Jimmie Durham: At the Center of the World

Controversial Traveling Retrospective

By: Charles Giuliano - Jan 27, 2018

The 1993 Whitney Biennial focused on identity politics. That included intriguing and enigmatic sculptures fabricated from found materials by Jimmie Durham. By then he was living abroad in a variety of locations having departed in 1987.

I was intrigued by a series of weapon-like wall sculptures fabricated from vintage gun parts, carved branches, and coyote bone. The opportunity to see more of this innovative and provocative work would take decades.

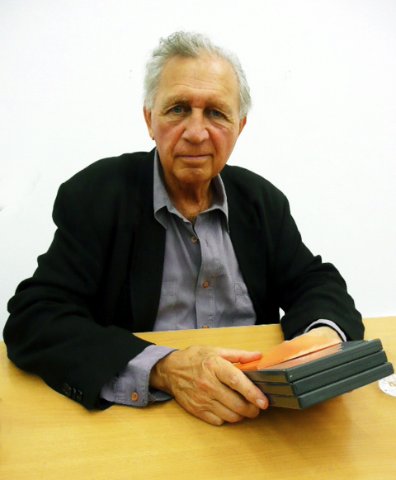

For reasons of declining health the 77-year-old artist did not return to the States for the opening of a long overdue retrospective Jimmie Durham: At the Center of the World organized by the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, curated by Anne Ellegood, senior curator, with MacKenzie Stevens, curatorial assistant. It traveled to the Walker Arts Center and ends its run at the Whitney Museum on January 28.

Since that high profile exposure in 1993 the artist in self imposed exile has largely remained under the radar in his native land. Global curators have shown Durham’s work in major exhibitions including the Venice Biennale and Documenta. He has been seen in European museums and has major gallery representation abroad.

Reflecting the title of the exhibition wherever the artist settles, temporarily, or for extended stays he lays down a claim. A long stick with mirror attached is thrust into the ground. This reflects the practice of conquistadors staking out the New World in the name of sovereign and nation.

There is a medieval overtone to this. Maps of a flat world had Jerusalem, the city of Christ, as their epicenter. With irony the artist, who suffered identity backlash from the indigenous people of America, states that he is a world citizen. Indeed, wherever he chooses to be is the center of the world. This is of course dubious but, arguably, it is the center of his personal world.

We may regard this as a creative exorcism of hurtful separation from family, friends and heritage. This “claiming” is both clever and poignant which is a quality that resonates through this exhibition. The work is generally simple in means, intuitive and witty, while deeply profound.

Supporters of the current exhibition, including major curators and critics, regard him as one of the most original, vital and influential American artists of his generation.

Arguably, there are an equal and vociferous number of detractors. The attacks are not about the work, which is universally acknowledged for its significance, but about the politics of identity. While stating Cherokee heritage, his detractors insist that it is a false claim as he is not enrolled in any of the three major branches of the Cherokee Nation.

Before moving to New York and focusing on making art he had been an activist.

He fought for land rights and health care and against tribal enrollment with the American Indian Movement, and then as director (from 1974 to 1979) of the International Indian Treaty Council, which was recognized by the United Nations as an NGO in 1977.

The 1990 Indian Arts and Crafts Act (IACA) made it illegal for anyone falsely claiming Native ancestry or tribal affiliation to sell art as such.

First-time violators of the law are subject to a $250,000 fine, five years in jail, or both.

After a 1993 profile appeared in Art in America which quoted him talking about being Cherokee and a “Cherokee artist,” Durham wrote a letter to the editor stating: “I am not Cherokee. I am not an American Indian. This is in concurrence with recent US legislation, because I am not enrolled on any reservation or in any American Indian community.”

He has commented on the controversy on different occasions but shut off discussion in a recent interview because he did not want to arouse more backlash.

“I am a Cherokee artist who strives to make Cherokee art that is considered just as universal and without limits as the art of any white man is considered.” He has stated “…If I am able to see both Cherokee art and all other art as equal. It is important to me (that) I am Cherokee. BUT I AM NOT A CHEROKEE ARTIST. That difference means to me that I try to join up with artists throughout history who are artists, with no special claims beyond art, but also to claim art as the reason to make art.”

There are complex elements that underscore issues that attach to Durham. Native American Art has gotten a token of recognition it deserves by museums, curators, collectors and critics. Despite an era, and informed generation of globalization, gender and identity Native American culture continues to be the least recognized category for critical study.

A part of that reflects division, tribalism and territorialism within the culture itself.

It is the vociferous rhetoric of attacks that prompted the artist to state in 2011 “I’m accused, constantly, of making art about my own identity. I never have. I make art about the settler’s identity when I make political art. It’s not about my identity, it’s about the Americans’ identity.”

There is the thorny point that a retrospective is being organized by major American museums of work by an alleged, or not, Native American artist. That occurrence is as rare as hen’s teeth. I have personally known and worked with a number of “enrolled” artists who richly deserve being honored for lifetime accomplishments. There is an even greater number of mid career and emerging artists who remain ignored by the mainstream art establishment. That neglect is criminal in its monstrosity.

