Where Time Meets Space

James Crump's Troublmakers: The Story of Land Art

By: Nancy S Kempf - Jan 02, 2016

Troublemakers: The Story of Land Art

Featuring Germano Celant, Walter De Maria, Michael Heizer, Dennis Oppenheim, Robert Smithson, Nancy Holt, Vito Acconci, Virginia Dwan, Charles Ross, Paula Cooper, Willoughby Sharp, Pamela Sharp, Lawrence Weiner, Carl Andre, Gianfranco Gorgoni and Harald Szeemann. Running time 72 minutes. Summitridge Pictures and RSJC LLC Present a Film by James Crump. Produced by James Crump. Executive Producer Ronnie Sassoon. Producer Farley Ziegler. Producer Michel Comte. Edited by Nick Tamburri. Cinematography by Alex Themistocleous and Robert O’Haire. Sound Design Gary Gegan and Rick Ash. Written and Directed by James Crump.

“The present must go into the places where remote futures meet remote pasts.” ~~Robert Smithson, “The Sedimentation of the Mind: Earth Projects,” 1968

The raison d’etre of holy spaces from time immemorial – from caves to cathedrals, from stupas to mosques – is immersion in transcendent mystery. In a post-World War II secular age, Abstract Expressionists made paintings to afford something akin to this kind of experience. Mark Rothko told the painter Ethel K. Schwabacher he dreamt of having small chapels along the roads, where travelers could stop and commune with his paintings, “a kind of exalted rest stop somewhere between the drive-through and the motel” (Randy Kennedy. “In ‘Mark Rothko: From the Inside Out’ a Son Writes About His Father.” New York Times. Dec. 11, 2015). This is precisely what the art patrons John and Dominique de Menil made possible for Rothko in Houston, Texas, with the Rothko Chapel in 1971, the year after the painter’s death.

An even bolder perspective emerged in the late 1960s in a movement that would come to be known as Land Art, and the earthworks borne of its philosophical concerns are the most consummate manifestations of built spaces meant to mediate that same sacred end. Today, the idea of art as a vehicle of transcendent experience, as a creation the pilgrim enters seeking a heightened reality of expression and meaning, has become almost embarrassingly quaint.

Into our intellectually constricted era of cynicism and self-absorption comes a timely antidote in “Troublemakers: The Story of Land Art,” James Crump’s definitive documentary on the Land Art of Michael Heizer, Robert Smithson, Walter De Maria, Nancy Holt, and Dennis Oppenheim, opening January 8* at the IFC Center in New York City. For our world of narrow narcissism and trivialized themes, of excess that makes the Gilded Age pale, of the rejection of both science and philosophy (inquiry into questions of knowledge, truth, reason, reality, meaning, value), “Troublemakers” serves as a valuable reminder of a particular cohort of artists who were existentially committed to ideas and ideals greater than themselves

Unlike the ragtag, fragmented protest groups of today, e.g., Occupy Wall Street, cohesive movements characterized the zeitgeist of the ‘60s. The student, black power, anti-war, environmental, and civil, women’s and gay rights movements were confident and well-organized by comparison – and young artists, like their peers, felt empowered to confront the establishment. These artists saw themselves as real and powerful instruments of meaningful social change.

Civil enfranchisement, anti-war conviction, environmental stewardship – these issues raised moral concerns serious people of the time felt compelled to confront. In addition, this generation of artists came of age in the midst of another cultural phenomenon. NASA’s space program took us through a series of firsts that would change our perception of Earth. With Apollo 8’s 1968 photograph of an externalized orb and again in 1972 with Apollo 17’s iconic Blue Marble image, we saw our habitat as a deified object floating in the vastness of space.

Within this seismic shift of perception, intellectuals across the board were disgruntled with the status quo, among them visual artists fed up with the gallery system, and so they sought nothing short of the utter de-commodification of art production. These artists wanted to return art to a prehistoric, ritualized experience by moving out of the studio and the marketplace and back to Earth itself, guided by a philosophy that shaped the formal concerns of the work.

To that end, New York-based independent curator Willoughby Sharp and Liza Béar, an underground magazine editor who had moved to New York from London in 1968, founded Avalanche magazine and published 13 issues from 1970 to 1976. Avalanche eschewed critics, instead examining art from artists’ perspectives by relying almost exclusively on the interview format. In addition, Sharp wanted to de-emphasize New York as the center of the art world by focusing on European as well as American artists. Conceptual artists like Walter De Maria, Dennis Oppenheim, and Robert Smithson, who were beginning to venture into earthworks, were among the many artists Sharp promoted through the magazine.

