American Stories at LA County Museum

Paintings of Everyday Life, 1765 -1915

By: Charles Giuliano - Jan 03, 2010

American Stories: Paintings of Everyday Life, 1765-1915The Metropolitan Museum of Art

October 12, 2009 to January 24, 2010

The Los Angeles County Museum of Art

February 28 to May 23, 2010

Catalogue: Edited by H. Barbara Weinberg and Carrie Rebora Barratt

Essays by Carrie Rebora Barratt, Margaret C. Conrads. Bruce Robertson, and H. Barbara Weinberg. Published by the Metropolitan Museum of Art and Yale University Press,

222 Pages, 2009.

The magnificent exhibition "American Stories: Paintings of Everyday Life, 1765-1915" at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, through January 24, brings together iconic narrative and genre images of American art. Many of the works are readily familiar from text books and publications. But one would have to log daunting frequent flyer miles to track down and encounter many of these works from regional museums and historical societies as well as paintings from private collections.

If every picture tells a story then this survey from the Colonial era through the first year of World War One speaks volumes. Compared to the grand themes of European art of this time period, with references to religion, history, and classical literature American taste preferred a vernacular based narrative. The stories depicted in this stunning survey are generally accessible, often humorous, and achingly down to earth. The viewer required no education in iconography to relate to the subjects which were intended to please clients.

For the most part in American art of this time frame what you see is what you get.

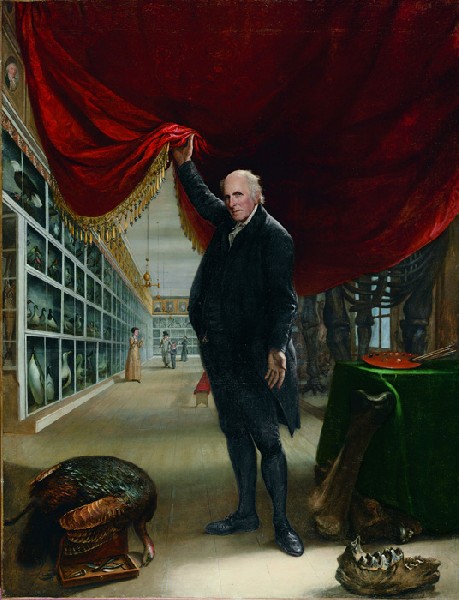

Although American patrons and collectors tended to be scarce and unsophisticated most of these artists managed to make a modest living. The more successful artists were often entreprenurial offering their work through lotteries, like the American Art Union, opening their own museums, like Charles Wilson Peale, or producing editions of prints. The artists of the Ash Can School, which bookends the exhibition, earned a living illustrating for newspapers and magazines. Even Winslow Homer worked as an illustrator and correspondent during the Civil War. And, from John Singleton Copley to John Singer Sargent, artists paid the rent painting portraits. Many struggled to get out from under the "Burden of portraiture."

Our first encounter with the exhibition at the end of October was so intense that we returned and devoted most of an afternoon to a second viewing in early December. Since then I have read chapters of the scholarly catalogue and lingered over the reproductions.

Having absorbed and deliberated such a broad overview of prime material there is the daunting challenge of sorting out such an insightful and visceral experience. It begs the perennial question in the field "What is American about American Art?" Asking that question has fallen out of favor. Through the efforts of emerging generations of scholars we have moved on from notions of self conscious regionalism and provincialism. Now it is likely that the best and brightest graduate students are as attracted to American studies as they are to European art.

Whenever we consider an American artist, period, or style, there is always the issue of drawing comparisons to European paradigms. That only changed when, as Serge Guilbaut proposed in a 1985 book "How New York Stole the Idea of Modern Art," the epicenter of the global avant-garde shifted from Paris to New York during World War Two. Today, of course, New York is but one of many global centers for the creation of advanced art.

Prior to WWII, however, if for example, you are considering the Colonial portraits of Benjamin West and John Singleton Copley one must do so within the context of comparisons to Sir Joshua Reynolds and Thomas Gainsborough. The style of both of these American artists changed radically when they pursued their craft for British patrons.

