Dishwasher Dialogues American Infantilism

Capitalist Art Run Amuck

By: Greg Light and Rafael Mahdavi - Jan 21, 2026

Dishwasher Dialogues American Infantilism

Capitalist Art Run Amuck

Rafael: We read incredible amounts of books, poetry, philosophy, theatre, novels, history––you’d think somebody would appreciate our potential.

Greg: Appreciation! For reading and having ideas? Not likely. Everyone read and had ideas.

Rafael: To make any headway, ours had to be the straightforward approach, knocking on doors. Who are you? What do you want? And finally, we did it ourselves. And I went to galleries with my slides.

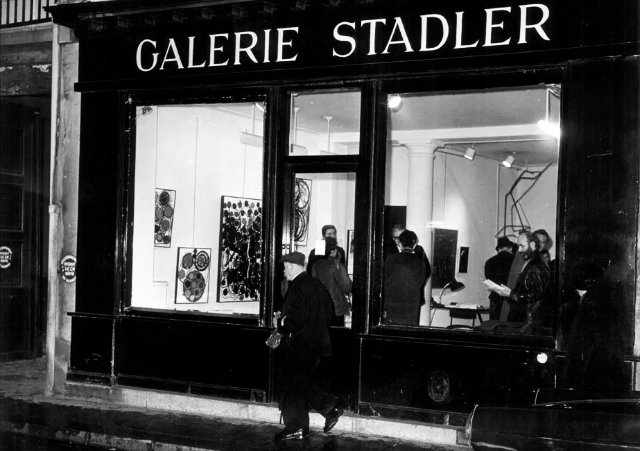

Greg: And you were successful. I remember your first show at Galerie Stadler in Saint Germain de Près.

Rafael: You’re somewhat confused here. My first show––the one with the little cardboard boxes––was at the Centre Culturel du Marais, on the Rue des Francs Bourgeois. I don’t remember the canvases, but I remember the cardboard boxes. My first show at the Galerie Stadler on the Rue de Seine were photo-canvas works, and some had the word Picnic stenciled on the bottom, I think.

Greg: I forgot about the Centre Culturel du Marais. But I do have a faint memory that the title, or the theme, of that first show at the Centre Culturel du Marais was Picnic. It was a solo show, a fair number of large paintings which picked up the idea of a menacing incident in the park, with familiar picnic items like the grass, a picnic basket, but also with unfamiliar items like a gun and suggestions of a murder or violent death. You wanted the invitations for the vernissage, to be unique and to echo the odd items at a picnic. You persuaded the Centre to put some of the invitations in small cardboard boxes. Fifty or so miniature “picnic” boxes were made up. Aside from the invitation, the box had a grass green bottom inside and you put in some small objects which suggested the locale in the park: leaves, small branches, pebbles. We went out one afternoon to collect some of these small objects. I think you may have regretted inviting me along and telling me to find whatever I thought suggested a picnic. After the first dozen boxes or so, I suddenly hit on the idea of adding dried dog turds. Who doesn’t appreciate a well-formed turd? It was Paris after all. Dog poo was pretty much everywhere at that time. Some were flushed away in the daily flooding of the gutters, but many were not. You resisted the idea, but I was persuasive. (I am sure in your heart you knew it was a superb idea?) I collected a few of the very driest ones and we took them back to your studio. They had long lost their smell but to make it more palatable (and hygienic) we spray painted them black, so they were entirely sealed. In the end I think you hesitantly put them in about five boxes. I cannot remember what you said to the gallery if anything. I think you saved those boxes for some of the invitees you could be assured would not be horrified or sue you.

Rafael: How can I forget that turd-o-rama? I found a wholesale place where I bought over a hundred little cardboard boxes. We spray-painted PICNIC on all of them, and as you say, we filled them with all kinds of doodads. We placed them on the floor, in no pattern, about two feet apart, and visually when you walked in, it all looked mysterious. It was an installation piece before it was fashionable. I forget what thoughts were behind all this; I had used the word PICNIC on some of my paintings in New York. But here, I had no idea what I was doing, and the gallery owner was polite enough not to ask any questions. He, erroneously, respected artists too much. Art dealers, especially young ones, think artistes know best. They don’t. Most young artists are loud, confident, and wrong. I know, I’ve been there. I forget if there was an opening. We were probably stoned, so I have forgotten everything.