No revolution, artistic or otherwise, occurs within a vacuum. If, in the nascent formation of their ideas, these artists envisioned creating on such a scale and in such novel ways as to reject galleries, they also relied on iconoclasts like Sharp and Béar, as well as gallerists, curators, and patrons of every stripe to recognize their vision and embrace the entrepreneurial courage to promote it.

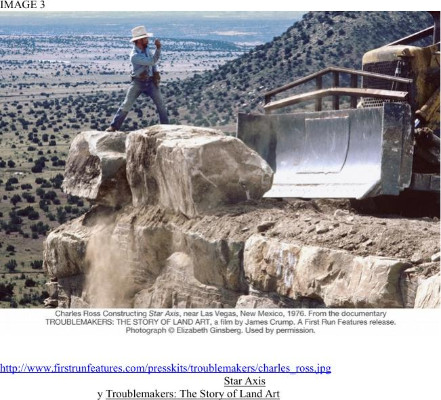

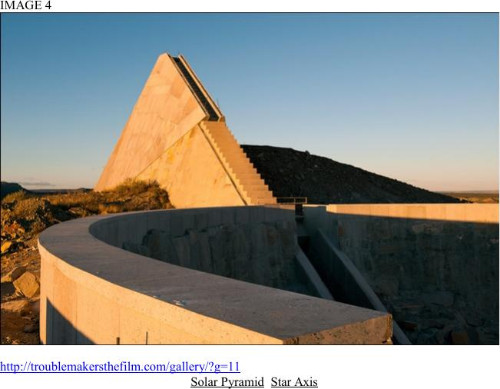

At one point in “Troublemakers,” sculptor Charles Ross relates the story of his search for a site for “Star Axis,” a naked eye observatory he has been in the process of constructing for over 40 years outside the village of Anton Chico in northeast New Mexico.

“When I finally decided these mesas were the places I really needed…, I had no idea how I was going to get it. …[A] cowboy came up over the side [of the mesa]…. We started chatting about the project, and he said, 'Oh, my dad would be interested in that. Why don't you give him a call?' and whipped a business card out. …. I called W. O. the next day, W. O. Culbertson, and gave him the short pitch. And W. O. said, 'Well, that sounds like just the sort of thing we need around here. How much land do you need?' …and I said, 'I need about a square mile.' And he said, 'Well, hell, we got plenty of those. Drive around the ranch and pick one out.’”

“Troublemakers” emphasizes throughout the centrality of gallerist Virginia Dwan to the Land Art movement. Dwan Gallery, Los Angeles (1959-1967) was identified with Minimalist and Conceptual Art. When Dwan Gallery, New York (1965-1971) opened, it became the first gallery to introduce Conceptual earthworks to a wider audience. When Smithson expressed the desire to work in open space, Dwan, along with Minimalist sculptor Carl Andre, accompanied him and his wife, the sculptor Nancy Holt, on trips to New Jersey, looking for potential sites. Dwan remembers, “We couldn't find land so I said, Well, let's have a gallery show.” “Earth Works” opened October 5, 1968, the first Land Art exhibition.

“Troublemakers” documents Dwan’s unflinching belief in projects unimaginable to most – in sheer vastness of scale and sometimes limitlessness of time to realize. Her generous patronage made some of the most profound Land Art projects realities, like Heizer’s “Double Negative,” Smithson’s “Spiral Jetty” and more recently in 1996, Ross’s solar spectrum environment for the Dwan Light Sanctuary in Montezuma, New Mexico, to name but a few. Her philanthropy continues to this day with her 2013 bequest of her collection and archive to the National Gallery of Art, of which “From Los Angeles to New York: The Dwan Gallery 1959-1971” is being curated by James Meyer to open in the newly renovated East Building in 2016.

Around the same time that Dwan mounted the “Earth Works” gallery show, Willoughby Sharp was inviting artists to exhibit in Ithaca, New York, in what would be the first American museum exhibition dedicated to Land Art. Sharp asked twelve artists, of which nine participated: Jan Dibbets of the Netherlands, Hans Haacke and Günther Uecker of Germany, Richard Long of Great Britain, David Medalla of the Philippines, and Neil Jenny, Robert Morris, Dennis Oppenheim, and Robert Smithson of the United States. Michael Heizer and Walter De Maria briefly exhibited but were not included in the catalogue (published a year later), and Carl Andre declined. “Earth Art” ran from February 11-March 16, 1969 at Cornell University’s White Museum of Art, along with site-specific installations around the campus. Andre notes in the film that, “It was a very prophetic show. It really was not so much work that had been done, but work that artists dreamed of. So it was a show, in a way, of artists’ dreams.”

