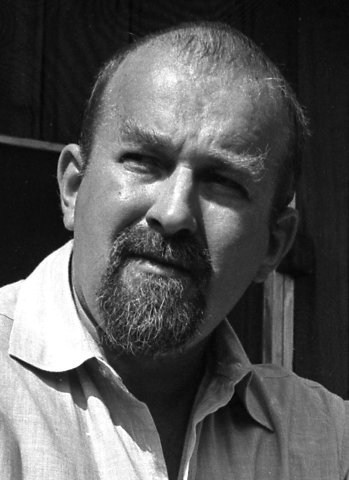

ICA Director Sue Thurman

Thriving on Newbury Street

By: Charles Giuliano - Feb 13, 2026

From its inception in 1936, the Institute of Contemporary Art has endured a daunting existential struggle. As late as 1971 the Museum of Fine Arts appointed a part time curator of contemporary art. Lack of interest for modern and contemporary art resulted in a community which did not significantly support institutions, collectors, galleries and artists. The story of the ICA represents the struggle to overcome that indifference. Relocated to Newbury Street, it thrived from 1963-1968 under director Sue Thurman.

ICA Directors

- Nathaniel Saltonstall, (1903-1968) architect, founded Boston Museum of Modern Art, 1936- 1939 became Institute of Modern Art in 1939

- James Sachs Plaut, (1913-1996) director 1939-1942, 1946 to 1962 in 1948 renamed Institute of Contemporary Art

- Thomas Metcalf (trustee and acting co-director) 1942-1946

- G. Russell Allen (trustee and acting co-director) 1942-1946

- Thomas Messer, (1920-2013) director 1956-1962 (Soldier’s Field Road 1960-62) Then Director Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, 1962-1988

- Sue Thurman, (1927-2012) director 1963-1968, New England Life Hall, Newbury Street

- Andrew Cornwall Hyde, 1968-1971, 1973-1974, Died, January, 2008

- Christopher Cook, 1971-1972, a conceptual term on leave from Addison Gallery, Andover

- Sydney Roberts Rockefeller, Born 1943, acting director, 1973-1974

- Gabrielle Jepson, 1975-1978

- Stephen Prokopoff (died 2001 at 71) 1978-1982

- David Ross, 1982-1990, left to head Whitney Museum and other posts

- Milena Kalinovska, 1990-1998 later, curator of the Gwangju Biennial, from 2004 to 2015, at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden as the Director of Public Programs and Education, and from 2015 to 2018 at the National Gallery Prague as the Director of Modern and Contemporary Collection

14. Jill Medvedow, 1998 to 2024

15. Nora Burnett Abrams, 2024 to present

Locations

1936, 114 State Street, Fogg and Busch Reisinger Museums

1937, 14 Newbury Street

1938, Boston Art Club, 270 Dartmouth Street

1943, 138 Newbury Street

1956, 230 The Fenway, second floor of the School of the Museum of Fine Arts

1960, 1176 Soldier’s Field Road, designed by Nathaniel Saltonstall

1963, 100 Newbury Street, New England Life Hall

1968, 1176 Soldier’s Field Road

1970, Parkman House, 33 Beacon Street

1972, 137 Newbury Street

1973, 955 Boylston Street, former Police Station, interior by Graham Gund, 6,000 sq. ft.

2006, Move to waterfront in building designed by Diller, Scofidio & Renfro, 65,000 sq. ft.

2018, ICA Watershed, East Boston 15,000 square foot annex.

.

Founded by the architect Nathaniel Saltonstall as Boston Museum of Modern Art, a satellite and partner of MoMA in 1936 as a kunsthalle (non collecting museum) there was an initial focus on modernism. A show of Picasso organized by MoMA included his “Guernica” when it traveled to Boston.

That relationship ended in 1948 when, under director James Plaut, it was renamed Institute of Contemporary Art. Largely deflecting the post war emergence of the New York School Plout’s programming went to the edge of but never crossed the line of abstract expressionism. The ICA honed to forms of expressionist figuration. That branded the ICA as a traitor to progressive art and bastion of a conservative take on modernism.

This opened up a bit under Thomas Messer, who by his own admission was conservative. A Czech born curator, his orientation was to Europe including the first American museum exhibition of the Austrian expressionist, Egon Schiele. While he organized important exhibitions the ICA continued to be marginalized.

