Belinda Rathbone Part Two

Why Boston Missed the Boat on Contemporary Art

By: Charles Giuliano - Feb 16, 2015

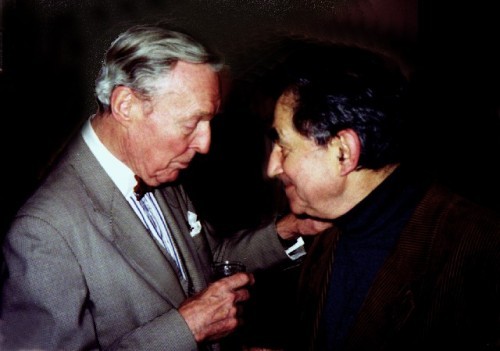

Charles Giuliano Did you put your head in a noose by writing this book? There's an easy criticism that it's an apology for your father.

Belinda Rathbone That's a very good question. I wanted to do a book about the Raphael affair but I also wanted to do a book about my father's career. It would have taken us to Detroit and St. Louis, perhaps that's the book you would have liked better, through the Depression and World War II, the South Pacific.

(Rathbone’s first job after graduating from Harvard was as assistant curator at the Detroit Institute of Arts, following that he was director of the Saint Louis Art Museum from 1940-1955, with a leave of absence during WWII when he served as US Navy lieutenant in the South Pacific BR)

It was really interesting to research all of that stuff, especially the early years.

When I came around to doing this book instead, I knew I had a double challenge. One was to find the truth through interviews and archives.

There were two bodies of concerned people; one was my father's close friends and my family. I said to them, I know it sounds weird, but we have to get to the bottom of this. Without knowing exactly what I was going to find out.

The other was the concern of my publisher that we can't have this sound like hagiography. As I said to my siblings, nobody will take this book seriously, and it will be worthless, if it just sounds like I'm apologizing.

These are the things you don't really know until the book is out and about. Even if my editor said it read well, you don't really know until it's out there for readers to decide for themselves. A lot of people tell me that they think it's really balanced.

CG It's not worth doing if there ain't risk involved. No pain no gain.

BR Well that's right. Exactly. It pained me to hear the voices of my father's detractors. It was actually more difficult to commit those words to type.

CG Including mine.

BR Yeah. Your interview was helpful because it was one of the interviews that showed me the other side that I was never exposed to. There were others like that. You showed a certain angle on it - not the trustee's angle - more the public's, the press, the artists' angle. That was very important part of the story. It gives you even more of a sense of the pressures that my father was under.

CG What I conveyed to you then and now is that I always liked Perry. I was a dissident and that was the era we lived in. Although I always found him charming and personable. Your book exposed things that I wasn't cognizant of. It presented him in a light that for me was more tolerable. Had I known these things I might have felt differently about him.

For example, I just assumed that he came from money. He seemed like a part of the old boy network. Perry had the aura and manner of a natural, privileged aristocrat. It was revealing to learn of his parents struggling to send him to Harvard when he didn't earn a scholarship. It was interesting to read about him learning to interact with the aristocratic and wealthy through the Paul Sachs seminars at Harvard. He learned protocol and how to conduct himself at black tie occasions. You sense that he schooled himself in the rules of the game. He learned more than art history from Sachs.

But you also sense that those bastards, the trustees, knew he was not one of them and treated Perry accordingly. He may have joined the Algonquin Club, and looked good in a tuxedo, but they let him know he was not one of them.

Your book conveys that he had to tread a delicate line with them.

BR That's right. I like that you say that. It's something that I couldn't say in the book.

CG I think it is in the book pretty strongly. Not directly or vehemently, but you spelled it out. Here was a self-made man from humble origins who succeeded in a complex world and rose to great social status. He enjoyed financial security and went yachting with them. He looked the part.

BR Oh yes. There is a lingering question - had he been a Brahmin, would they (the trustees) have treated him the same way regarding the Raphael?

CG How wonderful. I'm glad you said that. (both laugh)

BR This is what I couldn't say in the book. I'm saying it to you because it's an interesting question. I'm not concluding anything but just putting it out there.

CG You made it very clear that they pulled the rug out from beneath him. Wasn't he in Greece when he got the news that the trustees had panicked and handed over the painting without due process. It's likely that at most they might have had to pay a modest fine. Instead they hung him out to dry and he was fired. (Rathbone submitted his resignation in August, 1971, but on the condition that he would remain director until June, 1972.) As I read between the lines he was fired by telegram.