Swiss curator and art historian Harald Szeemann’s 1969 Kunstahlle exhibition in Bern, “When Attitudes Become Form,” brought Land Art together with Conceptual and American Post-Minimalist Art and Italian Arte Povera. Along with Heizer, who used a wrecking ball to smash holes into the sidewalk outside, Richard Serra splashed lead in the foyer, Jan Dibbets excavated a corner to expose the Kunstahlle’s foundation, Lawrence Weiner removed plaster from a portion of wall, and Daniel Buren was arrested for pasting stripes around Bern. The Swiss were not amused.

Smithson, the most articulate exponent of the Land Art movement, provided a critical framework for Land Art in his 1968 essay, “The Sedimentation of the Mind: Earth Projects.” “Most critics,” he writes, “cannot endure the suspension of boundaries between what [Anton] Ehrenzweig calls ‘self and non-self.’…. The artist who is physically engulfed tries to give evidence of this experience through a limited (mapped) revision of the original unbounded state.” The desert “swallows up boundaries,” and it was to America’s vast desert spaces that Heizer, Smithson, and De Maria sought to see “through the consciousness of temporality.” When this happens, Smithson believed, the object “is changed into something that is nothing. This all-engulfing sense provides the mental ground for the object, so that it ceases being a mere object and becomes art. The object gets to be less and less but exists as something clearer. Every object, if it is art, is charged with the rush of time even though it is static….”

We hear Dennis Oppenheim recall his early ephemeral work cutting shapes into ice and snow and creating patterns with combine harvesters in wheat fields: “It was an art that took on the world. It took on real land. …. [W]e were dematerializing the object. We were basically reducing the one thing that we could sell to possibly a photograph only. …. This whole notion of sculpture as place and in gouging a line through the field to this sort of island, this pocket – one could imagine a sort of fantasy of timelessness.”

Heizer’s “Double Negative” (1969-1970) consists of two trenches cut into the eastern edge of the Mormon Mesa in the Moapa Valley in Nevada on a 60-acre site Dwan purchased for the project. The trenches line up across a large gap formed by the natural shape of the mesas’ edges. Including the open area across the gap, together the trenches measure 1,500 feet long by 50 feet deep by 30 feet wide. Heizer displaced 240,000 tons of rock in the construction of “Double Negative” that he then deposited in the natural canyon. The “double negative” of the title refers to the natural and to the man-made negative space – to absence, to what is not there.

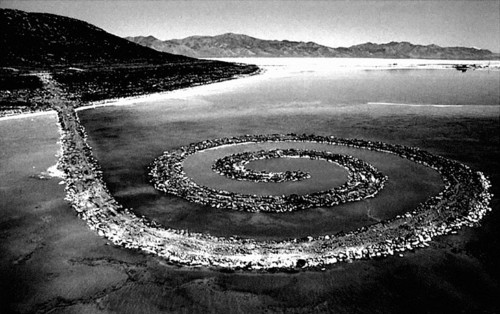

Smithson’s “Spiral Jetty” (1970) is located at Rozel Point peninsula on the northeastern shore of Great Salt Lake. Smithson constructed the 1,500-foot long by 15-foot wide counterclockwise spiral out of more than 6,000 tons of black basalt rock and earth from the site. How much, if any, of “Spiral Jetty” is visible on any given day, at any given time depends on natural water fluctuations. The Dwan Gallery, New York provided the initial funds for “Spiral Jetty.” After Smithson’s untimely death in 1973, three years after its completion, the Dia Art Foundation of New York funded the annual lease of the land surrounding the site.

In 1977, Dia commissioned De Maria’s “The Lightning Field.” Installed on a plateau in western New Mexico, the work is composed of 400 polished stainless steel poles – averaging approximately 20.5 feet high so that their uppermost points create a level plane regardless of the terrain into which they were planted – spaced 220 feet apart over a one-mile by one-kilometer grid. Though dramatic in an electrical storm, “The Lightning Field” does not depend on lightning. Rather it is meant to be experienced over any span of time – especially at sunrise and sunset – and visitors are encouraged to stay overnight.

