Malcolm Rogers Resignation Sidebar

Transition of Perry T. Rathbone to Merrill Reuppel

By: Charles Giuliano - Mar 02, 2014

The original Museum of Fine Arts opened its doors to the public on July 4, 1876, the nation's centennial. Built in Copley Square, the MFA was then home to 5,600 works of art. Over the next several years, the collection and number of visitors grew exponentially, and in 1909 the Museum moved to its current home on Huntington Avenue.

The official centennial year for the MFA was celebrated in 1970.

Prior to Malcolm Rogers, now resigning after some 19 years, the longest serving and most popular director was Perry T. Rathbone (July 3, 1911 - Jan. 15th, 2000). His tenure, 1955-1972, ended with a scandal about the acquisition of an alleged portrait by Raphael which after an investigation and global media attention was returned to Italy. Apparently, it languishes in storage.

It was a black mark on an otherwise impeccable career. This fall a biography by his daughter, Belinda, a distinguished scholar will argue for a reassessment of the many ways in which he represented a transition of the museum from a stuffy, class-conscious, Brahmin institution to the populist one today.

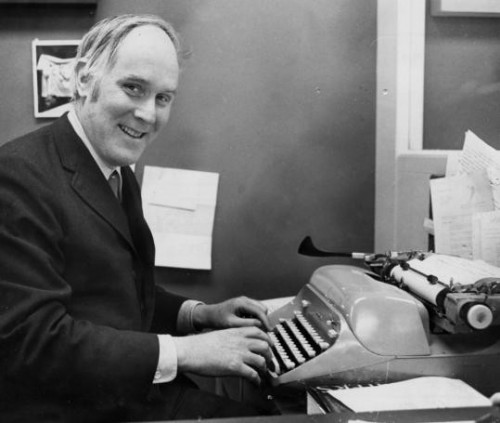

Robert Taylor (1925-2009) covered the story which apparently his paper, the Boston Globe, refused to publish. He also wrote the Sunday feature in the Globe which brought down the brief regime of Merrill Reuppel resulting from a cabal which I wrote about in the coverage of the Rogers resignation.

The Rogers story was written under the pressure of deadline. This is followup research that further confirms and clarifies a complex sequence of events. What follows is a verbatim excerpt of an interview, in the public domain and published here for the first time, from an interview between Taylor and Robert Brown then operating the New England regional office of the Archive of American Art in Washington, D.C.

Working out of an office on Beacon Hill Brown made heroic efforts to gather archival materials and conduct oral research with artists and prominent members of the fine arts community. Many including myself, contributed primary source materials.

Unfortunately the New England office was closed and through funding issues much of the material he gathered has yet to be transcribed and cataloged. It leaves many in the arts, including myself, with concerns about how archival materials will be handled by executors of our estates.

We look forward to Belinda's book, the first since the 1970, Walter Muir Whitehill Museum of Fine Arts, Boston: A Centennial History (2 Volumes) to add a new chapter to that rich institutional history. There are a diminishing number of critics, curators, artists and scholar left to tell the tales of a complex museum with its extraordinary cultural legacy. And its impact on the visual arts in Boston.

ROBERT BROWN: Do you think he thought, was Perry then somewhat of a community spirit?

ROBERT TAYLOR: Yes, and I think we all regarded him this way, and I still would. I think that he was very community minded. But the problem, from a journalistic point of view, was that you couldn't feel that way about art that was going on. I found out about this story, you know, with the Raphael right away. I went to, again it was just before I was covering art for the Globe. I was working for them, but not covering art.

ROBERT BROWN: And some informer called the paper, or called you, or?

ROBERT TAYLOR: Ah, yeah, somebody at the Tavern Club as a matter of fact and told me about it. (The Tavern Club, 4 Boylston Place in downtown Boston, Massachusetts, is a private social club established in 1884.) That's a jungle telegraph down there. They told me this and I went to the then- arts editor of the Globe and he wouldn't print it, on the grounds that you could do this because it was bad for the community. He sat on one of that committees in fact at the MFA, which would be a real conflict of interest, but he quashed the story. We didn't run that story until it had gotten out of hand. I couldn't get to (Tom) Winship (Globe editor) with the story because there was a chain of command at the newspaper. I mean, even if you know that these things are happening, that the excessioning (sic) is happening, in those days you couldn't. Of course, you can now. I mean, it would

ROBERT TAYLOR (sic): ....be the first kind of thing, because art is regarded journalistically today. It would be the first thing that would happen. But no, he effectively quashed it and sat on it and I just gave up. But then, Tom Winship, also a member of the Tavern Club, heard the same rumor, and said, "What are we doing about Perry Rathbone? You know, he's been strip- searched at customs, you know, and what's going on here?" Well, what was going on was out of hand by then, so we ran the story. I don't think Perry, of course, was very happy with it. But, it's like anything else, you develop relationships if you're covering something exclusively and you hate to do this. I think he probably regarded it as a betrayal. There was no other way of handling it.

