The Awakening of Henry Schwartz

Gallery NAGA to Exhibit the Artist's Last Paintings

By: Charles Giuliano - Jan 26, 2008

In 1990 Henry Schwartz was given a retrospective of 81 works spanning a forty year period by the Fuller Museum of Art in Brockton, Massachusetts. It occurred during a time when museum retrospectives by living Boston artists were rare. They still are. So it was an occasion of remarkable significance.

It is common for artists following such a major event to suffer from what is described as "post project blues." But in the case of Schwartz, who is now 80, it went far deeper than that. Instead of a moment of triumph, noting the peak of a still promising career, the personal and psychological impact of the retrospective proved to be catastrophic. For the next year he continued to be productive but that tapered off in a seemingly untreatable depression.

For the next sixteen years his affairs were managed by his brother. His condo was sold and the studio emptied. The gallerist, Arthur Dion, of Gallery NAGA which has represented Schwartz for much of his career, was invited by the family to take anything from the studio that seemed fit for consignment. There were a handful of finished works, mostly rather small, which the artist had signed. But the mental health of the artist was so deteriorated that further exhibitions were out of the question.

Over the years of his illness Dion made regular visits to see Schwartz in a retirement home in Jamaica Plain. He appeared to be well cared for and the brother, who is now deceased, did a good job of managing the artist's assets which, in addition to the sale of the condo, included a pension from the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, and his social security check. His sister in law has also now passed away and care has been assumed by a niece who is a producer at WGBH a PBS affiliate.

During a recent conversation Dion discussed how those visits to Henry were routinely brief as the artist appreciated them but found them draining. About a year ago Dion recalls being shocked when Henry greeted him warmly, invited him to sit down, and was eager to catch up and communicate. For whatever reason, Schwartz conveyed that he had enough of being depressed. But, unlike the 1990 film "Awakenings," starring Robert de Niro, there is no such happy ending. While Henry appears to have snapped out of his depression his general health has deteriorated including breaking an elbow sustained in a fall. While he continued to draw over the past 16 years there is no plan to pursue painting.

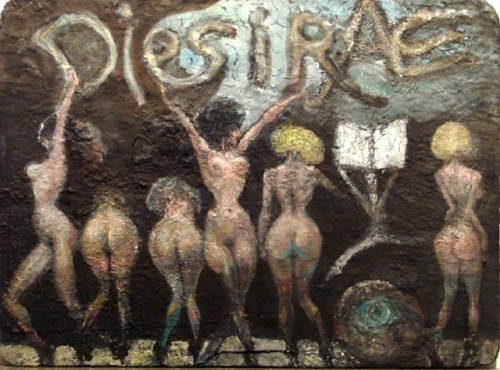

Having returned to a lucid state Dion requested and has received the artist's permission to show the suite of last works which have been in storage since 1991 when the studio was vacated. The gallery has an inventory of other works while much of the oeuvre has been sold to private collectors and been acquired by museums. Dion, some time back, sold a large and expensive work to the De Cordova Museum in Lincoln, Mass. "Vienna Blood: Dirty Dancing on the Danube, 1888-1938," 40 x 96," 1988. It is one of the artist's major works.

In preparing for the exhibition "Henry Schwartz: Boulevard of Broken Dreams, Approaching the Vanishing Point," from February 1 through 23 at Gallery Naga, 67 Newbury Street, Boston, 02116, transparencies of the works were shown to Schwartz. Dion reports that he recognized them but didn't recall painting them. He authorized the gallery to show the work but will not further participate in the project. Dion describes this event as "The most keenly anticipated presentation of 'historical' material in the gallery's 31-year history." To me he expressed that it is the "major Boston gallery event of the year."

While this is arguably true Boston Expressionism, a tradition of which Schwartz represents its second generation, has been a hard sell since its moment of glory in the Post WWII era, when many of its leading artists were represented by the important Boris Mirski Gallery. In the canon of modernism and contemporary art the leading Boston Expressionists- Jack Levine, Hyman Bloom (both living) and Karl Zerbe- have largely been dismissed as a regional phenomenon that bridged the gap between the Social Realism of the 1930s and the Post War "Triumph of American Painting" which focused on the emergence of Abstract Expressionism. Other than a handful of keepers of the flame, including the De Cordova Museum and Katherine French, the director of the Danforth Museum of Art, in Framingham, these artists have been swept up into the dustbin of history.

And yet the strain and influence of Boston Expressionism remains vivid and palpable among subsequent generations of Boston Painters. The influence of Schwartz as a teacher at the Museum School, from which he graduated as a prodigy in 1953, has been sustained in the work and teaching of Gerry Bergstein, among others, who states that "Henry was my most important teacher and a major influence in my work. I am far from alone as an artist who feels this way."

Having grown up in Boston the work of its expressionists have always been of special importance to me. Over the years I have seen most of their exhibitions including those at Boris Mirski and the Boston Arts Festivals as far back at the 1950s when I was a teenager. I recall being strongly influenced by the first Egon Schiele museum exhibition in America curated by Thomas Messer for the Institute of Contemporary Art when it was located on the Charles River in Brighton. At Brandeis University my art professors included the Social Realist, Mitchell Sipporin, and the Boston Expressionist, Arthur Polonsky, who is about to be shown by the Danforth Museum. I recall when Sipporin invited Levine to lecture to us. Later I got to know Jack intimately when David and Nancy Sutherland were making a documentary film about him. And I have spent time with the reticent and mystical Bloom.

In addition to this background I recall Henry vividly from his many Gallery NAGA exhibitions. He was always a huge presence, both physically, a truly enormous man, as well as in the power of the riveting work. In many ways we were not of the same world. Henry was deeply layered with a passion for the origins of Germanic music and the icons of Viennese history from Mahler to Freud. His works often conflated the style and distortions of expressionism, at its most extreme, with probing of history and deeply rooted iconography based on a vast knowledge of music. It was typical to encounter him with head phones connected to a small portable radio stuck in his pocket. The device was always tuned to classical music. Of course, today, Henry would be connected to an I Pod.

So I didn't always get it right when writing about his work and Henry rarely failed to correct my errors and lack of knowledge. Some of those now precious letters are stuffed into my bulging file cabinets. Probing through the folder as a part of preparing for this piece I found that wonderful drawing he did of me with the Pen and Sword that signify my profession and reputation as a critic. It is a pleasure once again to take up those instruments on his behalf.

While the current exhibition is indeed one of the year's significant events it will not be remembered as one of the great Schwartz occasions. The works are mostly small, but jewel like, and emotionally charged. But these are not the epic masterpieces which were presented at the Fuller Museum. This project offers a glimpse of the work with Henry's unique conflation of iconography, musicology and mordant, floozies with decrepit flesh. It provides an opportunity to reopen the case of the rise and fall of Boston Expressionism. Perhaps it will stimulate the curiosity of a younger generation of artists, critics and curators. So, for me, it is a bit odd to step back into the arena of this dialogue since it absorbed such a large chunk of my critical and aesthetic career. For me, Henry was and is a giant. In every sense. But, I fear, yet again, this falls on the tin ear of the art world. Henry, of course, is tuned to a different channel. Always has been.