Programming Joy

Cultural Strategy in an Age of Exhaustion

By: Chad Bauman - Feb 12, 2026

There is a familiar critique that surfaces whenever regional theaters announce seasons rich with work that foreground delight: that they are programming for joy as a way of “playing it safe.” Beneath this critique lives an assumption that comfort is synonymous with complacency, that pleasure signals avoidance, and that the only honest aesthetic response to crisis is confrontation.

It is a compelling narrative, especially in moments that feel politically, socially, and environmentally precarious. If the world is on fire, shouldn’t the stage mirror the flames?

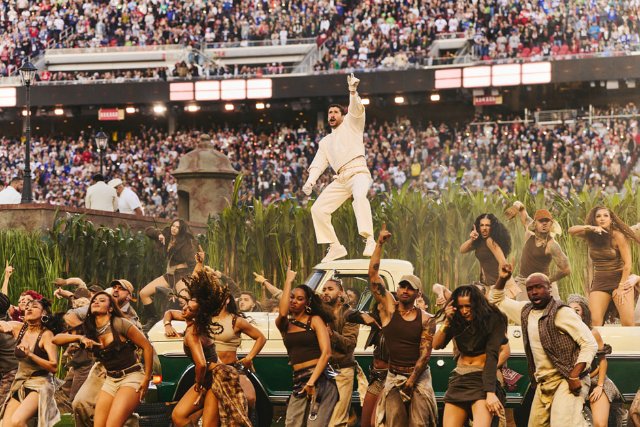

And yet, I keep returning to Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl performance.

Few global artists have been as scrutinized and politicized as he has. His communities remain persistently endangered, and his homeland exists within the long, uneasy tensions of American territorial power. By every expectation of protest performance, that stage could have been a site of fury, a reckoning, an indictment, a civic interrogation broadcast to the largest audience on earth.

Instead, its force lived in beauty, joy, and love.

That choice was not an evasion of politics but an intervention within it. The performance resisted by offering what feels most endangered in public life: celebration without apology, cultural pride without translation, tenderness without qualification. It offered radiance where many expected rage, a beacon rather than a battle cry.

I think about this often when regional theaters are critiqued for programming work that foregrounds joy. Too frequently, such programming is dismissed as “safe,” as though comfort were incompatible with courage.

But that critique rests on a narrow theory of change.

It assumes resistance must mirror its opposition. It assumes the only legitimate artistic posture is one of visible struggle, that art must wound in order to be honest, must indict in order to be relevant, must exhaust in order to be meaningful.

Bad Bunny’s performance suggests another paradigm.

If one believes change only comes from fighting fire with fire, joy can look like retreat. Celebration can appear frivolous. Beauty can feel insufficient to the scale of injustice. But if one accepts the proposition that love is stronger than hate, then joy becomes insurgent. Celebration becomes refusal. Comfort becomes care enacted at scale.

In that frame, programming for relevant and meaningful joy is not institutional retreat but cultural strategy.

To create spaces where audiences experience delight, belonging, laughter, and emotional replenishment, particularly in eras defined by exhaustion and fear, is to push directly against the conditions despair relies on. Authoritarianism, bigotry, and violence do not merely operate through policy and force; they operate through depletion. They thrive when communities are isolated, when imagination is narrowed, when the future feels foreclosed.

Joy disrupts that machinery.

A theater filled with laughter is not disengaged from the world’s crises; it is metabolizing them differently. It is offering audiences oxygen. It is reminding them of their shared humanity. It is cultivating the emotional resilience required to continue the work of justice beyond the auditorium walls.

This revelation is not new. Historically, joy has often functioned as a means of survival. Social dances, carnivals, drag balls, and festivals have long held political power precisely because they insisted on pleasure in the face of oppression. They declared, again and again: We are still here. We are still worthy of celebration.

To witness joy under conditions designed to extinguish it is to witness defiance.

Regional theaters, situated within their own civic ecosystems, have the capacity to extend that lineage. When they program stories that center love, humor, kinship, or communal triumph, they are not necessarily turning away from struggle. They may be tending to the emotional infrastructures that make struggle sustainable.

This does not mean all programming should be joyful, nor that confrontation has no place on our stages. Anger has artistic value. Protest has aesthetic necessity. There are truths that only rupture can reveal. But the binary that positions “serious” work as courageous and “joyful” work as safe flattens the political vocabulary of art. It reduces the spectrum of resistance to a single emotional register.

In reality, cultural change has always required multiple strategies operating simultaneously: protest and restoration, critique and imagination, grief and celebration.

Joy is the register that imagines what life could be absent harm. It offers audiences not just analysis of the present, but sensory evidence of a more humane future. It lets people experience a retreat from what is and hold what we can aspire to. That matters because people fight harder for futures they can picture.

In this way, programming for joy becomes future-building work. It seeds the belief that life can be fuller, kinder, more connected than current conditions allow. It replenishes the very capacities, empathy, hope, relationality, that movements for justice depend on.

Joy is not anesthetic. It is fuel.

Bad Bunny revealed this on one of the most surveilled stages in the world. He did not dilute his politics by choosing beauty; he expanded their reach. He offered tens of millions of viewers worldwide an encounter with cultural pride that did not ask permission, did not translate itself for comfort, did not cloak itself in anger to be legible as resistance.

He made love visible at scale.

Regional theaters, in their own way, can do the same. Not through spectacle measured in broadcast numbers, but through intimacy measured in human proximity, shared breath, shared laughter, shared emotional release.

In times when audiences arrive carrying burnout, grief, and dread, offering them replenishment is not avoidance. It is care. It is civic work. It is an assertion that communities deserve not only critique of the world as it is, but experiences of the world as it could be.

Joy is not the absence of resistance. It is resistance that imagines a future worth fighting for, and invites us, if only for a few hours in the dark, to live inside that future together.

Chad Bauman is artistic director of Milwaukee Rep which has recently expanded.