Otto Dix at Neue Galerie and Montreal MFA

Among Best Exhibitions of 2010

By: Charles Giuliano - Mar 18, 2010

Otto Dix

Curated by and Editor of Catalogue: Olaf Peter

Neue Galerie, New York

March 11 to August 30, 2010

The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts

September 24, 2010 to January 2, 2011

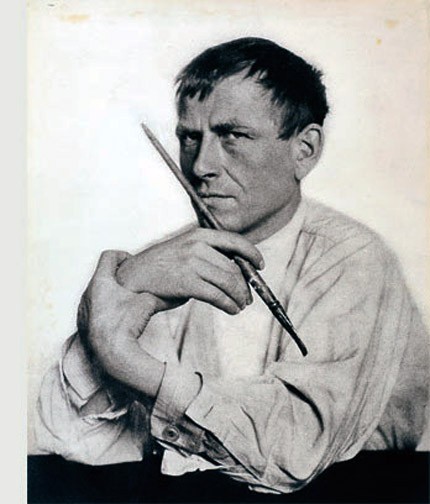

Over many decades we have encountered, and been riveted by, the occasional painting by the German artist (Wilhelm Heinrich) Otto Dix (1891-1969).

There is that single, remarkable “Portrait of the Journalist Sylvia von Harden” (1926) in the Musee National d’art Moderne in Paris. It is such a powerful image and one of the few works by German artists in a collection with a primary focus on French art. There is a large installation of works by Joseph Beuys, in this context, the “other” German artist of note.

Similarly, when the collection of the Museum of Modern Art was founded in the 1930s it had a strong bias for French art. Compared to its renowned depth in Picasso, Matisse, Cubism and Surrealism, there is just a spattering of German Expressionism and a sample of the Russian Avant-garde.

By contrast, there was a stronger interest in Germanic art in Boston. When the Boston Museum of Modern Art broke with New York, and renamed itself as the Boston Institute of Contemporary Art, it was often the first to show German/Austrian artists, including Oskar Kokoschka, under founding director, James Plaut, and later, Egon Schiele, when Thomas Messer was director before leaving for the Guggenheim.

Unfortunately, by definition as a kunsthalle, the ICA, until very recently, did not collect.

Harvard University founded the Busch Reisinger Museum with a concentration on Germanic art. When the Nazis auctioned prime examples of Expressionism, in Switzerland, Harvard came to acquire masterpieces including “Self Portrait as a Smoker” by Max Beckmann.

Even the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, which is notorious for snubbing the 20th century, had a narrow interest in Northern European modernism with superb works by Edvard Munch and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. Before joining the MFA as its director, Perry Townsend Rathbone, had been the director of the Saint Louis Art Museum where he was a friend of Max Beckmann. Rathbone later donated to the MFA a portrait of him by Beckmann. Under Rathbone’s watch there were major exhibitions of Beckmann and Kirchner. Oskar Kokoschka taught briefly at the Museum School and George Grosz, after the war, lived for a time on Cape Cod.

Of course this taste for the humanistic and Germanic was a strong influence on the major movement of Boston Expressionism, in the 1930s and 1940s, and its aftershocks are still richly evident among Boston painters.

As a native Bostonian, arguably, my gravitation in the arts has always been more Germanic than French. That means ascribing to the notion that the glass is half empty. There is a natural inclination to be moved by tragedy more than the comic and joyful. Encountering works of art that move one to tears tends to linger deep in our hearts and minds while the pleasant, joyful and uplifting prove to be ephemeral, and perhaps not to be trusted. Pain feels more real, profound and lasting than moments of pleasure and bliss.

Perhaps this is why there is a popular aversion to Germanic/ expressionist art. This summer, for example, one of the most successful and beloved exhibitions paired Picasso and Degas at the Clark Art Institute. Although there were some dirty pictures the galleries were mobbed with adoring, fixated visitors.

Yet again the Clark served up a crowd pleasing feast of French painting. It was hardly a rare opportunity although it had an allegedly scholarly point. That Picasso was profoundly influenced by Degas. Hogwash. The fact that the curators stretched to try to prove a flimsy thesis took nothing away for the seductive pleasure of the work.

