Abstract Expressionist New York

MoMA to April 25 Then AGO May 28 to Sept. 4

By: Charles Giuliano - Jan 05, 2011

The title of Irving Sandler’s 1982 book was “The Triumph of American Painting: A History of Abstract Expressionism.” In 1983, Serge Guilbaut published “How New York Stole the Idea of Modern Art: Abstract Expressionism, Freedom, and the Cold War.”

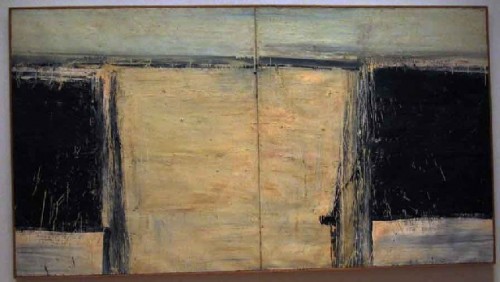

The key words “triumph” and “stole” put an aggressive and combative spin on the generation of artists presented in the sprawling installation “Abstract Expressionist New York” on view at the Museum of Modern Art through April 25. A selection of 100 of the 250 works, primarily the paintings, will make one stop, to the Art Gallery of Ontario, in Toronto, from May 28 to September 4.

During an interview with Sandler, I asked about ”Triumph.” He responded that it was not his idea and that the provocative title was used by the publisher to sell books. Hmm.

For this intensive view of its holdings, MoMA cleared its fourth floor permanent collection galleries. Since the project focused entirely on the collection of the museum, it is and is not to be regarded as a ‘special exhibition.’

It is precisely the flash point that opened the museum to a range of adulatory but also mixed and even harsh critical responses. While the major artists of the era are presented in depth, there is considerable speculation and second guessing about peripheral members of the New York School, particularly the handful of women artists, mostly represented by a single work.

Even the first tier artists, who are shown in depth, it is argued, might have been better represented by loans from museums, most notably, the Whitney and Met, which are within walking distance of MoMA. Clifford Still, for example, is better represented in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which also owns the Pollock masterpiece ”Autumn Rhythm.”

So, as often appears to be the case in any effort to explore Abstract Expressionism, the MoMA project may be viewed as self serving, chauvinistic, smug, and reeking of aesthetic testosterone.

Oh well. What a great show or whatever you want to call it.

During a pre Holiday week in New York I set aside most of a day to this seminal MoMA exhibition.

Not that it was a surprise or even a revelation. Most of the experience entailed hanging out with old friends. In this case, however, in great depth and critical mass. The primary special interest lay in the cracks and seams. Those are the single examples of works by lesser known and women artists.

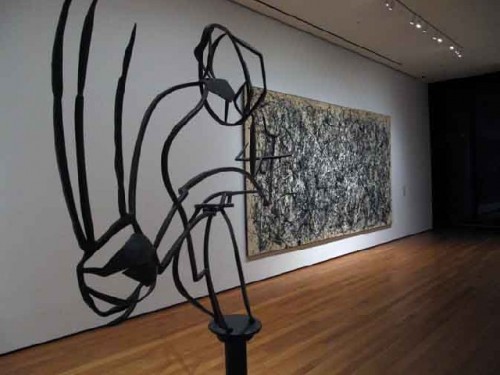

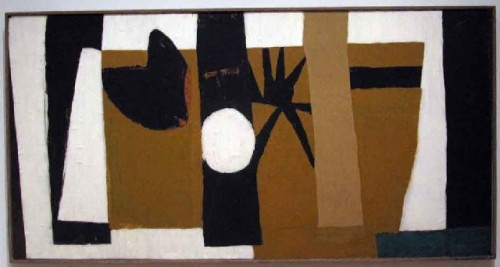

If the minor painters and women of the era were underrepresented this pales by comparison to the field of sculpture. David Smith was the only representative of three dimensional art in the New York School. The entire generation of sculptors were raped, kicked to the curb, and left for road kill. This project, clearly, was all about painting, with a smattering of photography and works on paper, as well as those few examples by Smith.

Perhaps, at some point, MoMA will correct this major lapse and organize an overview of works by Ibrahim Lassaw, David Slivka, Philip Pavia, Louise Nevelson, Peter Grippe, David Hare, Reuben Nakian, Peter D’Agostino, Richard Lippold, Seymour Lipton, Constantino Nivola, Theodore Roszak and others.

