Michelangelo's David-Apollo at the National Gallery

Unfinished Sculpture on View Through March 3

By: Charles Giuliano - Feb 18, 2013

The Muzeo Nazionale del Bargello in Florence displays many works by Michelangelo Buonarotti (1475-1564) including most famously his monumental David.

It is viewed in a niche at the end of a corridor flanked by a number of unfinished works depicting Captives which were intended for the artist's monumental tomb comissioned by Pope Julius 11.

When his patron died the new pope, Leo X, ordered the artist to create tombs for his family members Giuliano and Lorenzo di Medici in Florence.

Unlike artists of his era who employed assistants to create aspects of major commissions Michelangelo worked entirely on his own. While there were assistants every stroke of paint in the Sistine Chapel or carving of his many sculptures reveal the hand and unique touch of the artist.

Although he created drawings and studies for his projects he had a different approach to sculpture. Unlike other sculptors it does not appear that he made clay sketches. A number of these bozzetti by Bernini were recently shown at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

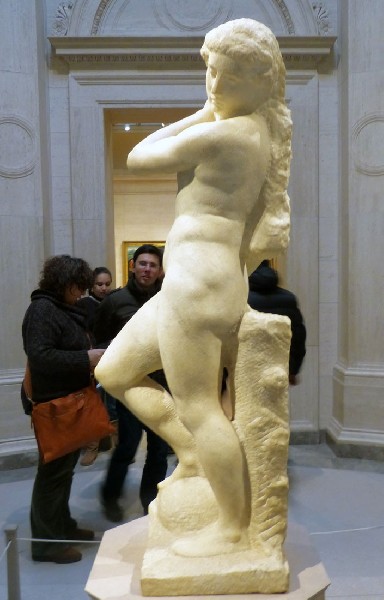

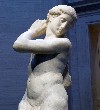

Consistent with the philosophy of Neo Platonism he liberated the soul of the figure in the block of marble. This process is decribed in his sonnets and is abudantly evident in the many unfinished sculptures, such as the Apollo-David, on view at the National Gallery through March 3.

The torsion of the figure with its gesture of reaching over a shoulder suggests the tension of a David about to unleash his iconic slingshot and bring down the giant Goliath. The pose evokes the later version by Bernini.

The completed monumental sculpture reveals the young David in repose seemingly having completed his task. There is often an eroticism associated with images of the young David most notably in the sexy version by Donatello which predates Michelangelo's.

The work now on view in Washington has unfinished aspects, enough to reveal the process of the artist, but is near to completion.

Of the Captives for the Julius Tomb one must visit the Louvre to view the two fininished pieces the Captive Slave and the Bound Slave. They provide a sense of what the works in the Bargello might have looked like had they been completed. The groups of Captives were intended to surround the base of a monument with Julius II on its top. The four corners of the monument were intended to include Biblical figures. The completed Moses is the single work from the aborted project which is a part of the actual, modest tomb of the pope.

The pose of the unfininished 1530 sculpture resembles a David but this is speculative. So there is the second possibility that it is an Apollo.

The first and most famous David was carved in 1501 when the artist was just 26. The 1530 work seen at the National Gallery suggests that he returned to the subject some three dacades later. Compared to that first work, which established the career of the artist, this later sculpture is far less ambitious in scale, energy, and uniqueness of vision.

Perhaps it is an afterthought and is arguably not a part of the artist's canon of major works.

That said any occasion to see an original work by one of the greatest masters is cause for celebration.

Press Release of the National Gallery Follows.

The National Gallery of Art,presents 2013—The Year of Italian Culture by unveiling Michelangelo's David-Apollo, which will be on view in the West Building's Italian galleries through March 3, 2013. First displayed at the Gallery in 1949, this rare marble statue from the Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence, is now among the renowned masterpieces—ranging from classical and Renaissance to baroque and contemporary—that Italy is bringing to some 70 U.S. museums and cultural institutions in 2013. The Gallery will also display The Dying Gaul (1st or 2nd century AD) from the Capitoline Museum, from October 2013 through February 2014, as part of The Dream of Rome, a project initiated by the mayor of Rome to exhibit timeless masterpieces in the United States from 2011 to 2014.

