Izhar Patkin's Space Time Continuum

The Wandering Veil at Mass MoCA

By: Charles Giuliano - Jan 19, 2014

At the top of the steps entering the vast space of Building Five of Mass MoCA, one of the grandest for contemporary art in North America, there is that crucial first impression in a series of annual one person exhibitions. For those familiar with the space and its history of seminal exhibitions this is known as "the approach."

A strength and weakness of visual art is its immediacy. It takes but a moment to absorb the work. Which is different from reading a book or attending a performance of music, theatre or cinema. There is a quickness unlike experiencing other forms of the arts and literature. Art is time sensitive. The sense of judgment may be instantaneous and often infallible. There is an immediacy of assessment of the potential to absorb and hold us.

The time and space we allow for the encounter is often a measure of its impact, importance and value. As we mature and change, absorbing decades of such experiences, this is a constantly shifting process.

For critics there is the challenge of getting it right the first time. There is no going back to adjust opinions over time. It is particularly difficult when encountering complex contemporary work by unfamiliar artists. Critics are first responders. Izhar Patkin has shown for decades but, other than a past Whitney Biennial, was unfamiliar to me. There is a formidable bibliography if one undertakes research.

There is risk taking on the part of Mass MoCA to present relatively unknown artists. Playing it safe, however, defeats the mandate of a unique institution. MoCA is notable for not being afraid to fail.

From the steps, looking out at a maze rooms of wall size paintings in ink on pleated illusion (tulle curtains), 14' x 22' x 28' each, there were mixed responses. Patkin and Pakistani poet, Agha Shahid Ali, started their collaboration on Veiled Threats in 1999. Each of Patkin’s veiled rooms corresponds to one of Shahid’s poems.

There were intervals or stations to be encountered before entering the maze with the requisite ball of psychic string.

Quite in our face at the entrance to the exhibition is the oddly proportioned, polychromed, aluminum sculpture of the stretched and just over life sized Don Quixote astride a slightly smaller horse. The steed is looking back at its akimbo rider archly contemplating himself in a hand held mirror.

For Don Quixote, as an ersatz knight, the notion of vanitas and self reflection were paramount to a mind set uniquely described as quixotic. His amusing side kick and squire, Sancho Panza, represented a reality check on his blundering, deranged misadventures. Patience and shuffle the cards.

This older piece in a retrospective of work from the past few decades sets up the trope of a series of narratives. The Spanish character is the ultimate signifier of an individual lost and delusional resulting from a misguided narrative process. Having read deeply into the preceding era of chivalry Don Quixote set out to replicate the heroic deeds from his beloved books.

In 1571 Miguel de Cervantes fought in the decisive Battle of Lepanto which defeated the Turkish navy. It spared Europe from the invasion and conversions of Jihad. He suffered three gunshot wounds; two in the chest, and another which rendered his left arm useless.

His great literary masterpiece focused on the comical last gasp of chivalry represents a shift from faith and idealism, from medieval to High Renaissance, into the artifice and cynicism of Mannerism. This led to the pragmatism and scientific methods of the Age of Reason. Even today astronomers and scientists are seeking the "God Element." Even the most rational among us refuse to believe that God is dead. Uniquely Patkin describes pursuing a secular narrative.

Given the pursuit of that secular narrative Patkin’s Don Quixote is totemic. In dialogues he describes himself as a modernist who evolved from Bauhaus Israel. For an extended period of time he dropped out of the market frenzy of post modernism. What sets him apart as an aberration is a reactionary insistence that his work is sincere and utterly lacking in de rigeur, chic, irony.

The Mass MoCA installation represents an obstacle course through a Steppenwolf encounter with a series of rooms. They represent narrative vignettes conflating to a whole, hopefully, more than the sum of its parts. That perception is up to the commitment of individual viewers. There is a lot of visual information to imbibe and digest.

There are stoppers before we move on to the exhibition's middle passage.

From 1985 is a freestanding wall constructed from recycled barn boards Before the Law Stands a Doorkeeper that has painted images. It serves as a gateway to the rest of the exhibition. We see elements in embryo that will later develop.

Behind that is an early curtain Maids of Honor (1987/88) based on the painting by Diego Velasquez. This densely folded, polychromed painting (ink on pleated neoprene) spreads out the source into a composition of its aspects. The masterpiece of the Spanish artist placed the viewer into the space of the painting. Like the King and Queen visiting the artist’s studio (seen in the mirror on the back wall) we are visitors/ intruders on the young princess and her various court attendants. The artist accomplished the impossible by transforming a commissioned portrait into one of the resonating works of Western Art. It is the most complex exploration of pictorial space in Western Art prior to the 1907 Les Demoiselles d’Avignon by Picasso.