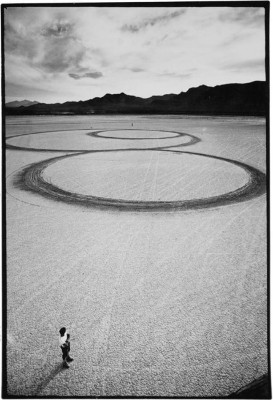

Much Land Art survives only as conceptual drawings, maquettes, and photographs, like Oppenheim’s “Time Line – Boundary between USA/Canada along St. John River; Fort Kent, Maine” (1968), which was an ephemeral one-foot by three-foot by three-mile cut between the two countries; De Maria’s “Mile Long Drawing” (1968), which was composed of two parallel chalk lines that temporarily extended for two miles across the Mojave Desert in California; and Heizer’s “Circular Surface” (late ‘60s-early ‘70s), which was a series of motorcycle drawings in the Nevada dry lakes.

On the other hand, Heizer has been reluctant to allow photographs of “Double Negative” to be exhibited, believing the work can only be experienced by one’s physical presence. Dwan donated “Double Negative” to the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles in 1984 with Heizer’s proviso that no attempt be made to conserve it.

There is, not surprisingly, a then-and-now nostalgia that permeates the reminiscences in “Troublemakers,” not so much for lost youth (we’ve all felt that) as for a world of intellectual and cultural engagement – for a time when ideas mattered and were debated in a spirit of camaraderie among a coterie that lusted for meaning. The quality of purpose these artists shared and their youthful seriousness is unambiguous. The earthworks they left us – a marriage of human creation and natural grandeur – tether us to the land and transport us into the awe and reverence and mystery of a pre-technological, pre-industrial, pre-agricultural sense of being in the world.

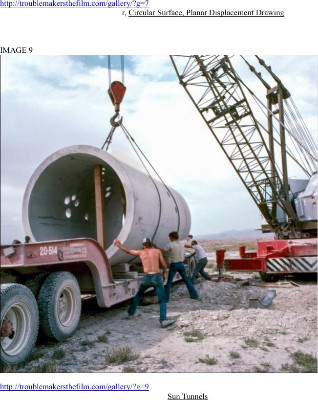

The last major earthwork Crump surveys in Troublemakers is Nancy Holt’s 2012 “Sun Tunnels.”

Comprised of four massive concrete tunnels, each eighteen feet long by nine feet in diameter, “Sun Tunnels” is laid out in the Great Basin Desert outside Lucin, Utah, in an open X configuration so as to align with the horizon at sunrise and sunset on the summer and winter solstices. In the top of each, holes form the constellations Draco, Perseus, Columba, and Capricorn. The tunnels, and the holes within them, frame the vast desert landscape and orient the visitor, and like all monumental Land Art, are meant to be experienced in duration.

We hear Holt explain that “[U]sing the sun, which is also a star, and…its light, the starlight, to shine through the star holes and cast a pattern of light on the bottom of the tunnels…[brings] the sky down to earth and [inverts] the sky in relationship, so that when you're walking in the middle of the day in the tunnels, you're walking on stars…

“Troublemakers” relies on a wide array of contemporary interviews and archival footage for commentary. If I have one complaint, it is that too often we are expected to remember a face or a voice without subsequent identification. Crump returns again and again to art historian and critic Germano Celant who, remarking on Holt’s “Sun Tunnels” says, “There is always this ancient connection between earth and sky, and the human body trying to fly, which is a god-like attitude…. All these artists represent the storyteller way of thinking from the ancient times until today….” The magnitude of the earthworks artists’ achievement – and the importance of their progeny like James Turrell and Andy Goldsworthy – is monumental and profound, and “Troublemakers” asks if a pilgrimage to Utah, Nevada, or New Mexico might constitute something like a modern-day hadj.

It would be my hope that “Troublemakers” encourages a new audience to engage in the natural environment with equal passion and veneration. In February 2014, Crump was shooting footage of “Double Negative.” He recalls, “At the top, on the edge of the work, you see nothing but horizon and the huge dome of the sky. You begin to sense this incredible vastness of space and your relative insignificance in this remote desert landscape. The energy of the site is palpable. It struck me as no less spiritual than any sacred mesa set aside for Native American rituals. When…we wrapped up the day’s work, it was like saying goodbye to a living, breathing entity.”

To momentarily return to Rothko, in “The Romantics Were Prompted” (1947), the Abstract Expressionist painter wrote, “Without monsters and gods, art cannot enact our drama: art’s most profound moments express this frustration. When they were abandoned as untenable superstitions, art sank into melancholy. …I do not believe that there was ever a question of being abstract or representational. It is really a matter of ending this silence and solitude, of breaching and stretching one’s arms again.”

Toward the close of “Troublemakers,” Michael Heizer takes credit for the Land Art movement: “Sure, I invented that idea.” Speaking today, Carl Andre responds to that notion with the necessary corrective: “No, no, no. Stonehenge was there before any of them, and the Indian Serpent Mounds….”