2013—The Year of Italian Culture is a project launched by Giulio Terzi di Sant'Agata under the auspices of the President of the Italian Republic, Giorgio Napolitano. This program will showcase the best of Italian arts and culture in some 70 U.S. cultural institutions across America in more than 40 major cities, including Boston, Chicago, Detroit, Houston, Los Angeles, Miami, New York, Philadelphia, San Francisco, and Washington. The initiative will highlight research, discovery, and innovation in Italian culture and identity, focusing on art, music, theater, cinema, literature, science, design, fashion, and cuisine.

The David-Apollo first visited the National Gallery of Art more than 60 years ago, as a token of gratitude for postwar aid and to reaffirm the friendship and cultural ties that link the peoples of Italy and the United States. The masterpiece's installation here in 1949 coincided with Harry Truman's inaugural reception. During the next six months the sculpture was seen by more than 791,000 visitors. In 2013, a new generation of visitors to the National Mall around the time of another inauguration—Barack Obama's second—will also have the chance to view the David-Apollo.

"With Michelangelo's David-Apollo, we are thrilled to continue the Gallery's tradition of showcasing the art of Italy in the nation's capital," said Earl A. Powell III, director, National Gallery of Art. "The Gallery has a rich and enduring relationship with the people and culture of Italy. We are home to noted Italian sculptures and drawings, as well as one of the most important collections of Italian paintings in the United States—including the only painting by Leonardo da Vinci in the Americas: Ginevra de' Benci (c. 1474/1478). We have hosted more than 80 exhibitions featuring such international loans, and we are proud to serve as the opening venue for 2013—The Year of Italian Culture."

"My country's cultural heritage is a unique 'natural resource,'" said Giulio Terzi di Sant'Agata. "Culture is what immediately comes to mind when you think about Italy. It is indeed a fundamental pillar of our foreign policy. In this spirit we launch the year of Italian culture in the United States in 2013, which will include an impressive program of events in the arts, science, and technology. This initiative will enhance the friendship between Italy and the United States and forge a new legacy for future generations."

Exhibition Organization and Support

Under the auspices of the President of the Italian Republic, the presentation of Michelangelo's David-Apollo inaugurates 2013—The Year of Italian Culture, organized by The Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Embassy of Italy in Washington, in collaboration with the Ministero per i Beni e le Attività Culturali and with the support of the Corporate Ambassadors Intesa Sanpaolo and Eni.

The presentation has been organized by the National Gallery of Art, Washington, The Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Embassy of Italy in Washington, the Soprintendenza Speciale per il Patrimonio Storico, Artistico ed Etnoantropologico e per il Polo Museale della città di Firenze, and the Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence.

Michelangelo's David-Apollo

The ideal of the multitalented Renaissance man came to life in Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475–1564), whose achievements in sculpture, painting, architecture, and poetry are legendary. The subject of this statue, like its form, is unresolved. In 1550 Michelangelo's biographer Giorgio Vasari described the figure as "an Apollo who draws an arrow from his quiver," referring to the classical god of music and enlightenment, whose arrows could assail both terrible monsters and disrespectful mortals. A 1553 inventory of the collection of Duke Cosimo I de' Medici, however, calls the work "an incomplete David by Buonarroti." By then it had entered the Palazzo Vecchio (the seat of government in Florence), joining several earlier sculptures of the biblical giant-killer David, a favorite Florentine symbol of resistance to tyranny.

