or downright eccentricities of Fidelio, they were produced in a theatrical environment, by an enthusiastic and ambitious, if inexperienced composer, working with seasoned men of the theater of varying talent, not always harmoniously, not to mention the Viennese audience (for the 1805 performances entirely absent from the city because of the French occupation!), and the censor.

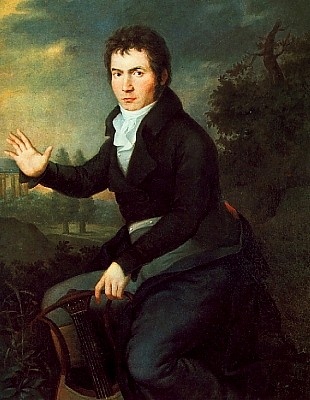

Beethoven first came to write his only opera during a period when Vienna was seized by a passion for French opera. In fact his interest in opera was first stimulated by a production of Cherubini's Lodoïska at Emanuel Schikaneder's (remembered largely as the producer and librettist of Mozart's Die Zauberflöte) new, state-of-the-art Theater an der Wien in March 1802. This was the first major French post-Revolutionary opera to be performed in Vienna, and it made a powerful impression, both on the public and on Beethoven. After that Beethoven always held Cherubini in special regard as the greatest opera composer of the time. Early the following year Schikaneder hired Beethoven to write an opera, but the libretto he gave him was a hopelessly old-fashioned heroic story set in ancient Rome, Vestas Feuer, which failed to inspire the composer. Beethoven was released from his contract in February 1804, when Schikaneder sold his new theater, but by then he was already at work on the material which became Fidelio. He was collaborating with Joseph Sonnleithner on an adaptation of a French opéra comique in the newly fashionable style, Léonore, ou L'amour conjugale by J.-N. Bouilly. With music by Pierre Gaveaux it had been first performed in early 1798 at the notoriously royalist Théatre Feydeau in Paris. Advertising it as a "fait historique," Bouilly claimed to have played a part in the story as a public official during the Reign of Terror, when he freed an unjustly imprisoned nobleman at the behest of his wife. Otherwise, like Lodoïska, it incorporated the most exciting motifs of French "Revolutionary opera," or "rescue opera," as it has been called. While the conventions of the genre celebrated the freedom of man, the story itself emerged from the Thermidorean reaction to the French Revolution and the Reign of Terror which followed.

There is no reason to think that Beethoven, who falsely pretended noble descent and whose political views tended to follow those of his noble patrons, sympathized with the values of the Revolution, however crucial the ideas of liberté and fraternité may have become for him. The ideals of liberty and social justice which resonate so powerfully in Fidelio and in "rescue opera" in general flourished without any partisan connection. In his negotiations with the censor Sonnleithner was able to assert that the empress herself "found the original very beautiful and found that no opera subject had given her so much pleasure." Nonetheless later generations have found a political strain in Fidelio, and this has enriched stage productions like Ewald Dülberg's famous left-wing version at the Kroll Opera in Berlin of 1927. When audiences associate the open-air cages in Deborah Warner's recent, widely-acclaimed Glyndebourne productions with the most egregious contemporary example of unjust imprisonment, it is moot whether this is to be considered political, or merely an updated visualization of the more general ideals which made their way into Fidelio in the aftermath of the French Revolution, equally valid for right and left. At the 1805 premiere of the first version, the audience consisted primarily of occupying French officers, among whom Fidelio was most definitely not well received. These sorts of theatrical associations are what is most obviously missing in a concert performance.

On the other hand, as members of a concert audience we are free to be open to Beethoven's values—above all Beethoven the artist's. In last week's performance of Fidelio, I believe, only each individual who was present could tell you whether they felt themselves in touch with these ideals, or whether they heard an intelligently conceived and magnificently executed performance of Beethoven's music. The experience was powerful either way.

Levine's conception of Fidelio is not vastly dissimilar to many which have come before. The many cuts and adjustments carried out by Beethoven and his librettists over almost a decade were all in the interest of concision and keeping the action moving ahead. Not that the original 1805 version was a very long opera. Critics and the public objected to the length of Beethoven's orchestral interludes and his tendency to repeat individual phrases of text, and the 1814 version is a masterpiece of concision, which also allows the crucial recognition scene in the dungeon, which is almost static, to carry its maximum effect. Most conductors respond to the forward impetus set by the overture (the last of four different attempts), letting up only for the marvelous prisoner's choruses which frame the finale of the first act. Levine adopts this with an almost self-conscious intellectuality. Beginning with the overture the fast passages were about as fast as I've ever heard them, contrasting with monumentally deliberate slower passages. Levine's overall concept is built of these contrasts, suggesting perhaps the duality of light and darkness on which the entire work is built, beginning with the domestic scene in the prison courtyard, leading down into Florestan's cell, and back into the light at the conclusion. The effectiveness of Levine's rapid tempi depends entirely on the quality of the execution by the orchestra and singers, and fortunately the Boston Symphony, the Tanglewood Festival Chorus, and every singer in what was pretty much a dream cast were in top form. I noticed only slight strain among the soloists in the faster ensembles, while in the solo passages, Levine observed his usual sensitivity towards the singers in allowing them plenty of flexibility in tempo and phrasing, compensating fully for Beethoven's devilish vocal writing. The orchestral textures were rich, brilliant, and clear, although I heard no surprises emerging from the inner voices. If anyone were looking for incontrovertible evidence of the progress the BSO has made under Levine, this is it.

