Costa Rica

Part One: Central Valley and Sarapiqui

By: Zeren Earls - Jan 31, 2010

Why go? Costa Rica, in its small space the size of West Virginia, has major attractions: beaches, volcanoes and national parks teeming with birds and wildlife. It is a nature lover's paradise. Besides its tropical bounty, it has the best working democracy in Latin America; a peaceful country with no national army, it boasts the highest literacy rate in the region after Cuba. It had been on my short list for some time. With the incentive of no supplement for single room accommodations from Overseas Adventure Travel, I signed up for the "Most Affordable Costa Rica" itinerary.

Normally I do not travel during holidays; upon arriving at Boston's Logan airport, I quickly realized that this would be my first and last such mistake. At 5 am on December 31, all of Latin America seemed to be returning home from visiting relatives. Loaded with Christmas gifts, passengers formed long lines to travel to Miami for their connecting flights to Caracas, San Juan, San Jose etc. Fortunately, we were able to depart on schedule, thus avoiding a predicted snow storm later in the day. Bundled up for Boston's 20-degree weather, I became three layers lighter when we reached Miami at 76 degrees.

San Jose is on Central Time; adjusting my watch by one hour, I settled down for the next four-hour leg of my total flight of seven. San Jose airport was crowded, apparently a daily state because of large number of visitors. It took an hour to clear passport control and customs. Although only 8 degrees north of the equator, San Jose was cooler than Miami because of its elevation at 3000 feet. Temperature in Costa Rica is determined by altitude rather than season.

A van arranged by the local OAT office delivered me to the centrally located Clarion hotel, twenty-five minutes from the airport. Despite my lack of sleep since 4 am, I could not help but notice all the littered streets as we sped by. Claiming my key from Pablo Yee, our trip leader, I carried the welcome cocktail to my room, too tired to enjoy it in the lobby. I dropped off to sleep instantly; the sound of fireworks at midnight reminded me that it was New Year's Eve.

Donning sun screen and mosquito repellent, which are needed daily in the tropics, I descended to the breakfast room. Among the buffet offerings were a platter of fresh papaya, pineapple and watermelon, scrambled eggs and gallo pinto, the-rice-and-bean dish that Costa Ricans eat at all meals. The sunny terrace beckoned, although too cool without a jacket. After breakfast, our full group of fourteen met with Pablo for a briefing. There were changes to the day's itinerary because of January 1 being a national holiday. Although the San Jose city tour was deferred to the end of our trip, I will include it here to stay true to the original itinerary.

Founded in 1737, San Jose, the country's largest city, is also its capital. It is situated in the Central Valley, where three of Costa Rica's population of four and a half million live. High enough for an ideal year-round climate, it is surrounded by a cluster of towns whose residents commute to work in the city daily, contributing to its bustling life and rush-hour traffic. It has lush green parks, residential homes decorated with iron grill windows and garden walls topped with barbed wire. Government offices and banks give it a modern skyline. Its walkable central part has most of the museums and theaters.

The National Theater is an architectural treasure. Finished in 1897 with tax money from coffee exports, it is patterned after European opera houses. Its façade, overlooking Central Park, is Renaissance style, with figures representing Music, Fame and Dance. Statues of Beethoven and Calderon de la Barca fill niches on either side of the entrance. The lobby inside has marble floors and columns. The grand staircase and foyer on the second floor feature Italian marble sculptures. The building's only native material is its parquet floor made of Costa Rican wood.

Across from the congress building is the National Museum, which features an excellent exhibit of pre-Columbian artifacts, some dating from 12,000 years ago. All of Costa Rica's history and historical art are represented here, in buildings surrounding a garden displaying imposing stone spheres several feet in diameter. Unique in the world in terms of size and spherical perfection, they are believed to have been made, starting in 300 AD, as territorial markers symbolizing high rank. The museum also has noteworthy displays of jade and gold ornamental objects.

From San Jose, we headed north on the Pan American highway in a minibus, riding through Central valley to Alajuela, where we stopped for lunch, viewing butterflies nearby. Casado is the typical lunch plate with rice and beans, which come with a choice of fish, chicken or beef, accompanied by fried plantains and steamed vegetables. Soup and salad accompany most meals. Health is a top priority in Costa Rica, where 97% of towns have potable water. We enjoyed raw salads throughout our trip.

The day's treat was a visit to the Doka Estate, a coffee plantation run by a third-generation family. Originally brought from Africa, coffee plants are started out as seedlings. Then they are planted near shade-bearing trees to keep them from scorching. Ripened red berries are handpicked, mostly by Nicaraguan laborers, in baskets with a 25-pound capacity. After the outer skin is peeled, the berries are floated in water and those that rise to the surface are discarded. Fermented and sun-dried beans are roasted at temperatures of 15, 17 and 20 degrees Celsius, each temperature determining the mildness, from house blend to French Roast to Espresso, the strongest. The biggest export market is Europe; sold as beans to Germany, coffee is bought back decaffeinated. Costa Rica provides 70% of Starbuck's supply. Locals call this valuable crop the grano d'oro, or golden seed. Early oxcarts that transported coffee are now colorful keepsakes; gigantic bronze coffee bean sculptures adorn cities.