When Messer left to become director of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation in New York he recommended Sue Thurman, then director of the Delgado Museum of Art in New Orleans.

An immediate mandate was fundraising. There was a patron’s dinner and auction the prize lot being a donated work by Hans Hoffman. Because of a strong attendance there was limited seating in the Saltonstall designed structure on Soldier’s Field Road. The spillover was seated in tents to which bids were announced. The event was a success and Thurman proved to be an effective fundraiser.

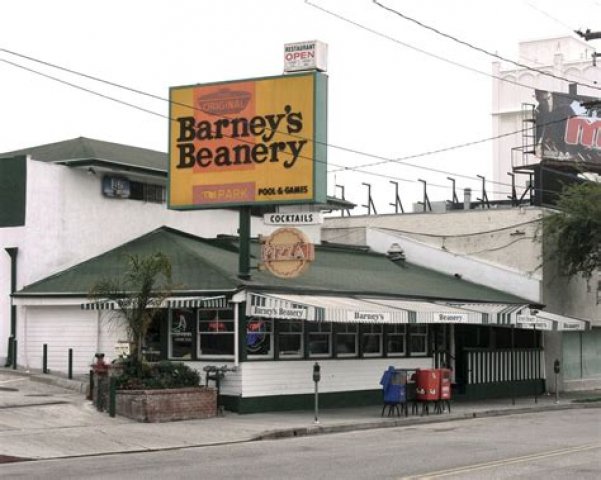

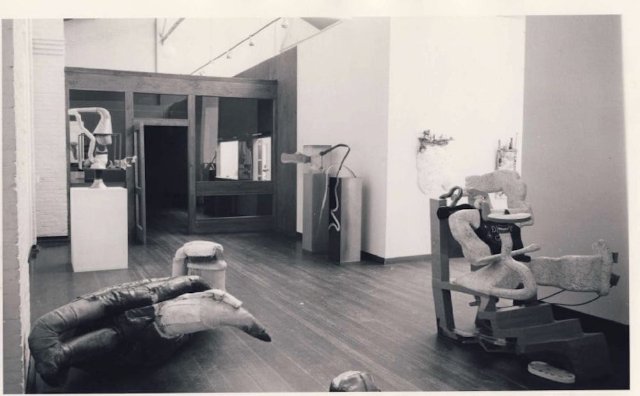

With Saltonstall they explored space to move the ICA. Largely through his contacts they arranged a lease on favorable terms in New England Life Hall on Newbury Street. The wide, horizontal space has large windows facing the street. Thurman leveraged that walk by access to make the exhibitions enticing for visitors. For the five years of her tenure the ICA was the heart and soul of Boston’s lively gallery row. That provided a spark which marked a turning point for contemporary art in Boston.

In addition to astute administrative and fundraising skills, for the first time, the ICA was truly immersed in cutting edge issues of contemporary art. There were related performances and lectures in New England Life Hall. Here are highlights of her program.

1964

The 32nd Venice Biennale signaled the arrival of American Pop art on the international scene. A concurrent exhibition at the ICA celebrated the artists representing the U.S. in Venice: John Chamberlain, Jim Dine, Jasper Johns, Morris Louis, Kenneth Noland, Claes Oldenburg, Robert Rauschenberg, and Frank Stella.

1965

London: The New Scene, organized by the Walker Art Center, was one of the earliest exhibitions to introduce U.S. audiences to the work of Bridget Riley.

1965

At an early moment in the history of electronic media and video art, Art Turned On brought together some of its leading pioneers, including Dan Flavin, Robert Whitman, and Fluxus artists Ay-O and Joe Jones. Marcel Duchamp attended the exhibition and took a special interest in Jones’s Music Plant.

Received ideas about mark-making, gesture, and authorship came under scrutiny in Painting Without a Brush, presenting works by Helen Frankenthaler, Morris Louis, Jackson Pollock, Jean Tinguely, and Andy Warhol, among others.

