Kiefer at Gagosian

What About Mass MoCA

By: Charles Giuliano - Jan 03, 2011

During December we visited the Gagosian Gallery in Chelsea during the final day of an exhibition of work by the foremost contemporary German artist, Anselm Kiefer.

It was a large, sprawling, messy installation with a maze of tall, vertical, lead lined vitrines containing decaying, mordant sculptures combining lead, brambles, antique tattered clothing, often for children and dolls. The imagery of the sculptures evoked submarines, bathtubs, or versions of Jacob’s Ladder. Frequently a line of text was hand written on the walls of the container.

In addition to the warren of vitrines were epic scaled, grisaille paintings with rough, textured, scratchy surfaces. The images ranged from Alpine landscapes to enormous signifiers like a bird/ hawk with a vast wingspan.

The gallery was mobbed with visitors on a day when the majority of shows that we viewed were sparsely attended.

The mood of the people seemed somber, attentive and relatively subdued.

The work with its decades long reflection on the aftermath of the Third Reich and its imagery of decay and scorched earth evokes respect and reflection more than pleasure and adulation. We attend Kiefer exhibitions with a sense of obligation. It seems to be a duty and responsibility to absorb the work and its implications of the horrific and Dionysian sublime. Surely there is never any joy or pleasure in the experience.

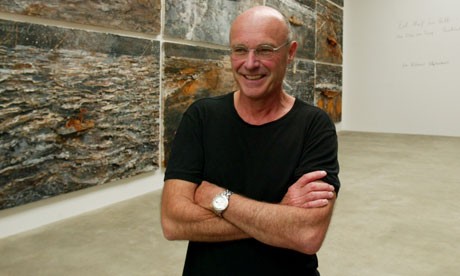

Not surprisingly, although Kiefer is one of the most renowned artists of his generation, he is reclusive and intensely private. He lives in an environment of the work which is epic in scale and prolific. It is said that it took 110 moving vans to transport the work to a new studio outside of Paris.

So there is something mythic about the artist, his monk like hibernation and frenetic production. Is it a life of creation or penance? Growing up in post war Germany (born 1945) he appears to have devoted a life to an exorcism of the era of his parents. It is a burden and theme that is reflected in the work of many artists and filmmakers of his generation. It is what charges and makes of German art and culture a genre that is notable for its gravitas and insight.

Starting with Joseph Beuys, who actually served in the Luftwaffe and was shot down in the Crimea, post war German art has been complex and compelling. Kiefer absorbed a lot from study with Beuys. Particularly his development of social sculpture and actions. This was particularly true in the early work of Kiefer in which he photographed himself delivering the reviled Nazi salute. It caused many to question his motive. It has often been difficult in the work to discern whether Kiefer despises or celebrates the Nazi aesthetic. The critical dialogue remains murky.

Perhaps the conundrum is attractive to viewers. We look to the work hoping for insights and answers. Just why has he used lead? It is a material that is easy, soft and pliable to handle, but also weighty, lacking in structural integrity, and deadly if not handled carefully. It is quick to decay and morph into self destruction. Hence, a most desirable material for the pervasive metaphor of the work. Its sense of decay and impermanence.

It is an issue that causes fits for collectors, conservators and museums. Just how to treat, display and preserve works that have staggering value? By the very nature of their materials and techniques of creation they are anticipated to deteriorate. It is, of course, a most apt metaphor for the artist’s post apocalyptic vision.

We have progressed to an understanding in contemporary art that preserving the pristine state of art, as it emerges from the studio, is not a pragmatic concern. The work is allowed to have a life of its own.

Will there be an outcry, centuries hence, when a museum employs state of the art techniques to restore works by Kiefer to their original condition? Imagine debates along the lines of those that followed the cleaning and restoration of Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel ceiling frescoes. Perhaps some scholars will argue that rubble best represents the artist’s intention. The work has simply evolved to its natural entropy.

With so much work of great value the question becomes where to put it. There is little space to display examples in private collections. Particularly, if the collectors acquire a number of pieces. Even museums are limited in how many works may be displayed.

Not surprisingly we have heard discussions of creating a long term Kiefer installation at Mass MoCA. One large space was given over to a number of paintings and sculptures but that has now ended. There has been speculation that the museum is negotiating to create another building, like its Sol LeWitt, 25-year-long exhibition.

The success of the LeWitt project has created considerable interest in similar projects dedicated to either single artists, like Kiefer, or collections in storage. There is now a kind of endgame. Even vast Mass MoCA has a limited number of vacant factory buildings. It must be ever more selective of how best to use its remaining space. What at first seemed vast is becoming more finite.

Taking on such expanded exhibition space also means a commensurate increase of staff and expense. Particularly, if there are complex climate control and conservation concerns over decades. The LeWitt installations, in that sense, are low maintenance. If necessary they can be restored and even repainted. Also, the MoCA project with LeWitt is partnered with the Yale University Art Museum which largely endowed it. Yale “owns” the plans and drawings for the designs that were executed.

While complex, it is anticipated that MoCA will negotiate similar endowments for long term exhibitions. For now it appears that there are a number of takers. But also a mandate to make decisions about work that will hold interest and attract visitors for coming generations.

When I asked Mass MoCA Executive Director Joe Thompson about speculation regarding a Kiefer building he would neither confirm nor deny ongoing negotiations. I suggested the Connecticut collection that previously had loaned work. Obliquely, he responded that if it happens Kiefer would extend beyond a single collection to include "a number of works."

The next move appears to be up to Mass MoCA.