But I also asked myself why was Perry in Greece? What was he doing out of the office in the midst of a crisis? Why was he cruising the Mediterranean as though it was business as usual? His museum and career were on the line.

BR That's interesting. All I can say is that he took his leisure pretty seriously.

CG I love it. (both laugh)

BR Also he was very trusting. That's a big part of the story.

CG (Directors of major museums, such as Thomas Hoving and Philippe de Montebello of the Met, generally come from old money. In Great Britain those positions are held by the aristocracy. The Oxford educated Malcolm Rogers came to the MFA after he was passed over as director of London's National Portrait Gallery. During my first interview with Rogers he told me that he was descended from Midlands butchers. He was proud of being able to butcher a hog and make descent sausages but warned me not to call him the "Butcher of the MFA." Is it a slight or an oversight that he has not been knighted despite a distinguished career? If Sir Elton John and Sir Paul McCartney then why not Sir Malcolm Rogers? The MFA expansion was designed not by Sir but rather Lord Norman Foster. In Boston it seems that anyone with an Oxford education and a British accent is deemed to be a de facto aristocrat.)

Let's explore another issue. You state that Perry was anxious for the long-standing curator of paintings Constable to step down. He may have been conservative, particularly in the area of modern art, which Rathbone was eager to expand, but he made great acquisitions, including the museum's iconic masterpiece by Gauguin.

(A Tahiti period Gauguin was recently sold privately for $300 million. The sale of the 1892 oil painting, “Nafea Faa Ipoipo (When Will You Marry?),” was confirmed by the seller, Rudolf Staechelin, 62, a retired Sotheby’s executive living in Basel, Switzerland, who through a family trust owns more than 20 works in a valuable collection of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist art, including the Gauguin. The paintings has been on loan to the Kunstmuseum Basel for nearly a half-century. By that measure what would be the worth of the MFA's masterpiece "Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going?" and arguably Gauguin's greatest single work?)

BR That's right.

CG It's one of the greatest modernists masterpieces, not just for the MFA, but for any museum. It is to Boston what the great Seurat is to the Art Institute of Chicago. ("Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte," 1884)

When Perry assumed Constable's position, let's face it, he was not a curator. Other than undergraduate study at Harvard he was not a scholar. He came from training in connoisseurship and was a generalist. His consigliore, Hanns Swarzenski, was a medievalist. What were they doing making decisions about modernism? And yet, it's said that Perry made some very good modernist acquisitions.

When John Walsh was appointed he made statements that he was not the first curator of paintings since Constable. For all those years there were subordinates staffing the department with no real authority.

BR You have to understand the context of the times. A lot of museum directors were and still are involved in high level acquisitions. Tom Hoving was, and he was a medievalist. Otto Whitman at Toledo was a highly regarded director there for many, many years and I may be wrong about this but I believe that he also ran the paintings department. Now that's a smaller museum but everybody thought he did a great job. He had exactly the same training that my father did. They were classmates.

Now it's so easy for us to look back and say, What? No curator of contemporary art?! No, nobody had a curator of contemporary art. Until about 1970. It was a whole new idea. They weren't sure just how far into the present they were supposed to acquire.

CG What about Henry Geldzahler at the Met?

(July 9, 1935 – August 16, 1994. He began his career as a curator of American art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and in 1970 at the age of 33 he put together the museum's sweeping centennial exhibition, "New York Painting and Sculpture: 1940-1970," a highly personal selection of 408 works by 43 artists.)

BR He joined the Met in the department of American art. He assumed the role of contemporary curator. I can't be sure of this but I don't think he was given that title. He may never have been given that title but obviously that's what he was. In other words it was a new idea because we're talking about the 1960s.

CG You get the impression that while Perry was director of St. Louis there was more support for modern and contemporary art than he had later in Boston. Joseph Pulitzer backed him and there were other prominent and involved modernist collectors. The board in Boston didn't support his interest.

BR This is true. I'm headed for St. Louis this weekend. It's a very different town. They're very friendly out there.

CG (Both laughing) You crack me up.

BR The difference is striking. Yes. It was a smaller museum but it seemed to come more naturally to excite the community. It was possible to be a leader of that movement along with Joe Pulitzer who's your pal. Pretty soon that gets inspiring. From Germany you bring in the greatest living German artist, Max Beckmann, and introduce him into the mix. Suddenly things just start happening.

CG Would you say coming to Boston was cold water thrown in his face?