On every level the Otto Dix exhibition, which originated in New York at the Neue Galerie, and traveled to Montreal and its Museum of Fine Arts, has rightly been noted on the Best of 2010 lists of major critics. With Chaos and Classicism, at the Guggenheim, these were the most profound, disturbing and insightful exhibitions which I viewed in 2010.

Too often there is despair and ennui when experiencing contemporary art. The leading artists are inflated by ambition, power and adulation to a scale that the work is out of proportion. Petah Coyne, for example, is an artist whom I have followed with interest for some time. Dating back to when she showed her dripped wax sculptures with Donahue/ Sosinski Gallery in New York.

This summer, her installation at Mass MoCA just seemed so arch, commercial, absurd and cold. I found it impossible to connect to with the intimacy I had experienced some years ago. In the transition to this major installation, and its really stupid trees with stuffed peacocks, it had lost all connection to its primal instincts.

The other MoCA travesty was an exhibition of celebrity/ vanity photographs by Leonard Nimoy. Take away the name and reputation of Mr. Spock and there was little or no reason to see this work in a museum context.

There seems to be a malaise in which too few of the exhibitions which I see inspire me to write about them. Thinking and writing about the work is too daunting and frustrating. Too negative. Or so challenging and disturbing that I never seem to be able to carve out the time and energy to attack the critical issues.

Encountering the Dix exhibition at the Neue Gallerie pierced me through and through like the arrows of Saint Sebastian. The work was horrific. Where I had seen a single work here and there, indeed less is more, the critical mass assaulted and bludgeoned the senses. You left the exhibition reeling and shocked. Staggered back onto Fifth Avenue having lost forever at least a fragment of sanity. It was like that final moment of Apocalypse Now when the monster Brando/Kurtz in the cave utters “The Horror, The Horror.” It is the kind of art experience from which you never recover or forget.

I bought the catalogue and determined to read it before writing a review. It is still not finished and here I am now writing about Dix in fits and frenzied starts. On this first day of the New Year, with reflection on 2010, it’s the last chance to get this done.

The Dix exhibition at the Neue Galerie was a mess. The critics have been largely unanimous in noting this. There has been praise that the Neue Galerie, which is devoted to Germanic art and design, organized the First retrospective of the work of Dix in the United States. But also regret that it was not a project for a major museum. As a historic home on Fifth Avenue the Neue Galerie has never made the transition from a mansion to a museum.

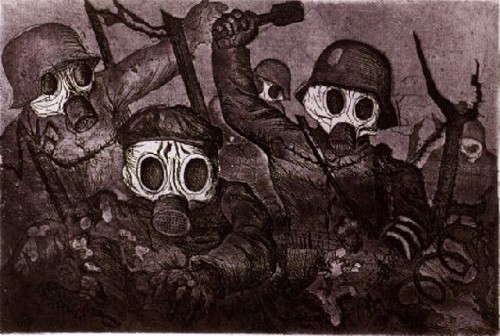

The installation was a hodge podge. The important suite of prints “Der Krieg,” which are most often compared to “The Disasters of War” by Goya, were crammed together in horizontal rows, in a dimly lit corridor. It was very difficult to really see and absorb the images which were inspired by the artist’s service during WWI in a machine gun unit of the German army. Every horrific image in the harrowing series derived from his war experience. They are to fine arts the equivalent of the novel “All Quiet on the Western Front” by Erich Maria Remarque.

The series of Dix prints were published by Karl Nierendorf in 1924. Based on these images alone Dix deserves to be regarded on the short list of the greatest artists of the 20th century. We have seen the series better displayed at MoMA and they were a focal point of the Guggenheim exhibition Chaos and Classicism.

In a gallery ill suited for the display of pictures the installation at the Neue Gallery was a chaotic scrumble by scholar, and first time museum curator, Olaf Peter. There was no semblance of order, thematic or chronological. As a result there was no opportunity for cohesion and insight as we progressed from one picture to another. We might pause and contemplate a single work but it lacked context or relationship to the next work.