1966

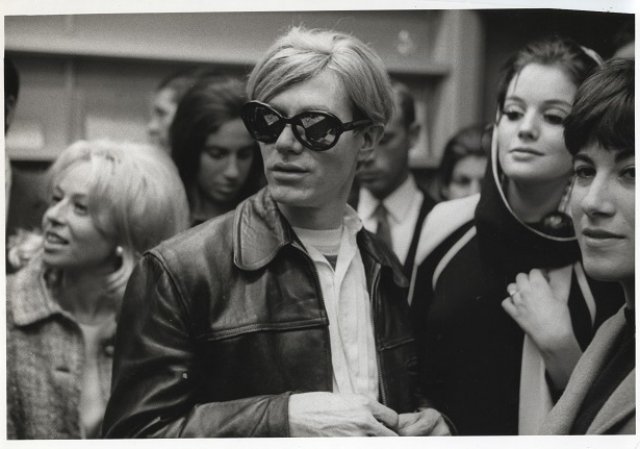

The ICA organized the second museum exhibition dedicated to Andy Warhol, with nearly 40 iconic work as well as staging a performance of the intermedia work Exploding Plastic Inevitable by Warhol and the Velvet Underground.

I967

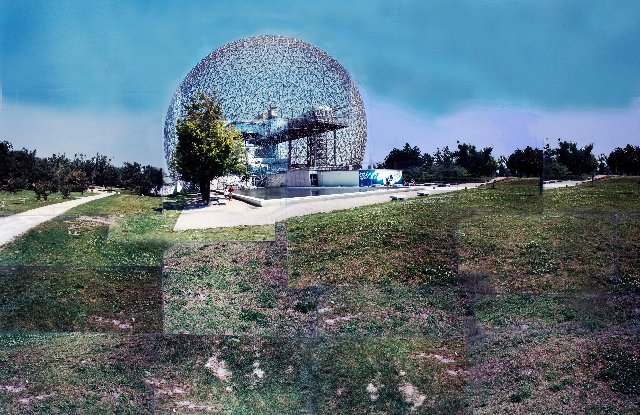

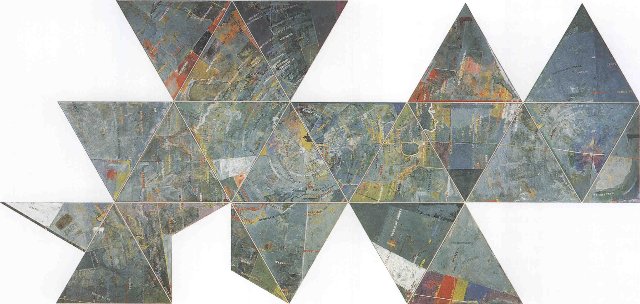

Works from the American Pavilion, a geodesic dome by Buckminster Fuller, from the Expo ’67 Montreal World Fair. It included a large Map by Jasper Johns and Firepole by James Rosenquist.

There were ambitious projects entailing public art including Robert Indiana’s iconic Love. Art in Transit entailed installing an MTA trolley in the gallery.

With her husband, the artist Harold Thurman, and their son Blair the family would relocate in 1961. They divorced while she was director but remained amicable. Blair later became the primary installer and assistant to video artist Nam June Paik. Sue and my wife Astrid Hiemer, than an administrator of MIT’s Center for Advanced Visual Studies, became best friends.

What follows are excerpts from a long series of interviews between Thurman and Robert Brown who gathered New England materials for the Archives of American Art.

Sue Thurman: The news came that Tom Messer was going to the Guggenheim, and that he would like me to be a candidate for his job here. I knew Tom fairly well through various things we had done in the profession together. The ICA had built a building, and I had seen the building because I had come here for a museum meeting, the spring that the building out on the river opened. I paid very little attention to whether that new building might have any problems or whether the institute itself might have any. And I was never misled. There was some talk of the fact that it was not an easy field, and contemporary art never is. I asked a number of questions, but as it turned out, the institute had a very distinguished past.

It was very hard to get there by the public transportation. As soon as I was here, I said, “Let’s look at attendance.” It was drastically low. The ICA was on precarious grounds as far as anyone could say…ICA never had any extensive reserves because people always said, “I won’t give you anything much because you’re not collecting art.” That was the big argument.

(Thurman began to plan programming.)

I went to Germany and made up the Julius Bissier show in the late fall and early winter of ‘62. That’s a show we had when we first got into the location in town. That’s how positive I was about the result. I was there making up a show, which would open a new location that we didn’t have yet.

