Shostakovich by a Nose at the Met

William Kentridge Designs a Masterpiece

By: Susan Hall - Mar 08, 2010

The Nose

By Dimitri Shostakovich

Conducted by Valery Gergiev

Production by William Kentridge

Produced in collaboration with Festival Aix-en-Provence and Opera National de Lyon, France

Featuring Paulo Szot, Andre Popov, Gordon Gietz

The Metropolitan Opera

New York City

A stunning and apt production of Dmitri Shostakovich's The Nose has arrived at the Metropolitan Opera in New York. It will be difficult to imagine another take on this opera after viewing the creation of William Kentridge.

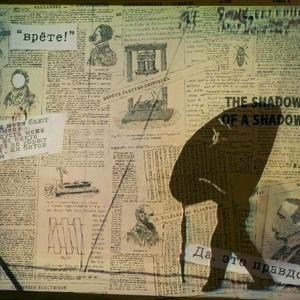

The Nose was greeted by critics in Stalinist Russia as a trip up a blind alley. It entails the diaspora of a nose which has detached from a minor Russian official's face. The opera had sixteen productions in Russia and vanished. One critic noted a new musical language based on rhythm and timbre, rather than arias and cantilenas, everyday speech is set in music. The musical leap forward from Shostakovich's first symphony was gigantic.

Shostakovich picked the Gogol story, sensing The Nose was powerful and could easily be recast as opera. The colorful language of the text made it possible to musicalize. This production takes Shostakovich at his word, pulling together many layers as an integrated production that excites, delights and surprises.

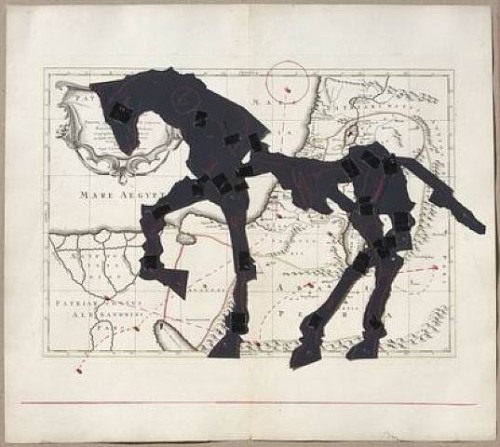

The stop-animation horse that crosses the set,on a projected screen, charms. We have a chance to look carefully because Kentridge offers images as though he were flipping slowly through an Eadweard Muybridge stop motion. The technique forces the eye to notice.

A cat featured in one of Kentridge's eight minute films takes hold of your eyes and heart, just like the wonderful, stop motion, gaited horse. In addition to Muybridge's work, the horse suggests horses of statuary, on which tyrants are seated and then torn down by the public when revolution prevails. The horse also hints that the opera is a Trojan horse, the hidden vehicle for liberation.

Russian officials had tweaked Tosca into acceptability by changing the location from Rome to revolutionary Paris. By the time The Nose was composed, the revolution was frozen in place and the party line was rigidly enforced. Between the composition of The Nose, and the 14th Symphony, Shostakovich worked with his hands tied.

Kentridge notes that this brutal comedy is a reflection of the evanescence of life, but his touch on heavy subject matter is light throughout. He captures Shostakovich's wit.

Processions are a theme Kentridge uses often in his own work. In his native South African, they depict people going to work and also marching to protest Apartheid, which dominated the society as he grew up. Here, we are traveling across Stalinist Russia after that missing nose. What fun the walking nose is, and other masked papier mache characters.

Casting Paulo Szot was a stroke of genius. His baritone is strong and clear and his talent as an actor has been noted by a Tony Award for his role in South Pacific on Broadway..

What a trip into dynamics and timber we take. The opera opens with a sneeze from the orchestra, and between acts two and three there is a 'batterie'', a percussion section in which we hear the piccolo snare drum, snare drum, bass drum, cymbals, triangle, tom-tom, tam-tam, castanets and xylophone.

Rare is the occasion when a soprano stands and delivers from a balcony that Kentridge pops onto the scene. A very conventional balcony matches one of the few conventional arias in the opera. It is beautifully rendered.

Using a premier artist to create staged performance is not a new idea. Pablo Picasso, Leon Bakst, Joan Miro, Salvador Dali, and Andre Derain all produced sets and costumes for Sergei Diaghilev's Ballet Russe. Appropriated footage in The Nose includes Anna Pavlova dancing with the Nose superimposed.

Does William Kentridge belong in the company of Diaghilev's famous modernist collaborators? For an answer consider his exhibit at the Museum of Modern Art through May 17. .

In a New Yorker essay on Kentridge, Calvin Tomkins wrote that when a teacher showed her class an eight minute Kentridge stop action animation, students could not describe what they had seen. They were stunned and awed. Kentridge has, until now, found it difficult to work in oil paint, but instead of limiting him, this intensifies his graphic and film work.

His sets for the opera are original and powerful. Type flies across the screen and is embedded in costumes. Delicate Klee lines scrawl with the music. Miro objects dance, and, of course, there is that Muybridge stop action. You don't have to get any of these references to enjoy The Nose, but the appropriations and references are interesting.

This is Shostavoich's and Kentridge's show. Valery Gergiev conducts the orchestra with careful attention to the composer's intent. The singers are all acting in the loss of the nose, the search and the final outcome, which, in the spirit of the evening, we leave to surprise.

Szot sings compellingly for 120 minutes. He is a perfect Kovalyov. Andrei Popov, Barbara Dever and Erin Morley stand out in their roles, but the whole cast singing 90 roles is wonderful. You don't notice that large portions of the Gogol text are declaimed or sung as arioso, and entr'acte musical interludes shroud the action.

Wit, parody of traditional forms like folk music, a church chorus and grotesque gallops are all on display. March is not called the month of madness for nothing. I am going to try The Nose again with a child in hand. Among other things, the production startles and delights, not just kid's stuff, of course.