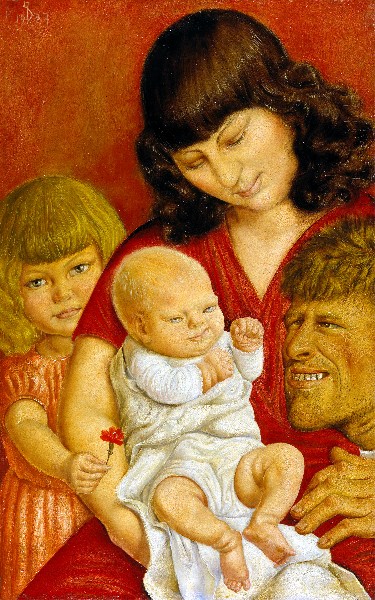

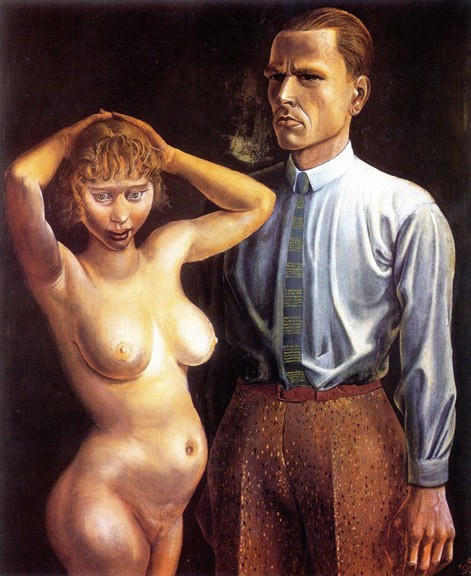

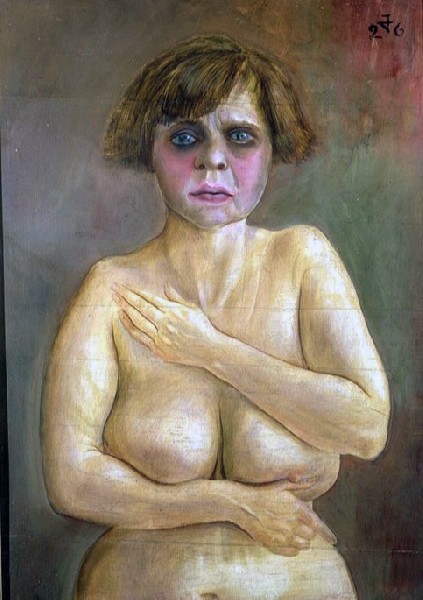

There were the smarmy nudes with sagging, flesh. None of the women are ever pretty, sensual or enticing. We saw seemingly tender family groupings. But, Dix, the father, appears to be a deranged troll. Oddly this evokes the very strange images of children in works by the German Romantic painter Philipp Otto Runge.

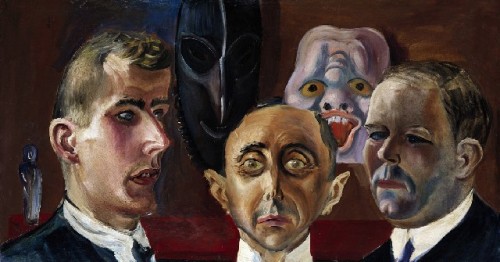

The sources and influences for Dix were paradigmatically Nordic, Germanic, Gothic and Dionysian. There are strong references to Lustmord or the horrific sexual murders and serial slayings of prostitutes that pervaded the Weimar Republic and recur in the writings, films and paintings of its artists.

While the exhibition largely proved to be a red herring, leading us into dead end metaphors, the catalogue organized by Peters is scholarly, clear, didactic and in essence the singular text in English on the work of the artist.

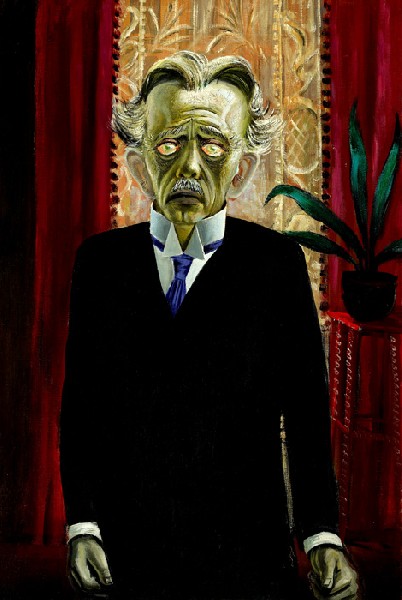

We had hoped to see the installation in Montreal. Surely its curators would do a better job of sorting through and ordering the work. Why Montreal one might ask? It seems that the museum owns a major work “Portrait of the Lawyer Hugo Simons.” In 1993 there was concern that the painting, in a private collection, would leave Montreal. Considerable sources were rallied to acquire it for the Museum of Fine Arts. Sharing the exhibition was largely in support of that effort.