In bringing these issues, pro and con, front and center Durham deserves all the more praise and recognition as one the foremost artists of his generation. He has stirred the pot of egregious curatorial complacency.

Here in the Berkshires, for example, only the Berkshire Museum, under former director Stuart Chase, has shown contemporary Native American Art. In its survey of Canadian art First Nation artists were shown at MASS MoCA. Other than that I know of no Native American artist it has featured.

Can we set aside the rhetoric and share a visit to the exhibition?

It was a rich, diverse and truly delicious visual experience.

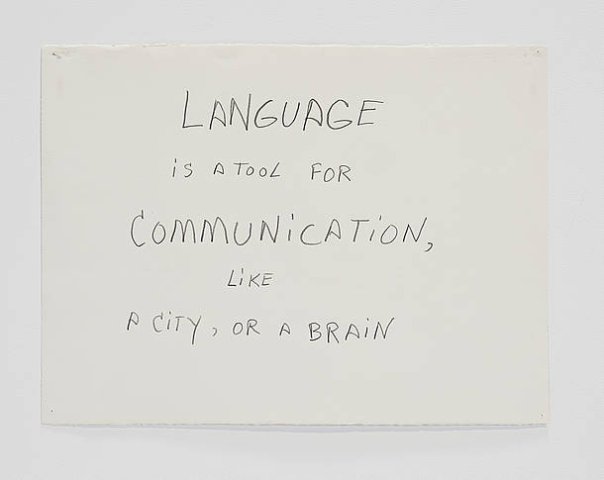

While “native” in the selection of natural, bird and animal elements, including taxidermy and skulls, there is a deflectingly outrageous humor. This is often conveyed in the block letter, primitivism annotations of the artist.

This is inherent and consistent to the cultural paradigms of Native American humor. There is the tradition of the coyote prankster. A detractor noted that the rabbit prankster is traditional in the South West.

For a map through obstacles of the cultural minefield one might start with the wit and wisdom of Vine Deloria, Jr. His iconic “Custer Died for Your Sins” is a good beginning to start with when confronting the serious fun of Durham.

It is impossible not to laugh your way through the exhibition.

Start with Pocahontas Underware in which her alleged red skimpies are adorned with feathers. It’s a history lesson rerouted through Victoria’s Secrets.

In development of his work the artist has drawn upon many sources and traditions. The look, particularly in the early pieces, reflects decorative approaches. When, through trade, objects such as rifles and tools were acquired they were deconstructed and reclaimed through crafts applications.

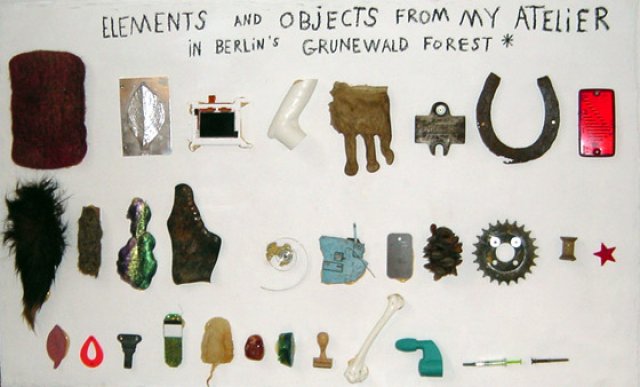

For materials wherever Durham resides he is a scavenger of detritus. The studio/residence, a converted convent near Naples, is a clutter of stuff. A recent interview described Durham trying to clean out and discard from his work and storage spaces. Significantly, this produced four new pieces. It is reported that he creates some 40 or so works annually. During time in Venice, for example, shards of Murano blown glass became elements of the work.

This can result in hilarious objects. When in New York, for example, a car muffler retrieved from the trash, an utterly useless piece of junk, was laboriously and lovingly decorated.

In the tradition of Dada master, Marcel Duchamp, this evolved as a found object then further crafted as an assisted readymade. It is displayed suspended from the wall hanging on a string. That reminded me of the funky, slapped together stretchers and strings of Jean Michel Basquiat.