While Copley and West became more stylish through British influences it is a matter of taste, perhaps as much as jingoism, to prefer their plain and provincial American portraits. There is something more sober and compelling about those warts and all meticulous paintings by Copley which seem so superior to the flash and slash of the florid British brush. Devoid of mentors and influences Copley derived a highly finished version of realism.

Copley, a self taught prodigy, was so absorbed by the challenges of observation and reproduction that there was little room for style. Accordingly his work was redolent of substance. It is the very lack of fashion and taste that makes the work so strong and compelling. This speaks to the virtues of an American approach to home schooled art. In the beginning there were no academies and few masters to train under.

The message was often more important than the medium. There was a grass roots indigenous sensibility. It was "That Wilder Image" rooted in an American sublime based on nature rather than the romance of European ruins. It's what Thomas Cole depicted in the series "The Course of Empire." While not included in the Met survey they are on view at the New York Historical Society. Another important series "The Voyage of Life" is owned by the National Gallery. It would have been interesting to see Asher B. Durand's "Kindred Spirits," now in Arkansas, back in New York. It depicts Cole and the writer William Cullen Bryant standing on a rock overlooking Kaaterskill Clove while contemplating nature.

This exhibition includes two of the greatest works by Copley. The ambitious, grim "Watson and the Shark" set in the Havana, Cuba harbor. Copley created identical versions of the subject. The Met borrowed the National Gallery painting while the other is owned by the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. A second smaller, less spectacular Copley shown at the Met is the shirt sleeved patriot Paul Revere. He displays one of his tea pots and tools of the trade.

If the Copley portrait seems oddly familiar it was appropriated for the logo of Sam Adams beer. Copley also painted Sam Adams but the beer company conflated a younger Adams onto the famous pose of Copley's Revere portrait. We wonder what Copley might have thought about being ripped off in this manner. Or why, on his behalf, the MFA never sued the brewery.

The ambitious painting of Brook Watson, a smarmy man of questionable self interest and murky politics, conveyed to the artist how he lost his leg when attacked by a shark. Copley turned the tale into a sensational painting. It was actually painted in London shortly after Copley arrived there. Copley was viewed as an upstart when he displayed it privately and upstaged the annual exhibition of the Royal Academy. It got him both noticed and shunned by other artists.

The Watson painting conveys Copley's ambitions to be more than just a portrait painter. He took the composition from the Raphael Cartoons (for tapestries in the Sistine Chapel). The large scale works on paper mounted on canvas were owned by the royal family. It is likely that West got him in to see them. Copley appropriated from 'The Miraculous Draught of Fishes" for the group. He may have used the Apollo Belvedere on its side, which he studied in Rome, as the model for the figure of the nude swimmer Watson. Copley studied prints of Havana for details of the harbor.

The more diplomatic West, a Quaker from Philadelphia, was a friend of George III and the official History Painter to the King. It would have been appropriate to have included West's "The Death of Wolfe" (1770, The National Gallery of Canada). The painting includes a rendering of what Rousseau described as "The Noble Savage" as well as a half breed scout standing over him.

There are other significant omissions as well as curiously minor artists and works that have been included. It is a puzzle that there are no paintings by the eccentric but seminal, John Quidor, who illustrated stories by Washington Irving, or the visionary artists William Rimmer and Albert Pinkham Ryder.

The inclusion of tedious minor works such as William McGregor Paxton's "The Breakfast," 1911, is a curious embarrassment. We view the bored wife overcome by melancholy at the breakfast table while her husband is absorbed in a newspaper. The Irish maid is exiting the room with an item for the kitchen. It speaks volumes about proper but arid Brahmin marriages, a sad and tedious tale. The ennui of the ruling class and agita of the robber barons of the Gilded Age. Basta.

That sense of an American coldness and lack of passion is more poignantly conveyed in an absorbing painting by Thomas Eakins "Singing a Pathetic Song." With the emphasis on pathetic. Indeed. It reveals Eakins' ability to be crisp, precise, clinical in observation and yet distant and cold. He had the ability to drain the life out of a subject, brilliantly. His subjects and sitters overlap the novels of Henry James and Edith Wharton but with none of the compassion or affection for the characters. Eakins could be one cold dude. It is interesting to note that he is admired as one of the greatest masters today but was not very popular during his lifetime.