It was a particular pleasure to see and hear three of the superb singers who made Die Meistersinger such a memorable event at the Metropolitan Opera only a week before, all in very different roles. Matthew Polenzani used his attractive voice and his gift for characterization to splendid effect as Jaquino, Marzelline's nagging ex-boyfriend. James Morris, who scaled one of the peaks of the operatic repertory in Sachs brought humanity and a vivid presence to the brief but key role of Don Fernando, the royal minister who sets Florestan and his fellow prisoners free. Johan Botha, who proved himself one of the great Walther von Stolzings the week before, proved himself also a great Florestan at Symphony Hall. In the first note of "Gott! Welch Dunkel hier!" I have never heard the like of his soft attack and gradual crescendo, building to a tremendous, almost super-human sound. This brutal phrase and the challenges which follow are Florestan's first entry in the opera, and we almost always hear some roughness in the first phrases, but not here. Botha's vocal control was perfect, and his interpretation nuanced and heroic. The fine English bass, Robert Lloyd, gave us a beautifully sung and sharply characterized Rocco. His neat phrasing was all the more impressive, given the lively tempi adopted for his first numbers, particularly the Gold Aria. As the villainous Don Pizarro German bass-baritone Albert Bohmen excelled, negotiating break-neck tempi in "Ha! Welch ein Augenblick!" and projecting all the domineering arrogance of command one could ask for. The Scottish soprano Lisa Milne has already attracted much attention with her Marzelline in the Glyndebourne production mentioned above. Here she brought to the role not only her splendid warm voice, but a humane characterization, and made herself especially valuable in her important parts in the first act quartet, "Mir is so wunderbar" and in other ensembles. It was especially gratifying to hear Christine Brewer's Leonore, a part in which she excelled in Sir Colin Davis' Fidelio. Her voice is large and silver in tone, showing a unique balance of lower and upper resonances, but as ample as her voice is, she is not really approaching the role as a Wagnerian soprano like Flagstad or Nilsson. She not only thrilled us in her great set pieces, but she also wove herself intelligently into the ensembles. As an actress, she is able to identify completely with Leonore's monumental outrage in "Abscheulicher! Wo eilst Du hin?" and, at the other end of the emotional scale, she projects most movingly Leonore's love and sympathy for her husband. Like Mr. Botha, Ms. Brewer is among the very finest living exponents of her role. William Hite and especially Robert Honeysucker delivered their small parts most effectively. Boston Symphony opera performances are always notable for the superb choral work of the Tanglewood Festival Chorus under John Oliver's direction, and in Fidelio, in an exceptionally populous deployment, they were at the absolute top of their form. Their expressiveness, agility, handsome sound, and clarity in complex tutti were exceptional, most unforgettably in the huge fff of the final chorus. Needless to say this incredible shout in celebration of wifely fidelity and human freedom brought the audience to their feet in loud and lengthy applause. This Fidelio was without a doubt one of the great moments in BSO history.

In general Levine's straightforward approach based on contrasts of dynamics and tempo is justified, since it is sympathetic to the idealism that wins out in the end. Beethoven's unique approach to opera is based on the human ideal in a way Mozart's and Wagner's never were. Dramatically problematic, this Weltanschauung which served Beethoven so well in his symphonies and the Missa Solemnis caused him a decade of toil and frustration, before his opera, Bouilly's true story, and the dramatic genre to which it belonged—"Revolutionary opera" or "rescue opera"—found a place in the classic repertory. In the first place, Fidelio is about conjugal love, loyalty, and courage, as Bouilly's subtitle and the quotation from Schiller's "Ode to Joy" in the final chorus show:

Wer ein holdes Weib errungen

stimm' mit uns in Jubel ein.

However, the celebration of human liberty in which this ideal concept is set, is not without its political resonances. Paul Robinson in his penetrating essay, "Fidelio and the French Revolution" [Cambridge Opera Journal, Vol. 3, No. 1 (Mar., 1991), pp. 23-48, reprinted in Paul Robinson, Ludwig van Beethoven, Fidelio, Cambridge, 1996, pp. 68-100] concludes somewhat tentatively that Fidelio is a symbolical representation, or metaphor, of the French Revolution, which in fact began with the storming of the Bastille and the liberation of the prisoners within it. He points out that the dramatic pause, silence, and ensuing trumpet call in the second act constitute a break in time, a hiatus, a historical revolution, after which the forces guiding human action and human relationships have changed. The all-too-human motivations of people like Jaquino, Rocco, and Pizarro, not longer obtain, and the higher thinking, feeling, and willing of Leonore and Don Fernando, as free agents, take their place. Whatever the attitudes of Bouilly or Beethoven to the French Revolution, they have celebrated its most ideal aspects on a moral plane. I can understand Robinson's discomfort with concepts like "metaphor" or "symbol." In history certain events leave their mark on the centuries which follow, for example the teaching and Passion of Christ, the Renaissance, or, in the present time, the conflict and devastation of the twentieth century. These events for better or worse transcend their historical realities and enjoy an after-life as ideal paradigms within human thought and behavior. While we may analyze the French Revolution and extrapolate any variety of interpretations of its events, protagonists, and their ideas, Beethoven has captured it on an ideal level in Fidelio, and when we go to the theater to experience it, we are able to come into contact with this ideal revolution, which even Beethoven was only able to conceive through his music.