BR It really was. Certainly as far as the modern art piece went. He came with high hopes of bringing Boston up to date. He clearly put a lot of energy behind that. It was one of the reasons why he was eager for W.G. Constable to leave. Because Constable had no interest in modern art.

CG When I came along covering Boston in the late 1960s, for me and the artists I interacted with, Perry was a stick in the mud and old fogy. They liked calling him "Percy" Rathbone.

BR That's how things can change. You're the same person but the circumstances can be so different. Although it was a sidebar to the main Raphael story, I tried to show how he plunged in and tried to bring Boston up to date. Not just buying modern art, but also in putting on this really ambitious show (in 1956), European Masters of Our Time. It showed his commitment, and he hoped to inspire collectors in Boston - to attract collectors to the museum and earn their respect.

Most people don't realize that to attract collectors, (museum directors) have to demonstrate their commitment to a medium or movement. You need to do that in order to attract those gifts. If you show a lot of fashion photography you're going to be given fashion photography. If you show postcards you're going to be given a lot of postcards.

That's what's wrong with certain exhibition programs. Yeah, you want to bring people in, but what do you want in the long run? You need collectors to buy the things you want which you can't afford to buy yourself. You want collectors to admire and respect the museum for what you are doing in their field of interest.

CG We know that with one move on the chessboard a museum can have a substantial presence. When the Cone Sisters returned from Paris initially they showed the collection by appointment in their home. They never married and left their collection to the Baltimore Museum of Art. We visited a couple of years ago and other than the Cone collection it wasn't impressive.

(The collection of Gertrude Stein was broken up and dispersed by her heirs. The works were stripped from the walls of the home she shared with Alice B. Toklas who was allowed to remain in the space until her death. It reflects why there is a struggle today to seek legal status through gay marriage.)

BR I visited Baltimore recently and found that they have an outstanding collection of American art.

CG Or what Karolik did for the MFA in 19th century American art.

(Maxim Karolik (1893–1963) was an opera singer, collector and donor. He married the heiress Martha Catharine Codman (1858–1948). Karolik was guided in his purchases by the MFA, including folk art and Hudson River School paintings. )

BR Absolutely.

CG The Karolik collection extended the strength of the MFA with its depth of works by John Singleton Copley and Colonial portraits.

The Lane Collection gave them significance in early 20th century American painting and photography. This is an area the museum had snubbed prior to this gift.

(The Lane Collection, comprising more than 6,000 photographs, 100 works on paper, and 25 paintings is one of the finest private holdings of 20th-century American art in the world and encompasses an unparalleled collection of photographs. The gift includes Charles Sheeler’s entire photographic estate of nearly 2,500 works; an equal number of images by Edward Weston; and 500 photographs by Ansel Adams. It also features paintings and works on paper by major American modernists, including Arthur G. Dove, Georgia O’Keeffe, Stuart Davis, and John Marin, as well as Charles Sheeler. It includes painting by Hyman Bloom and Karl Zerbe of the Boston Expressionists which the MFA went out of its way to ignore. The gift was made to the Museum by Saundra B. Lane, who, with her late husband, William H. Lane, has been a longtime Trustee, friend, and supporter of the MFA. Rathbone initiated the MFA’s relationship with William Lane, inviting him to join the visiting committee of the Paintings Department in the 1960s.)

In that dialogue you have to also talk about the ones that got away. Perry courted Susan Morse Hilles including an exhibition of her collection with insignificant results. (Sculpture and Painting Today: Selections from the Collection of Susan Morse Hilles, Preface by Perry T. Rathbone, foreword by Susan Morse Hilles, October 7 to November 6, 1966)

BR They got some things from Hilles. I don't really know what happened. Did she give most of her collection to one museum, or did she sprinkle it around? I really don't know. You have to admit that he tried. These are questions that really deserve more research.

I did research these questions. I didn't just read my father's letters to my mother - I read his letters to her from Peggy Guggenheim's Palazzo in Venice - they were fun to read. I also went into the MFA archives and looked for the Peggy Guggenheim correspondence with my father to find out what happened there. There was traffic. It shouldn't have come as too big a surprise

(Peggy Guggenheim made several gifts of works of art to the MFA over the years, but ultimately bequeathed her collection to the Guggenheim Museum in New York BR).

If you're an important collector you can have very nice relationships with lots of museum directors.

CG My understanding is that the relationship ended abruptly because of an alleged anti Semitic remark in her presence by a representative of the MFA. It was told to me by an art historian who was present during the incident. He wishes to remain anonymous.