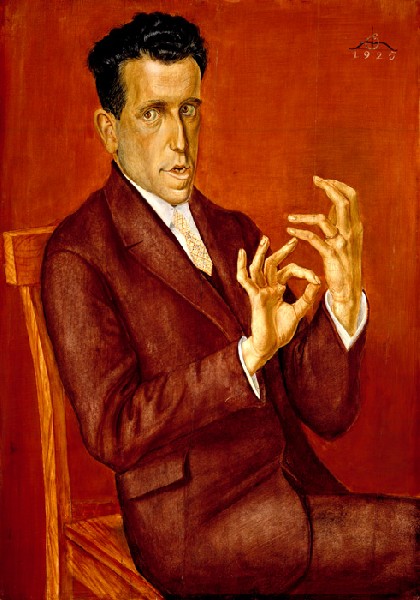

Indeed the portraits by Dix, of which Hugo Simons is among the masterpieces, are uniquely inventive and insightful. In this case we are absorbed by the elaborate gesture of the hands. Just what does it convey about the sitter who gazes out at us, mouth open, eyes sunken and self absorbed.

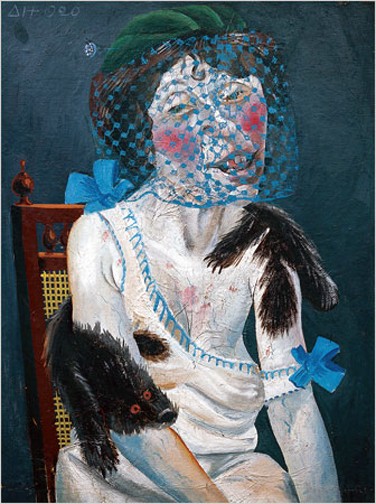

Often the portraits push the line between conveying character and devolving into caricature. I have never recovered from my first encounter with Sylvia von Harden in Paris. What to make of this very butch looking woman with a bob of hair and monocle. Looking at her open mouth you noted the yellowed teeth and their connection to the cigarettes on the café table in front of her. With a checked dress and exposed legs she conveys the paradigm of a liberated woman, an intellectual, of the era. It was a painting which I always delighted in sharing with art history classes.

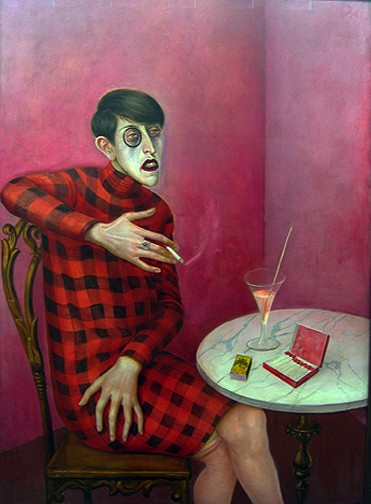

Similarly, I have always been intrigued by encountering “Portrait of the Laryngologist Dr. Mayer-Hermann” 1926 at MoMA. It is a menacing work and one would rather not have an appointment with this physician. He seems less a healer than an inflictor of pain seen with his torture inducing instruments.