His greatest portraits "The Gross Clinic" (1875, Jefferson Medical College of Philadelphia) and the "Agnew Clinic" (1889, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia) were inspired by Rembrandt's "The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Tulp." The portraits which convey the artist's passionate interest in science, medicine, and anatomy were considered shocking and distasteful. They would have made great additions to this exhibition. .

The cool indifference with which Eakins and Homer depicted women compares vibrantly with their compelling views of manly and heroic life. Here we are shown one of Homer's most visceral scenes "The Gulf Stream," 1899. It depicts a demasted, small fishing boat with a single surviving black man surrounded by circling sharks. The blood in the water drew criticism of the artist for lacking proper taste. We see Eakins and his pals skinny dipping in " The Swimming Hole" (1883, The Fort Worth Art Museum). The varying poses of nude men may have been inspired by Michelanglo's lost cartoon for a never completed fresco "The Battle of Cascina."

The sexual orientation of Homer, a bachelor, and Eakins have been questioned. Both are most admired for their manly subjects. Ahem. While Trevor Fairbrother has "outed" John Singer Sargent. He is represented here by several of his more effete efforts which have the curious impact of making him appear to be minor when compared to the better represented Mary Cassatt. Of course, this would have been rather different had the Met managed to borrow Sargent's masterpiece "The Daughters of Edward D. Boit" from the Museum of Fine Arts.

Since this exhibition on so many levels is definitive it is perhaps arch to quibble. Often curators are not able to secure their wish list of paintings. There is the usual quid pro quo of borrowing great pictures. Often they are not available because of high demand or commitment to other projects. It is a testament to the clout of the Met that it succeeded in rounding up so many masterpieces. On the other hand, however great, they are, after all, just American paintings.

In an appeal to the general public this Met exhibition offers a generous sample of works by Homer including the beloved "Breezing Up (A Fair Wind)," 1873-76, and the charming "Snap the Whip," 1872. The Met's "The Veteran in a New Field" 1865, speaks volumes on the aftermath of the Civil War but this will not be apparent to the average viewer. There is also a truly great Eakins "The Champion Single Sculls (Max Schmitt in a Single Scull)," 1871, also from the Met.

It was truly thrilling to walk through gallery after gallery discovering so many ionic masterpieces. What fun to finally see John Greenwood's rollicking "Sea Captains Carousing in Surinam," 1752-58. What a hoot to see the artist barfing in the corner.. This saves me a trip to Saint Louis. Or, to the Maryland Historical Society for Charles Wilson Peale's seminal "The Exhumation of the Mastodon," 1805-08. We viewed William Sidney Mount's compelling "Eel Spearing at Setauket," 1845, in Cooperstown a couple of summers ago. But it was great to see it again. What a picture. This exhibition also includes his magnificent "The Power of Music," 1847, from Cleveland.

Also from Saint Louis there is the riveting statement on mid 19th century politics "The County Election," 1852, by the Mid Western master of genre, George Caleb Bingham. Well, there's another reason to book a flight to Saint Louis. The Met is showing its own great Bingham the sublime "Fur Traders Descending the Missouri," 1845. There are other great works by Bingham including Brooklyn's "Shooting for the Beef" and from the Manoogian Collection his seminal "The Jolly Flatboatmen," 1846. This latter painting makes one think of Mark Twain and his tales of the Mississippi.

This exhibition offers the incentive to compare and contrast the greatest American masters as well as consider the rather minor ones like John George Brown, Thomas Wilmer Dewing, Charles Cromwell Ingham, or Seymour Joseph Guy. We would have enjoyed more than a single work by David Gilmour Blythe. We appreciated seeing his work in depth at the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh.

The incentive of an ambitious project such as this is an invitation to separate the wheat from the chaff. Stocking too many galleries with so much chaff had a numbing impact. This would be a stronger and more compelling project had it been edited by a third.