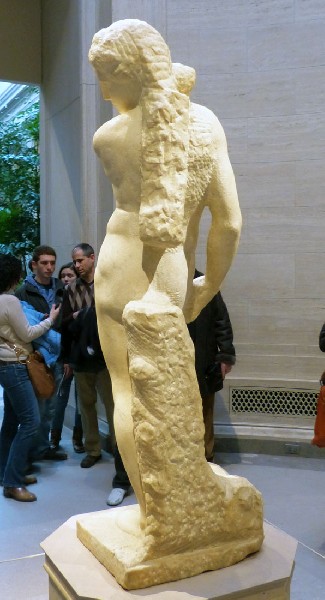

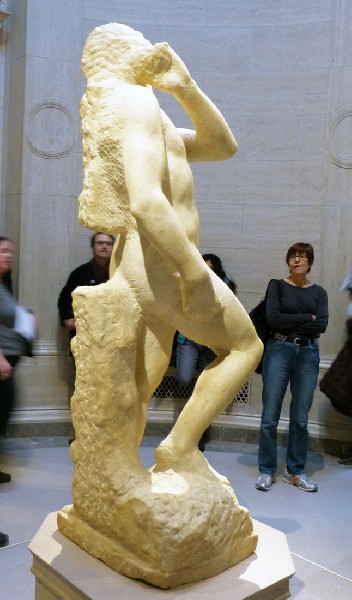

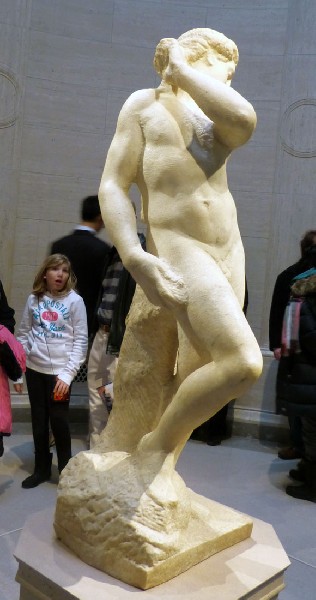

In the David-Apollo, the undefined form below the right foot plays a key role in the composition. It raises the foot, so that the knee bends and the hips and shoulders shift into a twisting movement, with the left arm reaching across the chest and the face turning in the opposite direction. This spiraling pose, called serpentinata (serpentine), invites viewers to move around the figure and admire it from every angle. Michelangelo's conceptions of figures in this complex, twisting pose exerted a strong influence on contemporary and later artists. Although he brought the David-Apollo almost to completion, he left the flesh areas unfinished, as though veiled by a fine network of chisel marks that would have been filed off when the sculpture was completed. Least finished are the supporting tree trunk and the elements that would establish the subject: the rectangle on the figure's back that could become a quiver or sling, and the form under his right foot that could be a stone or the head of the vanquished Goliath.

Michelangelo was carving the David-Apollo for Baccio Valori, who was appointed interim governor of Florence by the Medici pope Clement VII in 1530 after the heads of the Medici family and their imperial allies had crushed a resurgence of the republic. Having fought on the republican side, Michelangelo sought to make peace with the Medici. One way to accomplish that goal was by pleasing their agent Valori, for whom the artist worked on this sculpture and on a palace design. He brought the figure tantalizingly close to completion before leaving Florence, never to return, after the death of Clement VII, his patron and protector, in 1534. Valori, who later joined a failed rebellion against the Medici, was executed in 1537, and Duke Cosimo I de' Medici took possession of the statue.

Related Programs and Offerings

An illustrated brochure written by Alison Luchs, curator of early European sculpture, will accompany the exhibition. Luchs will also present a public lecture entitled "Michelangelo's David-Apollo: An Offer He Couldn't Refuse," on January 27 at 2:00 p.m. in the East Building Auditorium. Eric Denker, senior lecturer, will lead Gallery Talks about the sculpture at noon on January 3, 5, 7, and 9 in the West Building.

Pina Ragionieri, director of Casa Buonarroti, will give an overview of the Florentine museum's remarkable collection of Michelangelo's work. The lecture will take place at the Embassy of Italy in Washington on February 11 at 3:00 p.m.

2013—The Year of Italian Culture in the United States

Research, discovery, and innovation will be highlighted through Italian art, music, theater, cinema, literature, science, design, fashion, and cuisine. Nicola Piovani, winner of the 1998 Oscar for Best Original Dramatic Score of the Roberto Benigni film La vita è bella (Life is Beautiful), has composed a musical score dedicated to this yearlong event. The celebration also coincides with the 200th anniversary of Giuseppe Verdi's birth, which will be honored with performances featuring Riccardo Muti, conductor and musical director of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, and classical pianist Maurizio Pollini. Visitors to American museums and cultural venues will be able to view great masterpieces by Michelangelo, Caravaggio, Morandi, Chia, and De Chirico, among others.