Greg: No doubt we were stoned. But I am certain there was an event of some kind. I can rouse a memory of it. It is when I learned that in Paris an art show opening is called a vernissage. A varnishing. Not something you quickly forget. And my recollection comes with the quality of ‘varnishing’ any memory still standing at our age displays: blurred, suspect, only vaguely possible, but absolutely true.

Rafael: I held on to one of those cardboard boxes for years. I keep my sewing stuff in it, and whenever I mend something or sew on a button, I think of that installation.

Greg: Neither of us held onto one of those black turds. Except for the one that is exhibited in the Pompidou Centre, they are all gone. (OK that is a completely fabricated memory.) That show happened soon after we met, and the sheer thrill of watching you try something new and allowing me to add a crazy idea and see it materialize (even partially) was galvanizing. Limits and boundaries began to peel away; things became possible.

Rafael: But we didn’t stand still in those days. We were in a hurry and had energy, so much energy, and we used it, most often in a void. Somebody once said history is in a rush.

Greg: Just for the young.

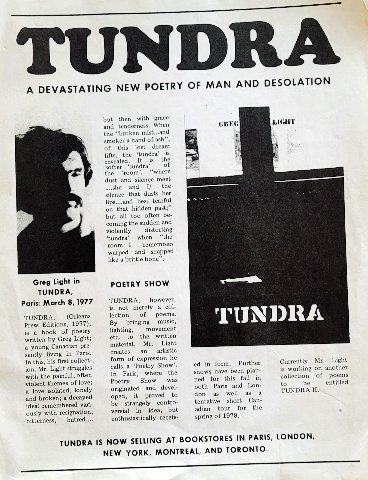

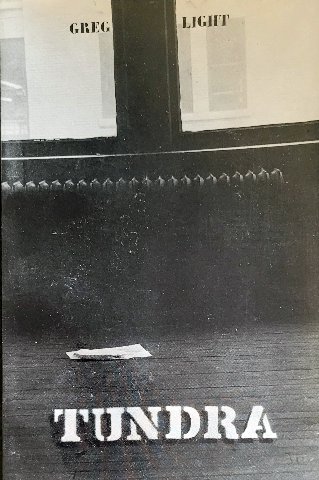

Rafael: We knew no influential people to give us traction. You went to theatres all over town, Greg, with your book of poetry Tundra, which you published yourself, and I did the cover for the book.

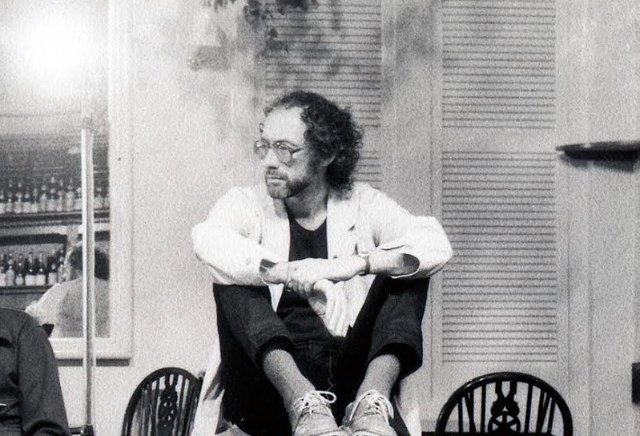

Greg: From the moment I arrived in Paris, I started writing poems. I was disciplined about that. I was under no illusion that I was going to make much selling poems or plays written in English to a French audience. But I was eager to do something with them. The incongruity of coming to Paris to write in English never seriously crossed my mind.

Rafael: But you did say something important at the time. You argued, correctly in my opinion, that living in a non-English speaking country improved your English because you were spared the incessant ephemeral fads and fashions of English usage, generated by TV and radio and songs, foisted on the public. Living in a foreign country helped you taste and relish the words you used and read and wrote.

Greg: Hmm, interesting. I don’t recall the language of TV and radio and ads bothering me too much one way or the other. I am sure I poked at the idea at some point just because that is what we did. But it was never a passion. Exploration was a passion. Experimentation was a passion. So, living in a different language environment led to challenging the idea of working with language in its common forms. I quickly realized I needed to go beyond the language of the text to get to the audience. At some point, I got it into my head that reading poems was not sufficient. They needed to be visualized and performed. I became evangelical about that. Even when I attended poetry readings in London the next year arguing with some established poets about it—Roger McGough comes to mind. And to perform, we needed spaces. Just as you artists needed your studios and galleries. So, you are right, we went to places and spaces all over town. Wherever we could get in, and when we couldn’t, we created out own outlets.

