The Dishwasher Dialogues, Groping for Light

Secrets of the Cave

By: Greg Light and Rafael Mahdavi - Feb 18, 2026

Rafael: It was a little hazardous going down to the cave or coming up the steep stairs from the basement, lugging up the cases of beer and wine. I would place a table by the trap door in the floor so nobody would fall down the steps and end up in the hospital. In the dark my fingers groped for the light switch. The fluos lit up, and I was in Leroy’s treasure den. Years and years of collecting wines that nobody ever drank. I think Leroy just bought them because he could. He himself rarely touched the stuff. He was a hard liquor man, as I said before. Thousands of bottles, red and white and rosé wines, from all over Europe, mainly France, Italy, and Spain.

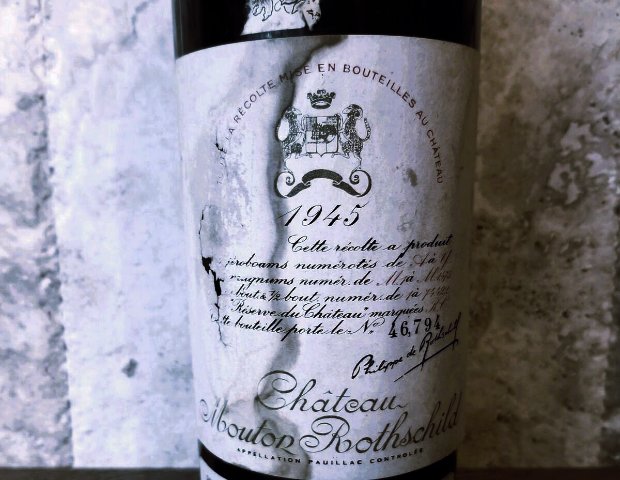

Greg: La cave was a world unto itself. In hindsight, I wish I had explored it more than I did. Of course, I had searched through the different boxes and shelves for vintage wines listed on the menu, but so rarely ordered. To begin with I had no idea where to look. I remember even Leroy had to hunt a bit, for a special guest, or a special event. Sometimes he would suddenly surface and serve us a twenty-five-year-old Chateaux Mouton Rothchild of some description (the 1945?) for Thanksgiving or Christmas dinner. It tasted wonderful because of the story he added about how rare it was and when, where, and how he came by it. Would it taste any better today, after 45 years of enjoying wine? I don’t think so. Not without the story. But I think I would enjoy la cave more. I would have a better appreciation for the wide variety of vintages and dates that he kept down there.

At twenty-five when my experience of alcohol was still rigidly stuck in the narrow domain of beer—actually, just cold lager—subtle distinctions between different wines were beyond me. The red, white, rose division I quickly mastered. I liked red, tolerated white and hated rose. And sparkling anything (especially Champagne) was simply grotesque. I did immediately appreciate the simplicity and the excellence of the Chez Haynes Reserve; red, dry and 13F a bottle. Rumored to be satisfactory by the day-to-day client, but not worthy of a swish and a sip by the aficionado. Even the inexperienced, self-described enthusiast looked down on it with contempt, unless furtively served in a glass with the suggestion that it was a unique and ancient selection from the darker corners of Leroy’s collection. Then its taste blossomed.

Rafael: I can’t help butting in here.

Greg: Butt away. That’s the essence of a dialogue.

Rafael: Leroy once said you can drive around the country, and search for small little known vignobles, and taste and search and retaste, until you’re blue in the face, but the best rule of thumb is always this: if it’s expensive it’s very probably very good. That was also Astrid’s advice to smart-ass clients.