Bissier was by then sort of an elderly fellow and a marvelous host, and I visited them in Switzerland and in northern Italy and then I went to all of the galleries, which were going to lend to that show.

Where we went, it turned out we didn’t know at that time. We went to the New England Life, first floor. Marvelous space and it cost a bit to get it ready to be a gallery, and get simple furnishings, and to keep the staff at work making shows.

Sue Thurman photo by Berkley Bottjer.

(Differences between Messer and Thurman.)

His style and mine are very different, but I would say that Tom, and probably rightly so, had put such an emphasis on the relationship with the artists and on the subtleties of exhibitions, and was quite a writer. Tom is a very gifted person. I think that, maybe, the last thing he would let himself think about would be—and I don’t mean this as any kind of insult—but just like the total amount we owe the creditors would not be what he would be concerned with—I mean, somebody else should do that anyway in any organization…

I have spent my entire career or nearly my entire career in nonprofit organizations. There may be a better way to what we’re doing which is educating with live art as against slides and the kind of thing that happens on a campus if you study art or in a studio, and this is a very esoteric thing. You go to Europe, you go around, you pick up all those Bissiers, you get—it’s such a unique, one-of-a-kind—even if it’s not terribly expensive, it’s terribly nerve-racking and terribly time-sensitive—it’s a very unusual kind of thing to do.

How it happens that small museums even survive has continued to amaze me; because I could see in a big one, there are always enough people. You divide up the work, and if it’s big, it means it has some substantial source of money to begin with. But in these, which have a director and some assistant, and a custodian, and a couple of guards, and nowadays a few interns, those are helping a lot. But my theory is that everything that runs that way is running on half-empty a lot of the time.

(With the Bissier show opening the Newbury Street space there was a dramatic shift.)

Traffic was amazing, and it never slowed up, the whole time we were there. We got the space on favorable terms because Kelly Anderson, who was running New England Life, was a friend of Nat Saltonstall’s. Nat was marvelous, and he was so concerned about it all. But he had given eternally to it, so he couldn’t be the one who just bailed it out forever. Nat had put together some very wonderful people, and they certainly came into play at this point. As a matter of fact, Kelly Anderson’s wife was a member of this group that initiated a thing called Gallery-Go-Round, which happened. People still do it occasionally, but this was a huge thing when it was started. We had it, I guess, about five years straight with mounted police. The blocks were all emptied so that people could draw on the street, and every gallery was open…We stayed there (Newbury Street) until, I think, ‘68, and left under very adverse circumstances having nothing to do with anything we had done…

While I was the director of the ICA, and throughout all the other directorships that I’ve read the newspapers about, I noticed that people are always somewhat puzzled, a lot of people are, as to what the ICA should be doing. I mean, whatever it’s doing, “Maybe this isn’t the right thing,” they’re always kind of saying. I think it gets in that position unavoidably because there are other museums in town, and especially now that they own a few works of contemporary art, people don’t stop and think, well would they own them if the ICA hadn’t been here encouraging this?

(Edward Kienholsz as an example of controversial programming.)

Nobody could prove to me that Ed Kienholz (1927-1994) was not a highly creative individual worth everybody’s seeing what he had made. Yet, I know that most people didn’t see Ed Kienholz’s work and never will. A small percentage—turned out to be a huge number of people when we put his show here and when it was shown in Berkeley—but compared with all the people who look at art.

There were people—I must say I didn’t think there many—who couldn’t see the worth of it or thought it was junk, or whatever. Just as you went in—I’ll give you an example of what it looked like. We had a small gallery through which you passed into the large gallery, and that was often very useful from an installation standpoint.

The big room, you could see from out on the street, so you installed the large gallery, two directionally. It’s the only place I’ve ever been where you did that. Everything you move an inch, you have to run outside and look—The Diner was really an eerie place. All of his things tended to have this little rickety kind of music going in them like a faraway radio, you know?

You couldn’t really tell what the radio was doing or why it was there, but it was adding to the sort of detachment factor—I mean detachment for practicalities. It was getting you over into the emotions. And then there would be—I think there were real aromas. I’m not sure that this was all imaginary—the aromas that maybe someone had been ill. I mean it was—it had this kind of raunchiness about it. And figures there—you would pass it, people would pass it thinking there’s nothing to see, but then it would occur to them there must be something to see, so they would go back, you know?

