The Boston Athenaeum: All Shook Up

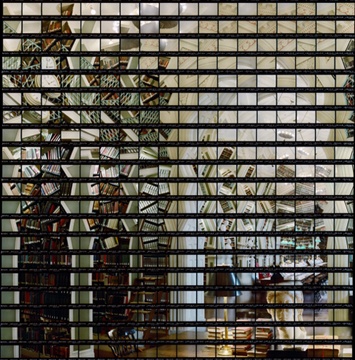

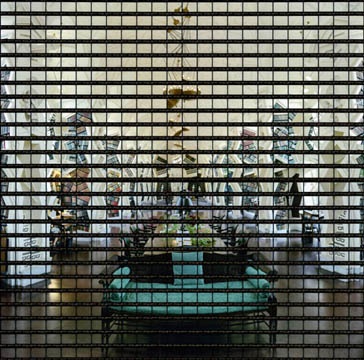

Photographs by Thomas Kellner

By: Erica H. Adams - Feb 18, 2008

"All Shook Up" is an exhibition of photographs as beautiful as Byzantine mosaic rocked by an earthquake; no reference to Elvis Presley. German artist-in-residence (2006) Thomas Kellner's photographs deconstruct the Boston Athenaeum, a bastion of Brahmin culture founded in 1807 as a 'reading room, library, a museum and laboratory'. Known for photographing world monuments, Kellner's first interior is the Athenaeum's newly renovated space. On view from February 13 – April 19, 2008 at 10 1/2 Beacon Street, in the Boston Athenaeum's first floor, the full color catalogue of All Shook Up includes an introductory essay by Richard Wendorf.

Thomas Kellner (Bonn 1966) deploys world monuments and the Athenaeum's interior, deconstructed in service of some unknown utopia. Each photograph's intractable base rises-up in a quivering frenzy of architectural fragments suspended in air like 'frozen music' as architecture was called by German philosopher Goethe. Monuments in Kellner's hands become a liquid architecture.

A painter by training, the first monument Kellner photographed was the Eiffel tower (1889) inspired by Robert Delaunay's faceted painting of this Parisian tourist destination. Delaunay's simultaneity of form, similar to Kellner's fractured photographs, is he said, more Orphist than Cubist. Orphism emphasized lyrical color instead of Cubism's austere intellectualism of form.

In 1996, Kellner's career began when he attempted to photograph the entire border of re-unified Germany with a pin-hole camera –all 3,728 miles or 6,000 kilometers of it. Unable 'figure out how to do it" he made a pin-hole camera with 11 pin-holes that recorded 11 images on a single negative strip. Ultimately, this led to Kellner's technique for constructing photographs.

Total constructions, Kellner literally builds his photographs of architecture: each room is rendered in successive rows that rise up from a stable base. Each row is formed from a single filmstrip of entire roll of film. Moving from left to right, Kellner takes incremental shots across a room's expanse. The angle of each frame 'shot' is calculated in his preparatory drawings on a grid: the horizontal base is rendered as [ - - -] while upper elevations are diagonal [ / / ]. These suggest a rooted body and mobile mind. Kellner admits he often loses track of where he is on the upper patterns.

Where David Hockney's early 1980's Polaroid collages of peopled interiors are emotional and handmade Kellner's architectures dissemble political structures and are photographic 'hybrids': at the 'intersection of analog and digital film' Kellner uses an industrial scanner to record and unify his rows of film strips then, digitally printed. The final image reveals what usually is not printed –frame numbers and sprocket holes –a practice used in much Sixties 'personal' documentary film to underline the media's construction and question its factuality. The black frame heightens colors similar to how black lead lines enclose stained glass and allows the image to float as an apparition.

Structure has been the subject of much German photography from the 35 year study of plants by Karl Blossfeld (1892-1957) that appear like cast metal sculptures to August Sander's (1876-1964) cross-section of society during the Weimar Republic. Recently, Bernd Becher (1931-07) and his wife Hilla Becher (b. 1932) catalogued industrial buildings including water towers later translated by their students, Thomas Ruff (b. 1958) Andreas Gursky (b. 1955) Candida Hofer (b. 1944) and, Thomas Ruff (b. 1954) frontal mapping of faces and institutional interiors. Kellner grew-up, he said, between the town where August Sander (1876-1964) photographed and in the village whose houses were the first subject of the Bechers.

Thomas Kellner's vibrant work commemorates a turning point in U.S. history when dissembled monuments, social structures and their economies are on the brink of momentous change. The Boston Athenaeum has added Kellner's work to its contemporary photography collection. Currently, also on view are photographs by Peter Vanderwarker and Shelburne Thurber. Before renovations, Richard Cheek photographed what's considered one of the most handsome spaces in America. As renovations began, Thurber, known for her wistful odes to abandoned spaces, documented the Athenaeum's appearance, in the "Fifth Floor with Rolled-Up Rug". Post-renovation, Vanderwarker's Athenaeum is a light filled sanctuary of learning whose extreme symmetry was purposely softened in the rennovation. The Athenaeum's collection of sculpture and paintings, in part transferred to the new Museum of Fine Arts, Boston in 1876, still includes Boston based painters often in Europe John Singer Sargent, and Washington Allston alongside life-long South End resident, African American painter Allen Crite.

http://www.bostonathenaeum.org/