As we enter the first of the veiled rooms there are conflicting responses. There is disappointment that the vast space has been subdivided. According to Sun Ra 'Space is the place.' We consider a denial of the container and its inherent beauty. Just what is the advantage of this Mass MoCA configuration when compared to galleries in a museum? The singular beauty of the space itself is neutralized by this installation. On the other hand the dimensions of the great hall made it possible to present the large scale works of an artist the museum believes in.

Once in the rooms there are a new set of options and considerations.

There is an immediate matter of the time we allot for the experience. How long does it take to “get” the work? Will longer contemplation yield a better and more satisfying result? When do we become satiated? Is there enough intrigue to compel us longer to linger.

Being a neighbor of the museum skews the decision making process. There will be ample opportunity and incentive over the coming year to revisit the exhibition. Perhaps months from now the Veils will begin to reveal their layered secrets. It’s one the great advantages of living next to a world class museum.

Critics vary in their approaches. Some spend a long time and take notes. They are catalogues and websites to refer to. Some critics attempt to explain the work.

That has never appealed to me. I try to convey responses that evoke and represent the work. We entice readers to form their own opinion.

The veiled rooms elicit a palpable sense of wonderment. We are daunted by the scale of the Veils and degree of difficulty in deciphering their gossamer ephemeral images. How does a flat graphic image perambulate over folded curtains or Veils? Do they evoke, as has been suggested, icons like Veronica’s Veil or the ersatz relic the Shroud of Turin? That notion is deflected by the artist’s stance as a non believer. Modulating his position as an atheist the work is inspired by collaboration with a Pakistani Muslim poet. Is there an element of religious orthodoxy in the poetry deflected by the artist’s lack of interest in the narratives of any single religion? How much do we read into his decision, as an Israeli, to collaborate with a Muslim poet? Only the artist can answer that question on which he declines to elaborate. The poet is deceased so it’s a dead end discussion.

Since the rooms are inspired by specific poems we wonder why they not integrated into the installation? Consider, for example, the possibility of laminated copies in the rooms for visitors to read and reference. There is an upcoming event in which the poems will be read. Might there be head phones for a self guided tour? If the poetry was so specific to the inspiration of the series why make it inaccessible? Was this a mutual decision reached by the artist and poet?

It was astonishing to learn how the Veils were made. The artist creates them by searching for images which are then processed through Photoshop. They are printed onto the folded material. One assumes that they are created flat and then hung in the pleated manner. The artist insists that is not possible. It took him more than 20 years to develop enormous printers adapted to 3-D surfaces.

Process and technology are important to his oeuvre. There is a room of abstract “carpets” in which paint has been forced through metal mesh. Technical impediments serve as a head wind giving the artist resistance and motivation to push against. The resultant problem solving is a part of his art practice.

We encounter sculptures in glass, ceramic and other materials. They serve as stations and diversions winding our way through the chambers of Veils. I’m not sure the sculptures stand alone.

The neo-Baroque, Palagonia, (1990, wax, gold leaf, wood, and mixed media, 52” x 108” x 72”) is rather a mess. We find it on the balcony above the far end of the gallery. It is a complex narrative but the cheesy surfaces are off-putting. The website text states that it is inspired by the Villa Palagonia in Sicily and Bernini’s Ectasy of Santa Theresa in Rome. The show consisted of both the multi-figure sculpture and its photo representations in an ethereal, spectral range of white on white. There are perforated photo details of the work on the wall behind. The panels do not significantly enhance our understanding or appreciation of the complex iconography of the sculpture. The overall impact is that of yet another tangent by the artist.

On the landings of the stairs leading to the gallery are monitors with video works. For a time the artist collaborated with the video master Nam June Paik. They met when showing together in a Whitney Biennial and shared the gallerist Holly Solomon.

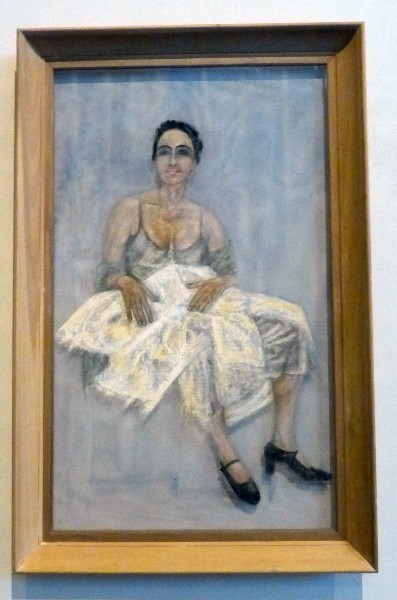

There are other non sequiturs. There is a pedestrian portrait of a woman seated with a white blanket over her lap and the profile portrait of a man. There is an enervating seated nude woman in porcelain.

Retrospectives by mid career artists represent an end and beginning. Yet again Mass MoCA has presented work that leaves us with a lot to think about. We anticipate further encounters with Patkin’s work.

Dialogue between Patkin and David Ross