It was very good to see how that show rearranged people. They couldn’t do things their usual way. You passed out through a little neck of hallway and then you were in the big hall. Now, against the wall there was a piece called The Wait. And though I would have no—if I owned it, if it had been given to me, I would have no place I could put it. So, this is a kind of art that you can collect only if you have a museum of your own or you give it to a museum. In this case, that’s what happened. It went to the Whitney.

The Wait was a very sad—a sort of sweet-sour sad commentary on old age. In the middle sat a figure, which you thought was somebody’s grandmother. But when you looked back, you realized no, it’s cow bones. These were cow bones making the legs, making the arms. We read it as somebody’s grandmother, this is what he’s telling us in a way, you know, that there are many things that come out the same in our heads. We have this unrecognizable, old person. Somehow, we know it’s a woman. I think we know it’s a woman because of her kinships. She has around her neck, if I remember, beads but these are beads, which I think they have faces of children in them. Everything surrounds her that tells you about her life, and it’s all pretty horrible because you don’t even know that she is still alive. The suggestion is that she isn’t. It’s wrenching. I can’t imagine any woman or a man, but particularly any other woman, who could look at that and give it no mind. I used to go out and look at it every day. That’s one advantage to working in a museum—you can collect in your mind. That’s why I remember it so well.

Then there was the Dodge, the Back Seat Dodge, which on the West Coast, had created a bit of trouble, or people had created the trouble, the Dodge didn’t. It had lovers in the backseat, which was a part of our time as far as he was concerned. There was some talk of maybe this will be difficult or you shouldn’t have it maybe, or something. We thought that we really shouldn’t not have it. You can’t take the man’s work and then edit him out. Anyway, it’s just a part of the whole scene he’s telling us about—the neglected, aged person, the drunk in the little counter-restaurant place.

When he came we had the most wonderful time. He loved the coast of Maine. He had never spent much time there. We had a wonderful member of the institute who lent us the key to a great place right on the water on Kittery Point. We went up and had, what I remember as a high point of parties and fun. All the young people who by then worked around the ICA were richly repaid because they got to spend that wonderful, long weekend hearing the stories of Ed Kienholz and eating lobsters.

He was really a charming person, very honest, and he had a humor. He was just a wonderful person. He’s no longer living. He was raising his two children. They lived with him, and then when he would go on these trips, art trips, he was always calling his children, of course, telling them what he was doing.

(The Warhol show)

The Warhol pieces were absolutely beautiful in that big space, you know? Of course, it was all the Jackies and the flowers, the blossoms, and some of the wrecks. It really needed that kind of space. It was really beautiful, and we published a catalog. Alan Solomon by then was serving as our guest curator sometimes. See, that was one way I got around not having enough money.

RB: Warhol himself came, did he?

ST: Oh, Warhol, I think he came. You know with Warhol, you’re never sure, you were never sure. He used look-alikes. He was certainly invited here, and we assumed that it was Andy Warhol. We had a simple kind of supper down at that French café that used to be on Berkeley. There were a number of hangers-on that night and—such that I think maybe he didn’t come at all, but that’s not the issue. We had The Velvet Underground, and that performance was, of course, a big test for our audience. They found it very disturbing, a number of people did.

While that was happening, some of these people who had either followed or I think it was people that he certainly hadn’t sponsored, but they went into the restroom, the men’s restroom of that auditorium and tore the porcelain fixtures out of it just as a sort of display of mindlessness. Which was, of course, a very terrible thing to hear about because we had been good tenants, and we were very grateful for our space. We were allowed to stay there a while longer, but this certainly turned the tide as to our keeping it forever.