ROBERT BROWN: And when you went and talked with Siviero (the investigator) in Rome, that must have underlined the severity of this thing, sort of no nonsense.

ROBERT TAYLOR: Yeah. He was a policeman who wanted his Raphael back.

ROBERT BROWN: Right.

ROBERT TAYLOR: And who would have willingly had the two of them (Rathbone and Hans Swarzenski) prosecuted had he been able to do so, but it did go back to Italy anyway.

ROBERT BROWN: You ran, in fact, some expensive (sic) stories on it back then at that time.

ROBERT TAYLOR: Yes, at that time. I was forced to resort, as I recall, even before when I knew about it...there was a magazine called Bostonian and I was forced to do it in this magazine because I couldn't get it into the Globe.

ROBERT BROWN: Did it become a fairly big story through that magazine?

ROBERT TAYLOR: Well, by the time the magazine, see magazines have a long lead time. [RT laughs] By the time it [the story] appeared, it was all over the place.

ROBERT BROWN: When you had it in the Globe, when Winship and the Globe broke the news, or had it been broken elsewhere as well?

ROBERT TAYLOR: I think it had been broken in the Times of London, because, I've forgotten, somebody from the Courtauld Institute had done an extensive piece about the history of the painting. Then, they sent Peter Hobkirk and their investigative reporters down to Italy and Switzerland to look into all this, and found out about the Bossi connection and Perry and Hans Swarzenski and the other things. So the whole thing came out in a rather unsavory way.

ROBERT BROWN: What was the impact of your stories immediately?

ROBERT TAYLOR: Well, I don't think the...I don't think our stories had the...I mean it was simply to inform the public of what was going on. But, the impact of it was, well, as you know, Perry resigned not long after that. But I don't think that was the impact of our stories. That was the impact of a cumulate (sic) of stories that were happening everywhere, in the New York Times and in the American press.

ROBERT BROWN: Well then you did follow then I guess what followed, the denouement of Perry's resignation and so forth.

ROBERT TAYLOR: Yeah, and then came Reuppel after that.

ROBERT BROWN: And you were involved, rather, on top of the search for a successor to Perry?

ROBERT TAYLOR: Um hmm. Well, I didn't know about that until later on. Of course, Cornelius Vermeule filled in for about eight months.

ROBERT BROWN: The curator of classical art.

ROBERT TAYLOR: Yes, as the director. Then, Merrill Reuppel came in and there was no reason for us to have any kind of vendetta against Reupell. I mean, he came in from Texas and so forth. In fact, George Seybolt had taken me to breakfast at the Harvard Club, along with the art editor who would quash the story on the Museum.

ROBERT BROWN: Was this (Edgar) Driscoll, the art editor?

ROBERT TAYLOR: No, this was Greg MacDonald. He served on the education committee and was strongly in favor of promoting the museum, which I think a laudable ambition, but you can't, it doesn't create any critical ground. Anyway, Seybolt had me to breakfast at the Harvard Club, and I know why he had me for breakfast, because I knew it then--because he wanted to leak to the Globe the news of Reuppel's arrival on the scene. Well, fine, if he wanted to do that, it was okay with me because I assumed he would do this again with subsequent stories that went on. Well, Reuppel of course was...he then proceeded into his tenure with the museum. He was obviously George Seybolt's man in the museum and he was there. As I recall, the powers that be at that point were

ROBERT TAYLOR: Seybolt and John Coolidge and maybe Nelly, I think was there at that time. Suddenly, we started getting all these stories from curators about the way in which the museum was being run by Reuppel. These things first came in as complaints, then you start getting phone calls from people who presumably are in the scene somewhere, and you're forced to follow up on them. And in this case the accusation was being made against Reuppel that he was running the museum like the ham company--the Armour Ham Company--whatever company--"

ROBERT BROWN: Deviled Ham Company. (The Underwood company of Belmont's Baker family.)

