The Real McCoy

With Tyner Back When

By: Charles Giuliano - Feb 23, 2010

During the recent performance of jazz pianist, Mc Coy Tyner and his trio, at the Mahaiwe Performing Arts Center in Great Barrington, it was shocking to note how he has aged. He was born in 1938 . It was a struggle to hear and comprehend his raspy, hoarse comments to the audience.

Looking under the piano I admired his slick alligator kicks. It was moving to watch him slowly make his way off stage at the end of the set. He told us "See you another time" but you wondered just when, and where that might be.

In the time since the Mahaiwe performance I have been dwelling on the memory of an afternoon with Tyner, in 1979, when we were in our prime. We are about the same age. It is how I had always thought of him until looking at those recent publicity shots and hardly recognizing him.

Experiencing the performance, evaluating and writing about it, and these further reflections have evoked deeply rooted feelings. Most of what I know about jazz, and the arts in general, comes from interviews and conversations down through the decades.

Perhaps it started when I was an adolescent. My uncle James Flynn took my sister and me to Storyville to hear the Duke Ellington Band. It was the 1950s and everything about the experiences is so rooted in me. The club was painted in tones and patterns of black, brown and beige. Later I would learn that was a famous Ellington suite. The waitresses and patrons were also black and white. That was probably my first such experience. And that band. My goodness. Immediately I was intrigued by the horns, Harry Carney and his enormous baritone, the sweet lyrical alto of Johnny Hodges, those high trumpet notes from Cat Anderson, Ray Nance alternating between trumpet and violin, the thunderous percussion of Sam Woodyard.

My uncle loved the Duke. During intermission he chatted with Ellington and insisted on introducing us. Jim said something that embarrassed me at the time. He mentioned to Duke that I was a rock and roll fan.

After that night I wanted to know everything about the Duke. I collected and devoured his records. Still do. There was another great interest in Louis Armstrong. Particularly his Hot Five and Hot Seven recordings.

There were even occasional gigs. I remember one with Ellington sponsored by the Sisters of Hadassah at Gloucester High School. The ladies, wearing fancy dresses with corsages, took turns thanking each other. It went on and on. Finally this woman said "And, with no further ado, Duke Ellington." The curtains parted. After a long applause the Duke paused, looked out at us, and simply said "I'm speechless."

Years later I interviewed him in a suite at the Eliot Hotel. He had a gig across the street at Paul's Mall. Approaching the suite there was a ruckus and a screaming woman. She and some luggage were being tossed into the hall. The door was open and I entered saying "Duke, Duke."

He emerged wearing a dressing robe and a do rag. We sat on the couch. He opened the conversation by stating in that autocratic, elegant manner "People can be so rude." I asked what he was up to and he said "Writing about my favorite topic, me." After awhile he looked at how much I had written and asked if I had enough? Then said "I have to put my head on some feathers."

You never know what to expect. During a dinner with Rahsaan Roland Kirk, a blind musician with the ability to play three horns simultaneously, he went off on a screed. The band members snickered as he expounded on the mo fo white jazz critics. During an elevator ride with Gerry Mulligan he went off on me about the ambient muzak. How some musician was getting ripped off. Moments before he had answered the door of his room and the woman inside was not his wife. During a Miles Davis interview he spent the entire time combing his hair and looking at me in the mirror. Sheeeeeet.

There were also hilarious moments like meeting Tiny Tim. What a trip. Hunkered down with Moondog or Jimi Hendrix in Times Square flea bag hotels. Elton John opening the door of his hotel room dripping wet with a towel around his waist. Stan Kenton ranting about how "Kids Music" (The Beatles) got him bounced from Capitol Records.

Memories. Well, perhaps, there is no fool like an old fool. Once when I was lecturing to students about social conscience a kid said "Oh, Mr. Giuliano, you're so Joan Baez."

Digging into the archive I unearthed the McCoy Tyner folder. There were some negatives, a few prints, a yellowed clipping from Sweet Potato, a long gone music rag, and the original draft of that interview. It was published in October, 1979. It is unusual to hold on to an edited draft but in this case it is fortunate. It seems that, probably for space, the editor cut a number of quotes. They are restored here.

During the Mahaiwe gig there were no offers to meet with the media. Even performance photography was strictly limited. The artist has the right to limit access. At this point in his career Tyner has little need for publicity. Unless 60 Minutes makes the call and we no longer have the wonderful Ed Bradley to conduct the interview. And the jive ass local scribes and mo fo honkey jazz critics (To quote Rahsaan and Miles) ask the same dumb questions.

Three decades ago, however, Tyner provided a gracious and fascinating interview. Of course I wanted to know about his years, as a very young artist, with John Coltrane. It is no doubt what writers still ask when they get the chance.