Rafael: Thinking back, we could have used a manager, somebody who knew about finding such places.

Greg: Word of mouth and friends were our manager. The Colours of Power recital was the first thing I publicly performed. There was a hand painted poster featuring a ray of light splitting into a spectrum on the edge of a razor blade. I performed it in a small space on the Quai d’Orsay.

Rafael: The American Church?

Greg: Yes, that’s it. I think they had a little studio space they used for music and small shows. The church also had a gym in the basement where several of us—you, Bentley, Scott, Kenneth, Vince and I and a few others, I can’t remember all the names or faces—played basketball on Sunday afternoons. That is where your delusion of yourself as being a tall guy was shattered. Vince and Bentley put us both to shame. And it showed on the court. I am not sure if the basketball put me onto the studio space or vice versa. I do have a vague memory of working on stage with a black obelisk about Vince’s height. Two meters.

Greg: The first rehearsal space was Bentley’s painting studio. I think it was you who introduced me to Bentley. He was a young American artist, a little younger than me, who had studied with Willem de Kooning in New York. I remember he had some money, meaning he didn’t have to work. For a while you and Bentley and I became a close threesome, to the despair of his French wife—it was she who coined the term ‘American Infantilism’ to describe our approach to life and work and art in Paris. We made a bit of an impact early on; a story, “The Three Musketeers” about the three of us was published in the Paris Metro magazine with the photo taken in your studio, the gun conveniently cropped out. Anyway, Bentley had a large painting studio in which we could rehearse. He also had a theatrical lineage—I think his father had been the lyricist for Damn Yankees on Broadway—and was interested in directing. Who was I to argue? We were all experimenting. And he was an enthusiastic collaborator.

Rafael: Gotta hand it to Bentley, he really got into it.

Greg: The rehearsing was an interesting experience. He had a specific vision of how the poems should be spoken, which my acting ability was not achieving. Eventually, his solution was that I not only memorize the lines of poetry and the staging or blocking of my movements (which was relatively easy), but I also had to memorize a whole host of ‘dots’ which he inserted everywhere in the script between the words: one dot was a short pause; two dots was a medium pause, and three dots was a long pause. He was very dedicated to that technique. We worked on it for days, but I found it impossible. It felt stilted. Nevertheless, it was great performance research for me. It eventually led me to the more stripped-down, natural approach to acting I took to my theatre class and to future productions.

Greg: With Bentley, we started our own press. I collected some of those first poems, plus some new ones under the name Tundra; they were the first thing we published. A first (and only) run of 500—naïve optimism. I still have many left, but at 500 the unit price of the run dropped significantly. Thank God for Leroy. You designed the cover. A dark photo of an empty room. A chambre de bonne?

Rafael: My studio, I think. But I’m not sure. That chambre de bonne was in a fancy building southwest off the Place Victor Hugo, and therefore had a radiator––in the up-market neighborhoods even the maids had the right to central heating. There was a tiny, one-person elevator going up to the fifth floor, and then you had to walk up one more flight. Most things had to be carried up by hand. Lot of floors. Lot of exercise.

Greg: I had forgotten that. I believe the photo was taken when you first moved in before you created your studio. It was empty except for the window, a black radiator beneath the window and a single sheet of paper, one corner slightly folded over, lying on the bare wooden floor. It captured the mood of the book perfectly. We called the press the Orléans Press and its address was Bentley’s place at 16 Rue du Dragon in the 6th. I think the name of the press was my idea, but we kicked it around a bit first. It sounded professional and Porte d’Orléans was just down the street from me and one of the first entry points for the liberation of Paris in 1944. Orléans Press also published two short volumes of your poetry and photos: Thirty Shots 1978 and Double Real Double Sink 1979.

Rafael: Sure, I printed the photos and typed all the pages for each booklet, and each was an edition of thirty. Small, I grant you, but a lot of typing, nevertheless. The energy we had! I also remember we talked about writers and poets who had started presses. Ferlinghetti, Anais Nin, Cesar Vallejo. I never told you, but in 1969 I mailed a postcard to Anais Nin’s publisher. And she sent me a letter in reply. We started a correspondence of about ten letters.

Greg: You did tell me about your correspondence with Anais Nin. There was not much we didn’t talk about back then.