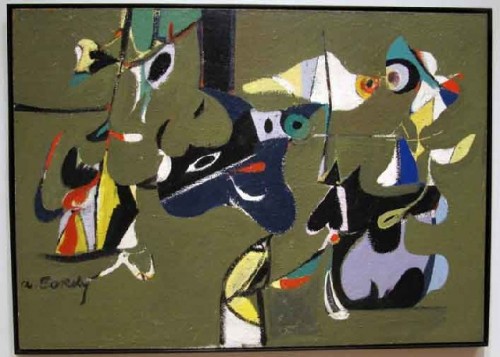

The combative approach to the generation of the New York School has its justifications. A number were immigrants- Willem deKooning, Mark Rothko, Arshile Gorky. They all struggled to survive during the Great Depression. Most if not all of them were on the dole of the WPA. Many were alcoholics. The drinking bouts and arguments at the Cedar Bar were legendary. Surely many were chauvinistic. There were notable suicides- Gorky by hanging, Rothko slit his veins (elbow), and a drunken Pollock slammed into a tree killing another passenger.

For the most part they were leftist and interested in surrealism, the subconscious, automatic, and psychoanalysis. All of this was discussed in the summer long exhibitions, and panel discussions, of the Provincetown Art Association in its seminal “Forum ’49.” It was organized by Weldon Kees and included many artists who came to the Lower Cape to study with Hans Hoffman. They followed his mantra of “Push-Pull.”

With all of its machismo, rough edges and chauvinism it was the art of The Great Generation. Those Americans who endured ten years of poverty, fought Fascism, believed in a simplistic Marxism, and were involved in the transition of the locus of the global art world from Paris to New York.

As Guibault states, in a much debated book, American artists were packaged by the State Department in the marketing of our democratic ideals as an aspect of the hegemony of our dominance as a social, economic and cultural force. There was a political and marketing impetus in the selling of Pollock and deKooning as the equals of Picasso and Matisse.

There was the Post War packaging of all things American from jazz and rock and roll, to Lucky Strikes, Coca Cola, Hollywood and blue jeans. This selling of America took place against the backdrop of McCarthyism and purity tests of our patriotic allegiance.

It is when Louis Armstrong released the album “Ambassador Satch” and Duke Ellington recorded his “Far East Suite.” Benny Goodman performed during the 1958 Brussels World Fair. Recall the famous 1959 “Kitchen Debate” between Vice President Richard Nixon and Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev in a display at the U.S. Embassy, Moscow, Soviet Union. American culture, as well as goods and services, as Guibault points out, were propaganda weapons during the Cold War.

It is arguable that without avant-garde European arts, culture and science there would have been no New York School. The Peggy Guggenheim gallery Art of This Century became a matrix between her French surrealist circle and young Americans. She was married to Max Ernst and the first patron of Jackson Pollock. She hosted and exhibited the Surrealists in Exile. They were dominated by Andre Breton who refused to learn English and created an elitist Parisian salon in Manhattan. For a time Gorky was a part of their orbit until he left in disgust.

Artists such as Matta and Andre Masson would have been a valuable and insightful addition to the MoMA show which opted to be hermetic. We also do not have the opportunity to consider the influential Mexican muralists David Alfaro Siqueiros, Diego Rivera, and Jose Clemente Orozco. Briefly, Pollock was an assistant to Siqueiros. Rivera painted the famous Rockefeller Center mural which was destroyed for depicting Lenin. And Orozco painted important American murals (Baker Library at Dartmouth College) which were widely influential. The scale of the works by Mexican artists was particularly influential in ending the paradigm of “easel painting” and led to the “all over” paintings of Pollock who worked on the floor of his studio.

Which brings us to the issue of how the MoMA survey functions as a learning experience. For the most part it is preaching to the choir. To anyone who has considered modern art these works are as readily familiar as Monet’s water lilies or the dancers of Degas. They are the mother’s milk of contemporary visual culture. Is there really anything new to be said about Abstract Expressionism? This project provides the physical evidence of what we already know. It represents no significant learning curve or impetus for a new and updated critical analysis.

The Triumph of Abstract Expressionism is so total and complete that we navigate the galleries with no resistance. There are few or any instances of being ambushed by the discovery of individual works, or juxtapositions of one master against another, that evoke heavy duty thinking and reordering of the paradigms. It is difficult to attack the purity and authority of the Great Generation that fought for Truth, Justice and the American Way.

The MoMA project conveys the subtext that this was, arguably, a movement of art when all of us could agree on its power and authority. Immediately after that the hegemony was shattered into so many subsets and arguments that art devolved into pluralism, feminism, post modernism, and multi culturalism. Today, each major artist is an island and movement onto his or her self. There is little or no cohesion, agreement, or continuity. There are no longer any isms.

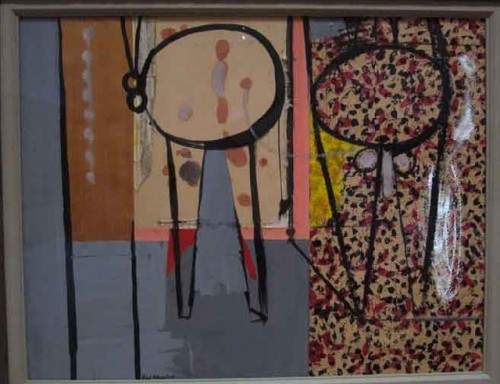

Perhaps what is most memorable and insightful about the MoMA project is its glimpses into the cracks of the second, third, and fourth tier of artists of the New York School and its women. This survey underscores that MoMA made only token acquisitions. Seemingly hedged its bets. Which is what is so clear and embarrassing about this overview of the collection. It enforces the notion that the curators were censoring and evaluating with their faint praise and minimal support for these artists.