BR You've told me this story before. My father and Peggy Guggenheim remained friends as far as I know. He was disappointed not to get the collection, but they were never not friends.

CG It can't be verified but I have a direct source. He was in the room and heard the comment. My understanding is that she was interested in giving her collection to the MFA because she was not close to her uncle and the collection would have had more of an impact going to the MFA.

BR I don't know if there were other factors. What she now has is a monument to her memory in Venice. It's not as if the collection has just been absorbed by the (NY) Guggenheim Museum. This is where I really do not know the history, I wish I had interviewed Tom Messer before he died. I've been in touch with people who knew him. I missed that.

CG There was an ICA press conference that Messer attended. I am paraphrasing but in essence I asked him "Is it true that during your time at the ICA there was a plan to merge with the MFA as its department of modern and contemporary art?" He responded by confirming that it was true.

BR That's been documented.

CG Have you seen that document?

BR I have, in the MFA archives. There's some correspondence. It was too much of a sidebar for me to spend a lot of time on it. You don't even want to bring up something like that unless you plan to follow up with more information.

Tom Messer was director of the ICA during the time that my father was director of the MFA. The ICA at the time of this discussion was actually housed in the Museum School.

CG Yes I saw exhibitions there.

BR You did? Amazing!

CG I may be wrong but I think I saw a deKooning show.

(The founding ICA director was James Plaut, supported by Nat Saltonstall. The ICA moved, to the Metropolitan Boston Arts Center, located at 1175 Soldiers Field Road, which was designed by the museums founder, Nathaniel Saltonstall. The newly built, modernist glass enclosed gallery was 80 feet long and 33 feet wide and was raised 12 feet off the ground on steel supports. Initially, Messer programmed there. I vividly recall seeing the first American exhibition of the Austrian Expressionist Egon Schiele when I was a teenager. Messer moved the ICA to the second floor of the Museum School. When Messer left for the Guggenheim the ICA, under Sue Thurman, moved to New England Life Hall on Newbury Street. The ICA was evicted at the end of her adventurous tenure. The belongings of the ICA, including an important library, were put into storage in the Brighton building.

The ICA was near extinction. After a summer of working with Mayor Kevin White and Summerthing, supported by Louis and Kathy Kane (then Deputy Mayor), the decision was made to re-launch the ICA in Brighton. The ICA also programmed a gallery, now city council office space, in the new Boston City Hall. Working with Mayor White the ICA was moved to the Parkman House on Beacon Hill. Hyde left and there was an interim term by Chris Cook on leave from the Addison Gallery. Hyde returned briefly and again with the help of the Mayor, found a new home for the ICA in a former jail next to a fire station on Boylston Street. After several directors Jill Medvedow oversaw the design and construction of its current waterfront home.)

If you look at the taste for the arts in Boston the interest was always more Germanic than French. That includes Perry and his relationship with Max Beckmann. He collected in that area. Consider the important expressionist works of the Busch Reisinger Museum that were acquired as a statement of anti fascism.

The question is, what was Rathbone's role in rejecting a merger with Messer and the ICA? Did Perry want to keep modernism to himself? Was there a tension between them? Did Messer see that there was better opportunity in New York? He joined the Guggenheim in 1961 not long after it completed its Wright building on Fifth Avenue. It was not then the global institution it would later become under Tom Krens.

BR I have no personal recollection of Perry ever speaking of a merger of the ICA with the MFA. I know of him loving the ICA and having a lively relationship with it. Through my research I know that he was a great admirer of Tom Messer. He considered them to be good friends.

CG It's important to note that Messer advised the MFA on some key acquisitions.

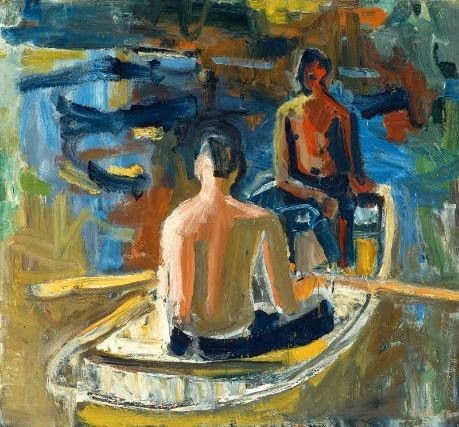

("Willem Sandberg" 1956 by Karel Appel (Dutch, 1921–2006) 130.2 x 81 cm, acquisition 1961. David Park "Rowboat"1958. David Park (March 17, 1911 – September 20, 1960) was born in Boston but became a key member of the Bay Area Figure Painters. It's a wonderful painting that is rarely shown at the MFA. Those two acquisitions give a sense of what Messer might have accomplished for the MFA. By definition the ICA did not collect. That has resulted in Boston having little or no depth in Post War American art until former curator Ken Moffett focused on formalism and color field painting in the 1970s.)