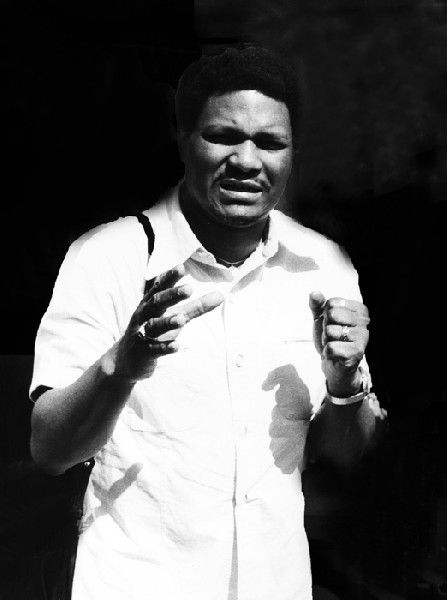

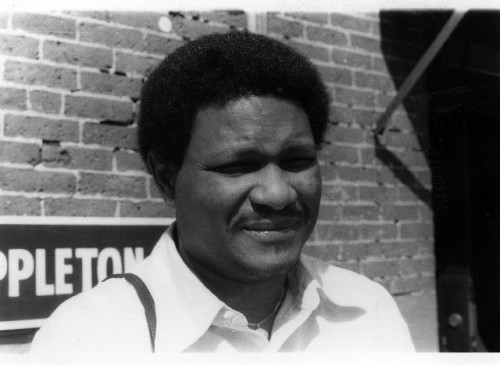

We were in our prime, mid career, with miles to go before we sleep. I recall, and the images I shot that day attest, that McCoy was a handsome, powerful, vigorous man. It went along with the persona and style of a very physical style of playing. Then, as now, he attacked the keyboard.

It was a fall afternoon at Lulu White's. It is always strange to visit clubs during daylight hours. It's where the vampires sleep awaiting sundown to haunt and howl. Back then I didn't seem much sunlight and a girlfriend called me Dracula.

We talked about how Coltrane replaced Sonny Rollins in the Miles Davis group from '55 to '57. Initially fans compared him unfavorably to Sonny. Miles heard something in Trane which was still developing.

'You really can't compare Sonny to John" he said. "John was from the South and later lived in Philly, whereas, Sonny was on the scene in New York. It took John longer to emerge as a major figure."

He discussed growing up in Philadelphia with musicians including Archie Shepp, Lee Morgan, Bobby Timmons, Benny Golson, and Bud Powell. Just the year before Tyner had been on a tour organized by Milestone Records that included Rollins and bass player Ron Carter.

The breakup with Coltrane was difficult but he was generous in stating that "John was like a big brother to me. I was just 17 when I joined his group. At that time he was in his 30's so a lot of what I know and stand for comes from working with him and growing up in the group. But it goes beyond that. He knew my family and we had many friends in common. There was a wonderful scene in Philly then. There was all kinds of music being played and many opportunities for young musicians that don't seem to exist today. You can't learn this music in school. You can learn the theory but the only way you learn is to play. There were all kinds of combos that jammed and played at parties. The word would get out and everyone would fall by the session. That was also true in New York during the days of Birdland. A guy could show up as an unknown, sit in, and overnight everyone would know what he could do. Those kinds of things were happening that don't exist today."

Like some black families, because of the importance of church music, they owned a piano. "I remember one time that someone came to me and said that there was a jazz musician in the neighborhood looking for a piano to practice on. It turned out to be Bud Powell. At that time he was in poor health and only came by a couple of times. But his influence on me was strong. While I was growing up my nickname was Bud Monk because I was such a cross between them. What I admired in Bud was his incredible sense of dynamics." From Monk he derived those clusters and blocks of chords with a choppy attack.

This evolved into what with Coltrane was referred to as walls and sheets of sound. "That wall of sound idea is just what one guy wrote when he tried to describe the music" Tyner said "I don't like to limit myself to those terms. John was looking for the right musicians to put together a particular sound. When I first heard him play there were just fragments of what was to develop but I knew it was there. I could really see the potential. So a lot of the sound came as the group was put together. What was important was an effort to reach a total group sound.

"(Bass players) Jimmy Garrison and Paul Chambers were great supportive musicians. They could really get behind and drive a soloist. Elvin (Jones) was a loud and forceful drummer. At first it was too much for people. But for John it had started when he was still with Miles. He would take off on longer and longer solos. The patrons got really restless. There were instances where promoters or night club owners tried to cut him off. They were blinking lights trying to get him to play shorter solos.

"But John kept on pushing. He was a highly experimental and spontaneous artist. He would try anything that promised to be interesting. We were constantly doing things differently. He played so hard. I can remember a time in San Francisco when he burst a blood vessel in his nose. I tried to tell him to slow down but music was 85% of his life. It was everything and he just eventually burned out."

Tyner described Coltrane as a "very spiritual person who gave everything he had to his music. His grandfather was a minister and he had a strong religious sense. In order to make this music we were playing we had to be in touch with a higher power. Personally I have always been a believer in a spiritual presence."

While they were working at a club in New York, in 1965, Tyner left the group. It was difficult for him to talk about it. "At that time solos were getting longer and longer and the total sound was getting very loud. When John stretched out he would say 'Take a walk.' I was off stage more and more. I was jammed in between two drummers and I couldn't hear what I was playing. When I went to John about it he said 'That's what I'm hearing now.' "

Eventually Tyner went off on his own as did Elvin Jones. "A group is only as good as its collective sound" he said. "Each member has to be sensitive to what the others are doing. Everyone has to make a contribution to the total sound. If one member is trying to overwhelm everyone else they don't belong in that group."

When Tyner left Coltrane they saw each other only occasionally over the next two years before he died in 1967 at 41. While Trane was like a brother there was sibling rivalry.

"Coltrane was the only young musician of his generation who didn't try to sound like Charlie Parker" he said. "Bird's influence was so pervasive that everyone was taking up alto sax. Even John played alto initially. But right away John started to explore on his own. Because he didn't sound like anything people were familiar with at first people put him down. The New Yorker critic Whitney Balliett wrote about him as a 'student of Sonny Rollins.' John had the power of conviction. He believed in himself."

That's what it takes.