We are asked to read into a single work and then compare and contrast to the multiple examples by major artists.

This was the first time, for example, that I viewed a painting by Hedda Sterne. She was born in 1910 and may still be alive. I could not find an obituary on line. Sterne is most notable for being the only woman in the famous group portrait of “The Irascibles” as they were dubbed by Life Magazine. I have always been curious about the work and this single painting accomplishes little in an understanding of her place in the history. Or even a clue as to why she was the only woman invited to pose with the boys. Where were Pollock’s wife, Lee Krasner, or deKooning’s wife, Elaine? Were they at Bloomingdales during the photo session? How did Sterne manage to sneak in?

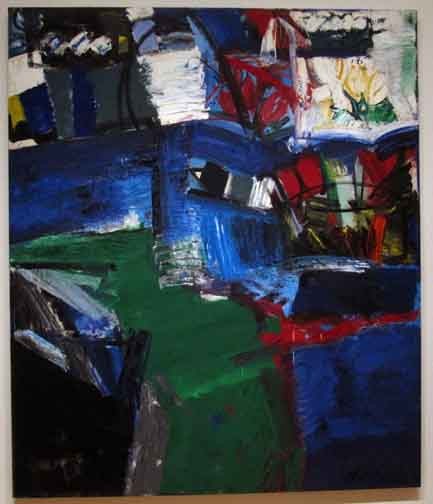

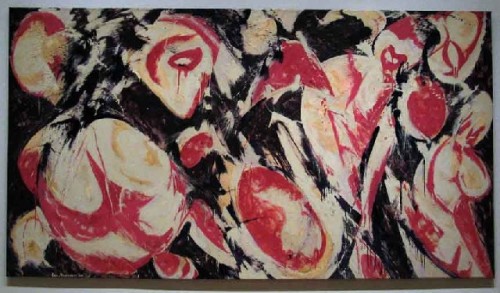

There are a few women in the MoMA show. Their paucity speaks volumes. Krasner, who has been the subject of intensive critical attention for decades, is represented by more than one work. There is also just a touch of Grace Hartigan and Joan Mitchell. Both are interesting and substantial artists who deserve better treatment. But I debate why Helen Frankenthaler has been included. It is not a good painting and her work belongs to the next generation of Formalism and Color Field Painting.

Similarly, it was curious to see a single work by Alfred Leslie. It dates to when he was a leader of the so called “Third Generation” of Abstract Expressionism. The label reveals that it was a part of the famous “999” fund established by Larry Aldrich. So named because the money for acquisitions of works by young artists did not exceed $999. It is how some of the first works by Frank Stella and others came to MoMA.

All of the early work of Leslie was destroyed in a loft/ studio fire in which several fire fighters lost their lives. After that Leslie was among the first avant-garde painters to return to the figure and realism.

Similarly, there are fleeting glimpses of works by Milton Resnick, James Brooks, Richard Pousette-Dart, William Baziotes, or Theodore Stamos to mention but a few. I do not recall seeing a work by Esteban Vicente. The single work by Stamos was interesting as he was an executor involved in the scandal of the Rothko Estate by Marlborough Gallery.

The term Abstract Expressionist as applied in this instance is a misnomer. It was first used to describe the work by Vasilly Kandinsky in the 1920s. It resurfaced as an umbrella term for a generation of New York/ Provincetown/ East Hampton artists. Because of the awkwardness of its one size fits all premise there is the more benign New York School.

In his competition with Clement Greenberg the critic Harold Rosenberg made a case for Action Painting. In essays Rosenberg wrote about American Type Painting and even Coonskinism. He made an analogy to American artists, in Coonskin hats, fighting a hit and run guerrilla war against the organized British troops. Again, it demonstrates how deeply entrenched is the notion of combat and conflict in the initial critical thinking about the Post War generation of American art.

Of course, art is not about winning. Today it is absurd to even think of New York winning and the School of Paris losing. There is even a witty painting by Mark Tansey that illustrates that fictional transition. A further absurdity entails noting and discussing the exact moment when New York lost its dominance as the center for visual art.

I recall an interview with Kathy Halbreich, then at MIT, when she conveyed that keeping up with contemporary art entailed visiting and thinking in terms of continents. It was the moment when biennials were cropping up all over the world. Critics and curators have been logging frequent flyer miles ever since in a frantic effort to keep up. All of which clearly decentralizes the dominance of New York.

Which may indeed be a motive of MoMA and this ambitious but flawed project that reminds us that, back in the day, for an all too brief moment in time, it was the epicenter of the international art world.

That was then and this is now.