Greg: So, not the timeworn wine rule of thumb: ‘the older the wine, the better’. Which is the only decree about wine that I carried to France with me. And which got me into some trouble. The local Louis Max wine merchant who sold us much of our wine, gave me a real-world lesson in wine myth. He came through the door just after 5 p.m. on December 30th, 1977, just as he had on many other occasions, and casually sold me 12 cases of Beaujolais Nouveau. I had resisted because we were not running low. ‘Buy it now’, he told me. ‘The next batch will be next year’s vintage’. Despite the glaring clue in the name, he persuaded me with the ‘age’ myth. How was I supposed to know that Beaujolais Nouveau needed to be consumed in the year the grapes were picked? I had essentially purchased 144 bottles of undrinkable swill. When Leroy went down into the cave that day or the next, he was apoplectic. “What fucking idiot bought all this?” he shouted up the stairs. Leroy never let me forget that mistake. It took me years to sell it all––mainly to American and English tourists who knew less about wine than I did.

Rafael: There was the lingo that went with wine tasting. We heard it often enough from wine lovers––oenophiles sounds better, eh?

Greg: Sounds rather grotesque and creepy if I am to be honest.

Rafael: The men tried to impress the ladies. We on the staff just raised our eyes and said ‘oh, oh, another major bullshitter’. Few simply said, ‘ahh, c’est un excellent vin’. Oh no, most of them had to embellish with comments about le bouquet, la robe, les larmes, la belle attaque, la couleur, and tra-la-la. There were champagnes too, but they weren’t that old, as vintage bottles kept a maximum of ten years. That’s what Leroy told me one evening when he came down to the cave and opened the freezer.

Greg: The freezer? He was in search of his special vintage.

Rafael: The freezer was a big box about the size of a single bed. It was empty or nearly empty. In the corner was a frosty, brown block of something, the size of a brick. ‘Give me the axe there in the corner, will you please,’ Leroy told me. He took the block out of the freezer and placed it on the floor. He swung the axe downward, and a small piece came away from the frozen block, about the size of an ice cube. Leroy put the block back in the freezer and slammed the door down. He picked up the piece from the floor.

“What is it?” I asked.

“Hash,” he said, “my hash stash.”

Greg: That was his secret Chez Haynes reserve. But it was not for sale. I don’t remember him often sharing it. We had to get our own.

Rafael: After the wines, champagnes, and the beers, I took up the hard stuff, new bottles of the good liquor, single malts and blended. And middling quality booze, Teachers, Black and White, Grants. I simply refilled the bottles. If I ran out of one, I filled it up with another, same stuff, on different brand bottles. When Leroy went on a binge, I knew precisely what he drank. I became an expert with whiskies. When I ordered a scotch at another bar, I could tell after the first sip if the drink was watered down. And most bars water the scotch down. Leroy’s cave wasn’t my domain, but it felt like it. I would sit on the lower steps and imagine what an excellent hiding place this could be. There was a door, well encrusted in the brick wall, behind the pastis bottles. I never asked Leroy where it led. Did anybody ever hide from the police here? How about during the war and the German occupation? Anybody die down here? Was anybody ever conceived here?

Greg: La cave did stimulate beyond its stimulants. Even in the middle of a search for a particular wine, it demanded you stop for a quick moment and look around. In the longer moments, after restocking and before dinner, you sometimes got to dream.