BR I haven't seen it (Park) in a long time.

CG One senses that having Messer involved in those acquisitions may have been an overture to having a larger relationship with the MFA.

BR I have no idea. No matter what (my father) might have thought about that, it would not have been his decision - it would have been a board decision. He may have advocated a position, but he couldn't possibly have made that decision alone. If at the time it seemed that (the MFA and the ICA) could have served each other's needs, I for one, in the long run, doubt that it would have been a good idea.

Look at the ICA now. It's finally on its feet. It's thriving and has a very distinct role apart from the MFA. And it’s a good thing it does.

CG There were clashes between Jill Medvedow, present director of the ICA, and Malcolm Rogers because they were both fundraising at the same time. They were pursuing the same donor base. The mantra has been "we don't want to interfere with the good work of the ICA."

(An exception occurred in 1988 when David Ross and his ICA staff collaborated with Ted Stebbins and Amy Lighthill of the MFA to curate the American half of The BiNational: Art of the Late '80s in cooperation with the Stadtische Kunsthalle and the Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen of Dusseldorf.

Lighthill was fired and replaced by Kathy Halbreich recruited by Alan Shestack from The List Visual Arts Center at MIT. She soon left to take over as director of the Walker Arts Center. Her assistant, Trevor Fairbrother was elevated to the position of curator. When he left Rogers appointed Cheryl Brutvan who eventually was dismissed. After founding contemporary curator Ken Moffett, other then the brief tenure of Halberich, the MFA, until now, has lacked a notable head for that department. It is a part of why the modern and contemporary collections fall well below the standards for major American museums.

Edward Saywell is the current chair of the Linde Family Wing for Contemporary Art of the Museum of Fine Arts. There are reasons to be optimistic but with little hope of recovering from decades of misdirection and neglect. Of course the interesting question is what might have been if a strong department and collection strategy had been initiated by Thomas Messer.

As a kunsthalle the ICA opted not to collect. Only recently has it changed that policy. During its decades of instability, had the ICA collected, there was no adequate space to display and store those acquisitions.)

BR Exactly.

CG During those years the MFA missed the boat on collecting. As you comment, if they don't show modern and contemporary art, there isn't the base of collectors to donate works to the museum.

Back in the day if you came into by the Fenway entrance and turned to the right there was a gallery dedicated to 20th century art. But what was in there? Works by Donald Stoltenberg, Fannie Hillsmith, Loren Maciver and an enormous green abstraction. ("Rue Gauguet" Nicolas de Staël, 1949). When I asked Perry about that painting he said that it was purchased for around $6,000 and was then worth a lot more. But please. What was that all about?

BR I remember Calder in that gallery. Also a Brancusi - "Golden Fish" - which was stolen and melted for its alleged gold. It was in fact made of bronze. The gallery was ever changing and works were not necessarily a part of the permanent collection. A group of Picasso's collaged sculptures "Bathers" was one of those long-term loans.

At least there was something. This was the gallery my father established almost as soon as he arrived (in 1955). There was at least a place where people could find modern and contemporary art in the museum.

CG In one of their European jaunts Perry and Hanns had lunch with Picasso in 1963. They came home from his studio with "Rape of the Sabine Women."

BR The first Picasso painting acquired by the MFA my father bought in the 1950s. It's almost cubist. ("Standing Figure," 1908 acquired in 1958). It was the first (Picasso painting) acquired for the museum and the first for my father, well before "Rape of the Sabine Women."

I never personally loved that painting but, by the way, there's a whole new generation of people who feel differently about Picasso's late work.

CG Jan Fontein told me that, because the Guggenheim borrowed the painting for a show of the late Picasso. Frankly, I think it's all crap. Read John Berger ("The Success and Failure of Picasso") to know why.

BR That's why we need another generation to come along who aren't formed by the same prejudices.

Interview Part One.

Review of Belinda Rathbone's The Boston Raphael.

Malcolm Rogers on Contemporary Art.

Thomas Messer former ICA director Archives of American ART

DeCordova Museum's Painting in Boston.

Chawky Frenn's 100 Boston Painters.

Belinda Rathbone Boston Globe op ed piece, February 22, 2015