Andris Nelsons Collaborates with BSO

Beautiful Tone, Dynamic Range and Story Telling

By: Susan Hall - Mar 03, 2017

Boston Symphony Orchestra

Conducted byAndris Nelsons

Bejun Mehta, Countertenor

Lorelei Ensemble

Beth Willer, Artistic Director

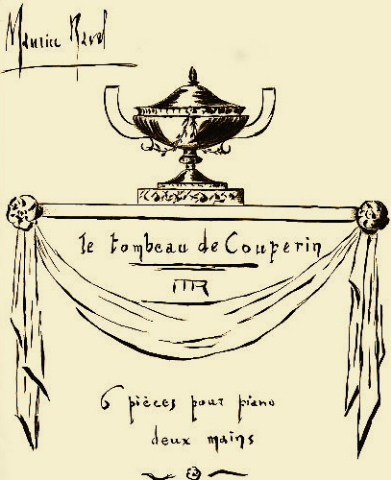

Ravel Le Tombeau de Couperin

George Benjamin Dream of a Song

Berlioz Symphonie Fantastique

Carnegie Hall

New York, New York

March 2, 2017

When Andris Nelsons stepped on to the Carnegie Hall stage on March 17, 2011 as the last minute substitute for James Levine, we did not know that the event would be as momentous as Leonard Bernstein's last minute substitution for an ailing Bruno Walter. Who knows how these seminal moments will be ranked in musical history. So much lies before the young conductor. Performance after performance Nelsons and his musician collaborators from the Boston Symphony exceed themselves.

A remarkable tone now lofts from the musicians. To call it 'lovely' is in part to recognize its quality. Yet harsh moments and high drama are also achieved. Perhaps singularity of texture, created by an unusually successful blending of instruments when the full orchestra plays, is a better description. Happy artists bow together, and that makes all the difference.

This is in no way to de-emphasize the solo playing of strings, brass and percussion and the oboe’s extraordinary performance in Ravel’s Le Tombeau de Couperin.

Striking were the extremely soft and quiet entrances at the beginning of a section or phrase. Berlioz' markings on his score do not suggest such an extreme, but the barely audible whispers which often begin a passage as Nelsons conducts add immeasurably to the listener's pleasure.

Nelsons now brings music from a dark silence. This provides a chance for both audience and performers to distinguish between the world apart from music and then enter a composer's world with ears bent in to the notes, carefully receiving the music’s message. It also offers an opportunity for the orchestra to make dramatic sound escalations even more dramatic. Nelsons is especially effective in making the dramatic differentiation. Riccardo Muti also elicits music from this distinctive silence. Out of silence and into tone.

Nelsons’ springing arms remind us of his mentor Mariss Jansons, who also often starts with a startle. Eyebrows raised, arms expectant, hovering before a note is played and then dashing in, either very quiet or sometimes loud. In gesture and musicality, Nelsons pays homage to Jansons and the years he spent observing and talking with his teacher. The effect is electrifying.

Story telling is another of Nelsons' strengths. He is a talented conductor of opera and will be at the Metropolitan Opera next year for David McVicar's new production of Tosca starring the conductor's wife, Kristine Opolais.

Ravel wrote Le Tombeau de Couperin as an homage to his musical predecessors and also as a tribute to friends who had died in service during the war. It is a gentle war memorial. From drawings and photographs by combatants we viscerally absorb the horrors of this war. So suddenly we are hearing almost romantic pictures of combatants. How did this happen?

The Boston Symphony makes the music about memory, not combat. The men honored are evoked, not the gruesome and tragic moments of their deaths. Ravel has borrowed graceful forms of the baroque dance suite. A forlane bursts out from a Northern Italian dance. Ravel's Menuet gives the oboe a prominent role, in which John Ferrillo shone. The Rigaudon that concludes the suite is an old dance from Provence which the Symphony executed with panache.

The New York premier of a composition by George Benjamin, Dream of the Song, was co-commissioned by the BSO. It is based on Andalucian texts from the 11th and 20th centuries. This layering of past and present is a hallmark of Benjamin’s work.

The extraordinary countertenor Bejun Mehta sang in the purest of tones. Yet he expresses the sense of every syllable. Benjamin’s sound world projects from the orchestra and a lustrous play between instruments and voices is brought forth. In what seems at first an erratic and frenzied opening titled ‘The Pen, ’ a remarkably dense texture emerges. Still the horns cut through the intricate web of string sounds. Mehta’s florid notes sung on just one syllable of text suggest Benjamin’s operatic style.

Pairing of texts in Dream of a Song creates a strange poetic space, expressed beautifully in the final movement. The soloist and the Lorelei Ensemble each offer a vision of dawn, but the visions were written a thousand years apart.

Topping off the evening with the Symphonie Fantastique was fantastic. Never has a would-be wife suffered so under a composer's pen. Murder is the least of it. Here too the Boston Symphony provided subtle differences in the broad sweep of a drug-induced vision of unrequited passion. Chaos of the fantastic was solidly grounded in symphonic form.

Nelson's left the audience silent and then rollicking in its appreciation. As the audience applauds, he moves to congratulate individual members of the orchestra, and the last image of him is at the very back of the stage putting orchestra members front and forward.

We are witness to the very early stages of a career. Appetites are whetted for the near and distance future. Boston at last has a music director and conductor is deserves.