Rafael: I lost her letters when I left New York. I never tried to contact her again. I was turned off by her insinuations about sleeping with her father, a well-known Cuban pianist. Deidre Bair, by the way, also wrote Anais Nin’s biography.

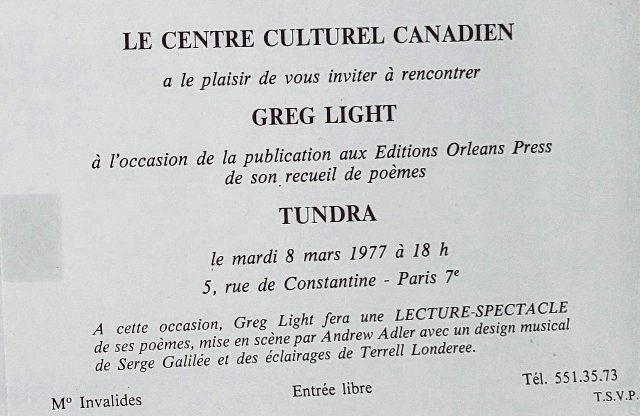

Greg: Our press and Tundra helped me to secure my next performance; at the Centre Culturel Canadien. You designed, Bentley directed, and Vince worked the lights. By then, I was not memorizing dots quite so intensely. It was a wonderful venue with a small theatre and gallery space and sizable membership list. Back then it was located at 5 Rue de Constantine in the seventh arrondissement. Very up market district, near Les Invalides. Amazing luck that they even listened to us. I had virtually no history, but based on a book of poems, a performance philosophy, youth and exuberance, (and being Canadian), they gave me a date. And they billed it as a performance and book launch. So, I sold quite a few copies to boot.

The oddest venue we snagged—I no longer have a clue as to how it came about; maybe they approached us—was a performance of Tundra at the Centre des Arts in Saint Germain-en-Laye, a Parisian suburb some distance to the west of the city. I remember telling the artistic director that although we employed music, movement, and lighting. it was all in English and it was poetry. They said, no problem, the audience would be high-school students studying English and they would be able to follow it. When we got there, it was a large auditorium. For this show we had added live music. Scott was playing guitar and Kenneth was playing piano. Each were following the music score by the light of a solitary candle.

Rafael: I recall that Scott admired Henry Kissinger, ergo he was probably weird and right wing.

Greg: He could be a bit prickly. Whereas Kenneth always struck me as laid back. They flanked me on either side of the stage. The audience arrived and packed out the hall – a dozen teachers and 250 plus school kids, all nine or ten years old. We began. I completely lost their attention in the first 2 or 3 minutes. I tried stuff to engage them; like suddenly shouting out lines in strange voices. This halted the commotion for about a second, followed by waves of “ooohs and aaahs” in that young person mocking tone, magnified by hundreds of voices. Absurdly, we continued, as did they, a sea of kids talking and acting out to a determined trio performing poetry in a resounding vacuum. Scott told me later that near the end of the performance—when a teacher finally managed to battle his way up to the stage to shout that they couldn’t hear a thing—he suddenly realized he had spent an hour playing his guitar for himself and a candle. He was not happy.

Rafael: Weird. I wasn’t there that day. It must have been nightmarish, one of those dreams from which you wake up and happily realize it wasn’t real. But in your case, it was real, a nightmare inside out.

Greg: I think you were working the bar at Chez Haynes that day. Dealing with your own nightmarish kinds of audience. The moment was unsettling, to be sure, but the incongruity of the incident made it feel curious and strange more than maddening. The kids were the show. I should have video-taped it. I still have no idea why or how we came to be invited there. Saint Germain-en-Laye was a communist-run municipality at the time. We had asked the artistic director when we first visited the venue to discuss the details of the performance, if politics had any influence on what he chose to stage. He insisted the communist authorities never interfered with his artistic decisions. He had complete independence and autonomy. Although, he then admitted that he was a communist himself, so they didn’t have to worry about his decisions or choices.

Greg: How that mélange of politics and art led to us performing Tundra for school kids is still a mystery. We were clearly unorthodox (revolutionary?) on many levels and maybe that was enough. And, as far as I know, we didn’t pose an anti-communist threat. Then, again, perhaps it was all a set-up. We might have been invited and exposed to the students as a cautionary tale of what capitalist art run amuck can lead to.