ROBERT TAYLOR: They had, the curators had for example been all herded into an auditorium where they saw a new movie on deviled ham and how it's made. Now, this is Cornelius' report to me, and Jan Fontein had his bags packed and was prepared to go back to the Rijksmuseum. There was unrest in the museum, to put it mildly. So, we ran a series that said essentially that, because this had been leaked again to us.

We found that in the course of this, while we were preparing it, Seybolt had short-circuited the search committee that the museum had sent out because he happened to like Reuppel who was in town for an art director's and museum director's convention, and who had come up to the Museum of Fine Arts and had spoken with Seybolt who happened to be in. After twenty minutes, he decided he was the man for the job. In fact, he said this on tape, and we had the tape. That is, we had the tape until Otile McManus, who was working on the story

ROBERT TAYLOR (sic): with me, decided that she'd have to go down to Dallas to see what Reuppel's reputation was in Dallas. She grabbed the tape and it was the tape with Seybolt on it. [RT laughs] She erased the tape! I had to, for subsequent six or seven months, say that this did indeed exist, that we have it. Of course Seybolt knew it existed, but we could not produce any evidence because the tape had been erased. It was like Watergate that was occurring about the same time.

ROBERT BROWN: Well, your having--there was no problem with your having the tape for the time being, was there?

ROBERT TAYLOR: He wanted us to surrender the tape; we wouldn't surrender the

tape.

ROBERT BROWN: Oh, I see.

ROBERT TAYLOR: We wouldn't surrender the tape because we said it contained this damning admission. Now, he knew damn well that it did too. But, on the other hand, he wanted the tape and by that time, we had erased the tape. We had no way of backing up our allegations when that happened. I had heard it once, and he said this, and of course we had sent a reporter up to interview Seybolt at the museum, and he was saying, "No, you shouldn't say anything against Merrill Reuppel because, you know, he's one of the most dynamic men in the museum world today." Then, he explained why he was dynamic. He had come, from the time he had first set eyes on Reupell that he had known this after twenty minutes. Well, all you had to do was to put this together with the search committee

ROBERT TAYLOR: which was then going around and interviewing people, to see

what happened.

ROBERT BROWN: Looks dynamic to me [both men laugh].

ROBERT TAYLOR: Yep, yes.

END OF INTERVIEW

Addendum from Dallas Art History by Sam Blain, Chapman Kelley's Memoirs, Chapter 5

"Suddenly, Reuppel vanished from Dallas without any official museum explanation. In time we learned that he had been named director of the prestigious Museum of Fine Art, Boston. According to the Boston Globe newspaper, Reuppel immediately offended that museum’s curators and others.

"A year or so later I received a phone call from Boston Globe reporter Otile McManus. She asked me if I knew of Merrill Reuppel. I told her I did and invited her to visit Dallas to learn more, which she did. I introduced her to various art world figures and arranged for Ed Bearden, a DMFA senior staff member, to take her into the museum’s basement storage area to view the still unannounced and still unexhibited (at the time about nine years had gone by since Jim Clark had donated them to the DMFA) alleged works by 19th century French painter Henri Fantin-Latour. So the key to this mystery was that art collector James Clark had donated these dubious paintings in order to take a $40,000 U.S. federal income tax deduction as if the works were authentic. Apparently Reuppel accepted the two “Fantin-Latours,” definitely not to exhibit them, but for other reasons, perhaps for Clark to take advantage of a big federal income tax deduction, what else could it be?

"Jim Clark admitted to reporter McManus that he had in fact claimed a federal income tax deduction and that he knew the artwork’s authenticity was questionable.

"This and much else was revealed by the Boston Globe in its March 7 and 19, 1975 newspaper editions and an article appeared in Time Magazine. The Tuesday, June 10, 1975 Globe headline stated, “MUSEUM TRUSTEES FIRE REUPPEL.” And on the same day, in the New York Times, “BOSTON MUSEUM OUSTS DIRECTOR,” a blunt term I had never before or ever since seen printed about a museum director’s leave-taking.

The Taylor transcript is in the public domain and may be used without permission. Quotes and excerpts must be cited as follows: Oral history interview with Robert Taylor, 1980 Mar. 13-1990 June 7, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.