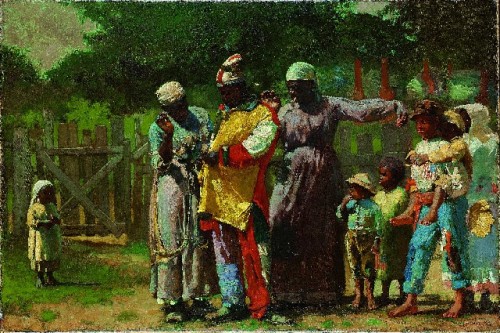

But there is also the serendipity of finding that occasional minor but fascinating painting for reasons more than pure aesthetics. It was a treat to seeChristian Friedrich Mayr's "Kitchen Ball at White Sulphur Springs, Virginia," 1838, from the North Carolina Museum of Art. It is a rare view of household slaves celebrating. We were inspired to draw comparisons to the Eastman Johnson's masterpiece from the New York Historical Society "Negro Life in the South," 1859. In this painting the lady of the house is visiting the slave quarters where she finds lovers courting and a man playing the banjo.

Through these subtexts the exhibition, in addition to providing master paintings, also invites us to probe questions about American vernacular culture. It evokes thoughts about social and political issues, as well as, the legacy of slavery and the American genocide.

These daunting and compelling issues emerge on the periphery of this exhibition.. It would have been a very different project to use paintings to explore slavery, the genocide of Native Americans, and the struggles of immigration during the era of the Know Nothing Party. That narrative was captured well in the Scorsese film "Gangs of New York."

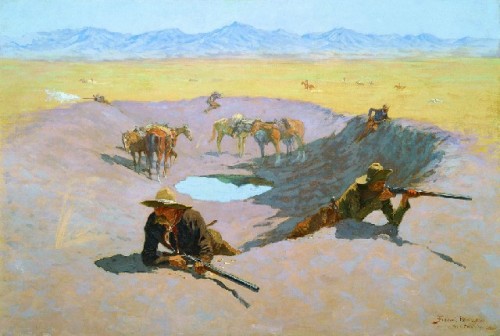

Just for chuckles it would have been interesting to see "Death of Jane McCrea," 1804, by John Vanderlyn. It is a pot boiler about a white woman captured and murdered by Indians. That would have conflated nicely with examples of George Catlin's paintings of Native Americans. Catlin is mentioned in the catalogue but not included in the exhibition. Instead, we view the John Wayne of American art Frederick Remington's "Fight for the Watering Hole," 1903, from Houston. And another image of Manifest Destiny, Charles Schreyvogel's "My Bunkie," 1899, from the Met. I'm curious, does the Met own a Catlin?

This survey does not include a single work by an African American painter. An obvious omission is Henry Osawa Tanner's 1893 "The Banjo Lesson" from the Hampton University Museum, in Virginia. There were surely a number of possible loans of a significant work by this artist. Perhaps an early work by Horace Pippin (1888-1946) might have been included.

The sense is that the Met strove to present a truly great overview of American art. It surely assembled many of the greatest works. But then pulled back from digging too deeply into how the art conveys the complex and often horrific history of our nation. So this is an intriguing but sanitized version of that narrative. It is rated PG except for those marvelous shark pictures.

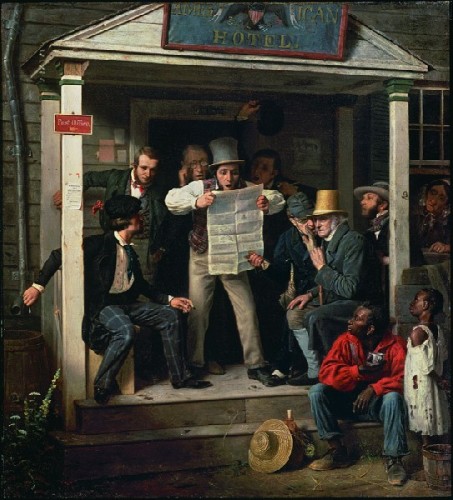

We are, however, truly grateful to encounter such gems as Richard Caton Woodville's "War News from Mexico," 1848. The painting was borrowed from the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas. We don't expect to visit there anytime soon. (See the comment posted below.) But it also underscores the numerous hidden treasures of provincial American museums.

Come Spring it will be a mandate to pursue when we take another month long drive exploring the heart and soul of America. This powerful and provocative Met show has surely whet our appetite.