(Other shows)

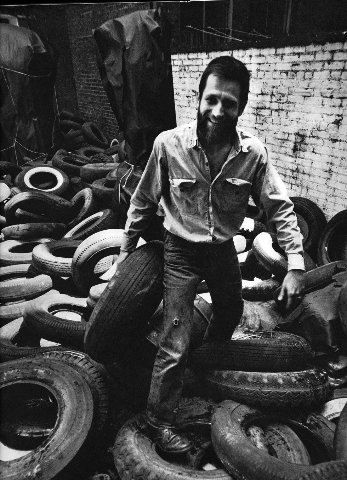

We had one called Painting Without a Brush, which may have been pushing it a little. I thought of it because I had been seeing—as you make one show, you’re always having ideas about other shows. I’d been seeing quite a few things, a surprising number of things, which were using paint and using some sort of flexible surface, often canvas but not always, and getting the paint on the canvas without a brush, doing it some other way. And part of it was a bit contrived. I remember putting in the show a work that was made by having the surface laid on the ground, and a tire with a very nice tread was driven over it in all sorts of directions. I don’t know if that’s a work that will live forever, but he got into the show, and it didn’t hurt anybody. It did show everybody that you really could give some thought to this kind of thing. There’s so much yet to be done. It is a kind of idea, kind of tweaking ideas.

I’ve lived my life, so far, on three-by-five cards, and you see them here. When things get complicated, you go to color, three-by-five cards, but you really, mostly don’t want to forget whatever it is that you want to remember. So, you just write a word down, and finally, you have a rubber band around a bunch of cards, and you have several of these sets of rubber bands.

RB: One of these sets eventually became Painting Without a Brush.

ST: Event-types of things happen. We used to bring huge audiences together in the New England Life Hall for panel discussions. Allan Kaprow came up for maybe eight weeks straight at one point when he was writing his book on happenings. On one occasion, he wrapped me in Saran Wrap and I was about to keel over. He hadn’t done this before, and he was using this as a way to get—well, make his point, whatever it was. I began to realize I wasn’t thinking clearly anymore. I saw a woman that I knew to be a doctor stand up in the audience and rush toward me. She had her surgical scissors in her purse, and she cut this off, and she said, “I know, but you’ll be all right.” We had a near miss that night but he was a person of no caution and lots of invention. He and I had gone to school together at Columbia, so, you know, I probably wouldn’t have liked it if most people had nearly smothered me.

(Funk, 1967)

{In 1967 Peter Selz organized Funk for the University of California, Berkley. Artists were asked to complete questionnaires about the funkiness of their work. The catalog quoted them. In an Art Forum review several artists pushed back on Selz. Bruce Conner dubbed Funk as “Fake.” As had been the case with his MoMA show, New Images of Man, Selz was accused of botching his subject. His effort was regarded as a sanitized version of more complex art. But it was shocking and made waves that reverberated when it traveled to the ICA.

{Boston Globe critic Edgar Driscoll was at his best covering the genteel shows of the Copley Society. He was out of his depth in a review with the headline “Funk Art is Punk Art, Splutters One Boston Matron” and ended with: “The shortest explanation of all for most of Funk is ‘Ugh!‘” A letter to the Globe suggested that similar exhibitions be curated by the Department of Sanitation.}

(Design in Transit)

ST: Someone said, “Why can’t we have an exhibition called Design in Transit?” and they said, “Oh, good.” Since they never had any idea of limiting anything, they said, “We can put a transit car right down the middle of the gallery.” Well, that sounded good to me, you know?

(That entailed a meeting with the director of New England Life to ask for permission. Thurman was allowed to remove a large window to install and deinstall an MTA trolley.)

In 1967 with overreaching ambition Thurman installed work representing the U.S.A. from Expo ’67, Montreal’s world Fair at Horticulture Hall. Then living in New York I saw the exhibition while visiting and reviewed it for Arts Magazine. At the time, I was a part time studio assistant to James Rosenquist. I saw him create the enormous Fire Pole from a snapshot. Hung from the top of Fuller’s dome it created the illusion of a giant fireman rushing to the rescue. It was thrilling to see the work in Boston. Another highlight was an enormous Map by Jasper Johns. It was speculated that she had spent money she didn’t have. Not long after her tenure ended. She later took a half time position with the New England Quilt Museum.

During the summer of 1968 the ICA closed on Newbury Street and its assets were moved to storage in its abandoned home on Soldier’s Field Road. For Avatar I wrote an article “ICA On the Run.” It was meant as an obituary. While assumed dead it would rise again as a new Mayor Kevin White took office. Kathy Kane was Deputy Mayor when White launched the city wide Summerthing. Drew Hyde, the next ICA director, worked on programming while forming bonds with Kathy, her husband Louis (founder of Au Bon Pain), and through them the Mayor.