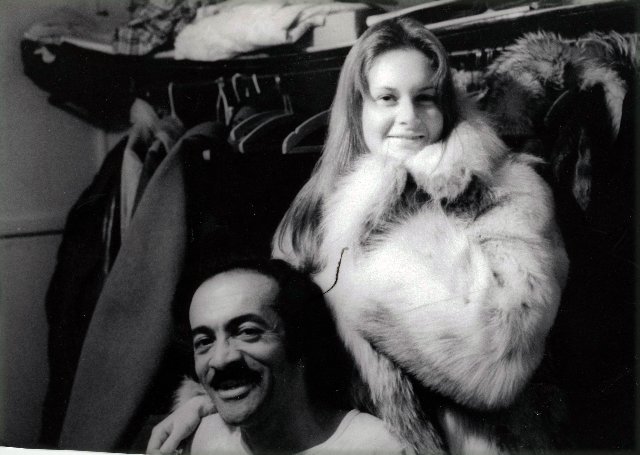

Rafael: For dreaming there was also the cloakroom. It was to the left, at the back of the restaurant, after table five, right before you entered the kitchen. Sometimes when one of us was exhausted from partying the night before he or she would slink off to the cloakroom and take a snooze during the staff dinner. There was no bed in there, not even a tiny couch. Still, there always seemed to be some boxes or sacks or mysterious bundles handily plopped down or propped up to make a welcoming place for a quickie nap before work, especially on Saturday nights when Pigalle was jumping.

Greg: A snooze in the cloakroom after a Don dinner, and a long day surviving Paris, was a welcome reprieve. Even better late at night when the kitchen was quiet, and the guests were dithering over their cigarettes and coffee. It was a brief diversion from the kitchen, even if it was just sitting on a box, leaning back into the softest coat one could reach. Those experiences should be in Paris guidebooks, up there with a stroll across Pont Neuf, a croque monsieur in the Latin Quarter, or a glass of wine on any café terrace in the city.

Rafael: The cloakroom was never empty, and apart from the junk that accumulated there, we found coats and scarves and gloves, and even a pair of trousers. Those pieces of clothing stayed there, sometimes for months on end, until somebody would come and ask if, by any chance, we had kept this or that. Once I found a bra and a pair of expensive high-heeled shoes. The lady must have walked out wearing only her stockings and raincoat. We were all sure that a few people had made love back there, but none of us saw anybody having sex there. Another thing I remember is that the cloakroom smelled nice. I can only explain it by the perfumes that lingered among the coats and scarves.

Greg: The odor was distinctive. That was partly due to its location next to the corridor leading to the kitchen. Not that the contrast with the myriad odors of the kitchen, wafting down the corridor, picking up the strong dark espresso machine aromas, was horrible. On many nights the combination was a delight; earthy, real, down to earth (pick your adjective), whereas the cloakroom was of another place and time. It took the lives of the clientele and concentrated it into a pleasurable, carefree out-on-the-town fragrance with just a hint of sex. And cigarette smoke (not quite the grotesque fiend it is currently).

Rafael: I remember that I was nearly always a little tired, hungry, and cold. Nowadays some would quickly say, oh that’s because you’re not eating right, or you lack this or that vitamin, you should get your thyroid checked, you have low blood sugar. I didn’t check anything.

Greg: Regretfully, I don’t think I took more than a couple of snoozes in the cloakroom: not like today when naps come fast and thick and are rarely perfumed.

Rafael: I was lucky, I was healthy, doing a hundred other things besides bartending at night in Pigalle.

Greg: Every night was late and often stimulant-enhanced. Every morning was early (relatively speaking) to get a start on the real work of the day. It was a good thing we were young.

Rafael: Much heavier tiredness invaded my body when I became a father. Feeding the baby in the middle of the night, emergency runs to the hospital, laundry, and more laundry, teething, fevers, and more. That was real fatigue, and it lasted the first ten years of my children’s lives. That was normal. I don’t care what people tell you, and if they tell you otherwise, they’re lying.

Greg: What sane parent would tell you otherwise?

Rafael: One of us would gently shake the snoozer in the cloakroom awake at five to seven, give her or him a cup of coffee right before the first clients walked through the saloon doors. Leroy knew about these catnaps before work, and he didn’t mind. It is hard to imagine this easy-going attitude in a restaurant today, where every penny is counted in a computer and magically ends up in another computer in London or Shanghai. At Chez Haynes, employees had no precise job description, and we didn’t have to punch into a computerized clock the moment we arrived. And when an accident happened, when I cut my finger on a broken glass, I knew somebody could take over the bar, and one of the waitresses would clean and bandage up my palm and Leroy, or Don would say, here, have some cognac, it’ll help.

Greg: Yes, back to la cave once more for treatment. The cave was our Lourdes.