Passing the continental divide that separates Costa Rica's rainy Caribbean from the dry Pacific side, we entered the Brauilo Carrillo National Park. Coffee plantations gave way to steep slopes and forests in the clouds; downpours alternated with moments of tranquility to appreciate waterfalls and the mineral-filled yellow Rio Sucio. Our superb driver, Oscar, negotiated narrow roads with heavy truck traffic through torrents, finally turning off highway 32 to Sarapiqui and the Trimbina Biological Reserve near Virgen, our destination for the next two nights.

The Sarapiqui Rainforest Lodge is a group of indigenous-style huts with thatched roofs in a region known for 850 species of birds. At dawn, we watched birds feast on bananas put out by our tour leader, Pablo. Later, donning life vests and helmets, we enjoyed rafting on the Sarapiqui River. In groups of five, we front- and back-paddled and stopped, following our captain's commands as we moved through almost still waters and rapids with churning white peaks over rocks. During a shore break from our two-hour expedition, we learned about tiny poisonous frogs, and tasted fresh coconut straight from the tree. A first time experience for me, river rafting was a highlight.

Pineapples head the list of Costa Rica's agricultural exports, which also include mangoes, bananas and flowers. Belonging to the Bromeliad family, which requires daily water, shady soil with drainage and stable temperatures, pineapples are best suited to the equatorial region. In a tented car pulled by tractor, we visited the country's first organic pineapple farm, started in 1991. Plants grow through black plastic sheets laid down for weed control. The fertilizer used contains no chemicals. Pineapple has to be stressed to come up; ethylene gas is used to have them shoot up all at once. One plant gives ten shoots, one of which is replanted. Ten thousand shoots are planted a day; workers are paid by the number of shoots they plant or pick, earning $35 a day.

After picking, pineapples are washed in water, with soft or brown ones discarded. Then they are placed in boxes, weighed not to exceed twelve kilos (twenty-five pounds), as the company is paid by the box. Labeled boxes are taken into freezer rooms at 45 degrees for four days to ferment before shipping. Unfortunately, the company is phasing out all but 30% of its organic production, as the demand from the US has decreased with the economic downturn. The major US buyer of the organic supply is Whole Foods. The Golden variety, developed in Costa Rica, is unique to the country; Brazil, where pineapple originated, is the world's largest exporter. At the end of the tour, we sipped pina coladas from fresh pineapples. Advice on how to select a pineapple at the market overturned existing myths. We are to pick green fruit with firm bottom leaves when pulled. Leaves that pull out easily indicate fermentation due to excessive handling!

The evening's superb lecture was by a specialist on bats. Fifty percent of the world's bat population lives in Costa Rica, which has three hundred species, including ones that eat fruit, insects, and nectar, as well as viper bats. These flying mammals are beneficial as each bat eats one thousand mosquitoes per night; they are also pollinators; help forestation by dispersing seeds, and produce a natural anticoagulant. Seeing a variety of bats in expert hands was most enjoyable.

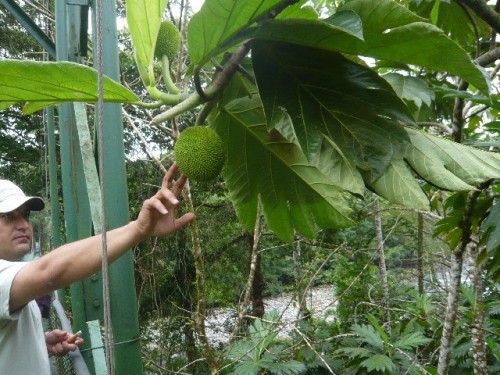

Walking through Triamba National Park was a bounty of discovery. We crossed two suspension bridges: one over the Sarapiqui River, the other over the forest canopy. Rain forest trees have no age rings; trees stunted for a long time due to lack of sunshine shoot way up as soon as they find an opening left by an existing tree toppling over. We gazed at walking-root palm trees, monkey ladder vines; pink and red ginger plants and, heliconias, while leaf cutter ants trailed the forest floor.

Our discovery of the Sarapiqui region ended with a visit to the Anthropology Museum. The Botos, an indigenous group, inhabited this part of Costa Rica prior to Spanish colonization. The museum has artifacts of their daily lives, including gourds decorated by scraping, pecking and cutting; bags called chacaras, woven with purple fibers; and mastates or painted bark cloth fashion items from various species of tree, each giving a different color and texture. Dyes and paints from leaves and roots produce intense yellow, muted brown, deep black, or green, which are used to create geometric patterns and stylized animal designs. The Botos were animists, and used herbal medicine and magical stones for healing. Near the museum are their burial grounds.

Our appetites whetted in this exotic region, we departed for La Fortuna in pursuit of further discoveries.