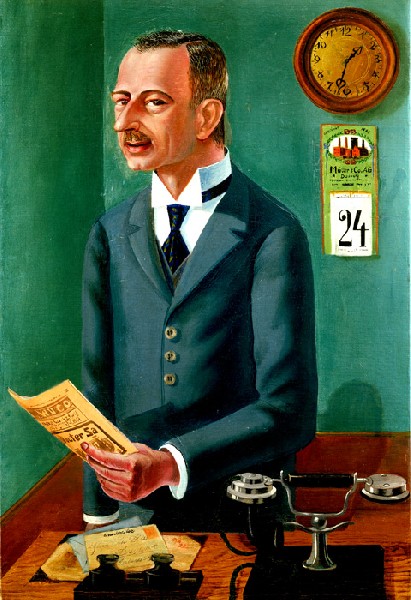

There is nothing remotely endearing and sympathetic about “The Businessman Max Roesberg, Dresden” from the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Of all the portraits it is among the most cartoonish.

The exhibition included portraits which were shocking and unforgettable. From the Art Gallery of Ontario is “The Businessman Max Roesberg, Dresden.” The eyes in particular are haunted and spooky. The face is rendered in a translucent, waxy manner that is impossible to reproduce. Another heart stopping image is “Reclining Woman on Leopard Skin” 1927. In an uncanny manner this Tiger Lady reminds one of the unfortunate New Yorker, Jocelyn Wildenstein, famously rendered grotesque, as a result of too many surgeries.

Even though Dix survived four years of service during WWI the artist was denounced by the Nazis and included in the exhibition of Entartete Kunst (Degenerate Art). Like all German artists he was forced to join the Reich Chamber of Fine Art a subdivision of Goebbel’s Cultural Ministry. As a founding member of the Neue Schlichkeit, and participant in Dada exhibitions and events, Dix was fired from his position at the Dresden Academy. He moved to a village near Lake Constance in the south west of Germany. There he remained under the Nazi radar screen creating benign landscapes and classically inspired religious paintings like “Saint Christopher IV” 1939 in the manner of Altdorfer.

In 1939, he was falsely accused of being involved in a plot to kill Hitler. He was later released. As a veteran Dix was conscripted into the Volkstrum. He was captured and then released by the French at the end of the war in 1946.

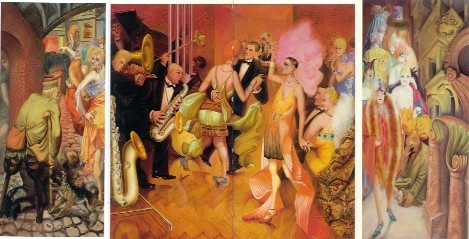

As a Degenerate Artist some 250 works by Dix were confiscated from collections and destroyed. In that sense we will never know Dix in the depth the work deserves. The exhibition included the important triptych “Der Krieg” 1932 but not the major triptych “Metropolis” from Stuttgart. These ambitious, more complex works present Dix in a context different from his portraits, works on paper and prints.

There are so many losses and omissions that this first American retrospective has provided a tantalizing but uneven understanding of the artist. Critics have noted the lack of his unique works on paper, particularly charcoal drawings and water colors.

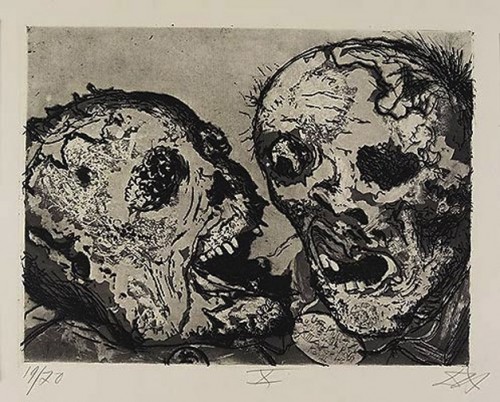

Because the work is so rarely seen in depth there remain critical and scholarly issues. Just where does Dix belong within the context of German artists of his era? With his strongly graphic and illustrative style the work of Dix seems closest to that of his friend and colleague George Grosz. As a painter/ artist the work is less experimental and compelling than Kirchner, Nolde, Heckel and Beckmann. The style of Dix was more rooted in tradition and conservative techniques of rendering. In that sense he was almost reactionary.

But in the power of ferocious and harrowing imagery surely Dix was second to none. He lived through hell, four years of carnage in which he was a participant. He stared death and the devil in the face. Dipped his pen and brush into the rank, festering pus of rotting corpses and with that demonic medium created some of the most gut wrenching images of his generation. It is an enduring triumph and legacy of how humanity prevails through what Kurtz uttered as “The Horror.”