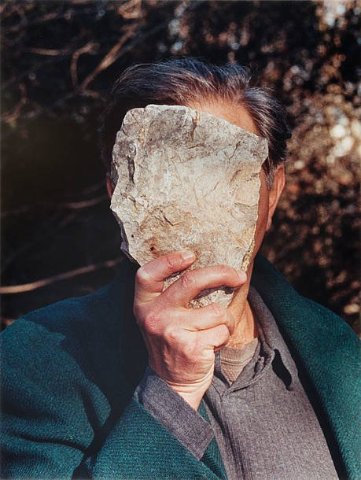

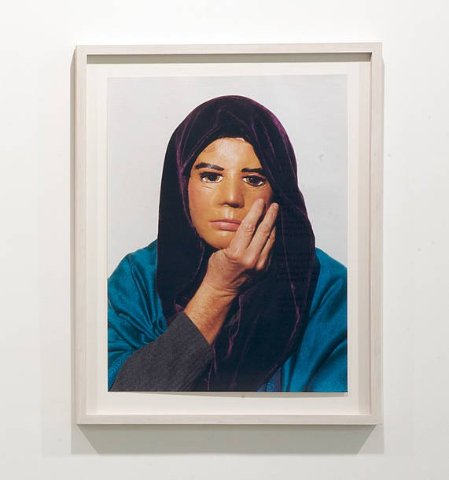

Many of Duchamp’s concepts are embedded in the practice of Durham. There is a commonality of visual puns, mad fun, conceptualism and drag. Like Duchamp’s Rrose Selavy there are photographs of Durham’s feminine alter ego and tricks before the camera. He creates a stone face by literally holding a large, flint-like, flat rock obscuring his features. Other self portraits entail masks and costumes. He assumes multiple personas and creative personalities.

There is a cast of characters we encounter. This includes a life-size image of the conquistador Hernán Cortés, the 16th-century invader of Mexico. It is fabricated from pipes and pullies. It is accompanied by a figure of Malinche, Cortés’s slave, interpreter and mistress. History regards her as a traitor and copout but Durham invests her with poetic ennui. There is sadness conveyed by a skeletal armature over which a bra is draped signifying breasts. As so often occurs in this retrospective, with wit and an economy of means, the artist prods us to revisit history and the devastation of colonialism.

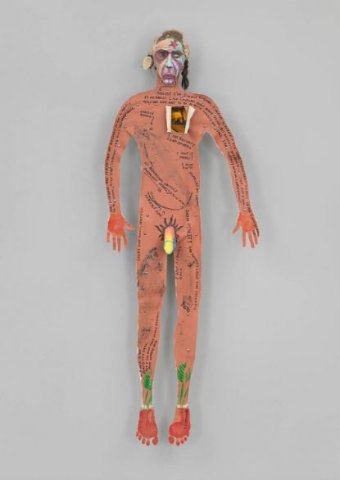

Although the work of Durham is not well known the most familiar and iconic piece is a 1986 “Self Portrait.” It was requested/commissioned by the Kenkeleba Gallery in the East Village and included in a group show. The scathing image reveals his caustic state of mind on the cusp of leaving roiling conflict in America.

Onto a piece of canvas the artist lay down and his companion, Maria Thereza Alves, traced his outline. The excess was removed and resulted in a painted skin enhanced with a painted mask as well as a carved, enormous penis. There is text written over the object. The artist as “skin” or should we say “red skin” evokes the tormented self portrait of Michelangelo as flayed held by the martyred St. Bartholomew in The Last Judgment fresco in the Sistine Chapel.

The graffiti like text on the image states in part “Indian Penises are unusually large and colorful…My skin is not really this dark, but I am sure that many Indians have coppery skin.”

In New York it is amazing what can be recycled from trash. It was a resource for the Combines of Robert Rauschenberg. Ironically, the artist also shared Cherokee heritage but never asserted an identity as a Native American Artist. This was also true for the avant-garde, non objective painter Leon Polk Smith.

It is mind boggling to encounter Durham’s altered moose head. It is missing an antler. Accordingly it was trashed and reconfigured by the artist. The imposing skull is mounted on a scrappy pedestal. Ignoring simulacrum the missing element is not reconstructed in a trompe l’oeil manner. Instead, it evoked gales of laughter to see its pipe configuration.

Many are flummoxed, including artists, at the enormous material value attached to the found objects, readymades, combines and assemblages of artists. Durham reflects on this with a short film, 2003, “Pursuit of Happiness.”

It is a capsule of his improbable success in the art world. A young man Joe Hill (Anri Sala) lives in a dilapidated trailer in the desert. We see him on scavenger hunts collecting stuff tossed out windows by passing cars. This includes road kill. From this worthless trash he make collages. A major gallerist offers a show attended by the art world’s glitterati. Later, the dealer hands wads of cash to the artist. Subsequently, Hill torches the trailer and splits for Europe. The final scene shows him hanging out with the literati in a Parisian sidewalk café. It’s an amusing take on the artist’s actual experience.

Other performance videos focus on obsessive/compulsive actions. In one we see large rocks hurled at an old refrigerator. The dented object is displayed in the room with the video. In another piece “Smashing” the artist is seated at a generic metal desk. A series of individuals present him with objects. With a large rock Durham demolishes them as pieces fling off. At the end of each incident, from the desk, he produces a certificate which is stamped, signed, and presented. It is assumed that the resultant document, properly framed, becomes an object of value. In a similar manner Duchamp created and sold lottery tickets which are collector’s items.

While a long time coming this was a richly diverse, complex and thought provoking overview of one of the foremost American artists of his generation. An uncanny testament to its power and impact is its ability to kick up a mushroom cloud of dust.