An Outstanding Meistersinger at the Metropolitan Opera

James Levine and consistently fine cast in Richard Wagner's comic masterpiece

By: Michael Miller - Mar 19, 2007

The Metropolitan Opera, New York, March 10, 2007, 12 pm.Richard Wagner, Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg

Conductor: James Levine

Eva: Hei-Kyung Hong

Magdalene: Maria Zifchak

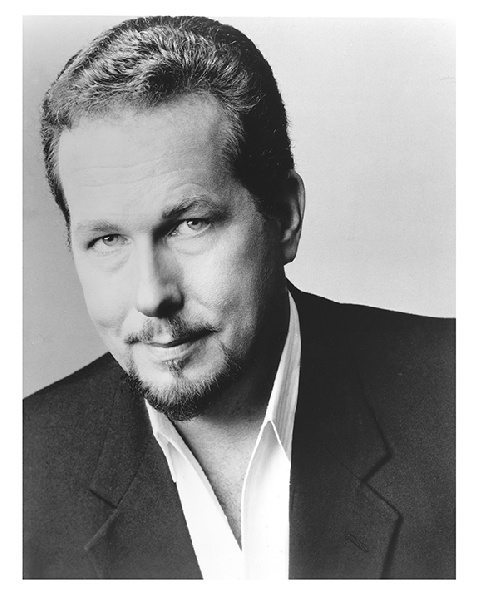

Walther von Stolzing: Johan Botha

David: Matthew Polenzani

Hans Sachs: James Morris

Beckmesser: Hans-Joachim Ketelsen

Pogner: Evgeny Nikitin

Nightwatchman: John Relyea

Production: Otto Schenk

Set Designer: Günther Schneider-Siemssen

Costume Designer: Rolf Langenfass

Lighting Designer: Gil Wechsler

Choreographer: Carmen De Lavallade

Stage Director: Peter McClintock

If Journey's End is a most welcome revival of a neglected treasure of the 1920's, Saturday's matinée performance of Wagner's comic music drama, Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, marks an even more welcome return to one of the world's great homes of opera after four years on the shelf. In this context it is worth noting that every one of Wagner's works, beginning with Der Fliegende Holländer, has held a solid place in the repertory of major opera companies to the present day. One can't say that even of Mozart and Verdi. Expense is usually the only limitation, apart from the shortage of singers able to manage the physically and artistically difficult principle roles. The Met usually schedules only one or two productions a year, and they almost always sell out. If this complex music drama has been misunderstood in the past, misused, or abused, it is a subject for historians rather than the opera-lovers of today, but it is perhaps still easier to approach it straighforwardly, as a masterpiece to be enjoyed immediately in the theater, in New York than in Germany, where it still raises uncomfortable questions of national identity. There is no denying its patriotic thrust, and that sentiment, I find, is a questionable one, as dangerous in the United States as in Germany. At least in the Meistersinger it is interesting, since it was first performed just on the eve of Bismarck's creation of a unified German state.

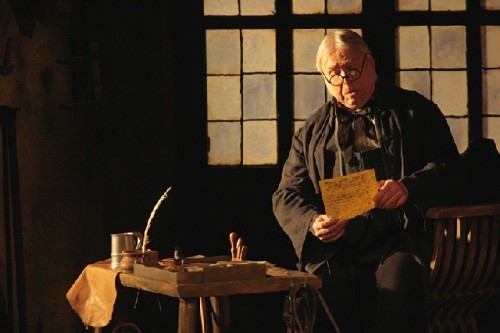

The current Metropolitan production by Otto Schenk with sets designed by Günther Schneider-Siemssen, which originated in 1993, is basically a traditional one, largely faithful to Wagner's detailed indications, and shows absolutely no signs of aging. In fact I believe I noticed some refinements in the staging over past performances, although I can't prove it with specific examples. Perhaps it was my response to the extraordinarily consistent and dramatically gifted singers in this year's cast, not to mention Levine's lively appreciation of its theatrical values. At the very least the audience will be elated by an imaginary journey into a picturesque community of a bygone time, when society seemed somehow more vigorous, however prone to argument or open conflict its citizens may have been. Wagner tempered his romantic imagination with his sharp intelligence, and his characters are many-sided, real, and rarely on their best behavior. The better one knows the nooks and byways of the score and the constant repartee in the libretto, the better one can appreciate its humour and wit, a sarcastic wit which is occasionally not only wicked, but a little nasty. No one is innocent. Innocence is dead in this world, as the recurring motif of Adam and Eve reminds us. For Wagner art could effect its true power only in a world in need of redemption. What's more, Wagner, following Aristophanes' example, saw a lesson in his comedy, both for the present (1868) and the future, as he conceived it, and at the very end he gives Sachs a moving parabasis on the subject.

In Boston and the Berkshires there has been much discussion of the relaxation in Levine's conducting, and this is equally apparent in this year's Meistersinger. As in the Tanglewood Don Giovanni this past summer, he showed the utmost sensitivity to his singers' need for flexible tempi and dynamics, and, as perfectly focussed as the ensemble was throughout, I found myself paying less attention to Levine's specific decisions about tempo and balance—except in his characteristic broad tempi in passages like the prelude to the third act and Sachs's Wahn monologue—than to the way in which all elements of the production came together. Levine's flow seemed more natural than ever, never compromising the score, while leaving us free to become engrossed in the dramatic action and the characters. I've never been more inclined to focus on the stage, rewarded by the remarkably well-rehearsed and spirited acting of the singers. In this respect Matthew Polenzani as David (whom locals will remember for his superb Don Ottavio in Don Giovanni at Tanglewood last summer) and the Beckmesser, Hans-Joachim Ketelsen, were particularly outstanding, and neither ever failed to exploit their remarkable vocal gifts. It's been a long time since Wagner audiences would accept a caricatural Beckmesser, with the all-too-familiar distortion of the voice into a nasal whine, and Ketelsen's portrayal was complex, three-dimensional, and convincing, taking full advantage of the rich voice which served him so well in his very moving Kurwenal in the Met's 1999 Tristan und Isolde. Matthew Polenzani, I believe, is pretty much the finest David I have heard on the stage. His focussed tenor voice with its attractive dark color and his good looks gave him a commanding presence, and he had clearly studied the part in every aspect, producing a richly varied and well-rounded portrayal of a character who is often taken for granted. He really carried a good part of the first act, when David explains the craft of the Meistersinger to an impatient Walther, on his own. The Russian bass Evgeny Nikitin did full justice to Eva's father, Veit Pogner, with his attractive voice and expansive phrasing. Such consistent strength in these supporting roles is not as common as it should be, and it is crucial in Die Meistersinger, which is above all an ensemble opera, demanding the best from everyone, from the Lehrbuben to Sachs himself.

Hei-Kyung Hong's Eva was attractive and mischievous. She was fully into her part and sang splendidly. Her rich, brilliant soprano was perfect for the character. Johan Botha also acted with intelligence and enthusiasm. His large but flexible voice is capable of a great range of color. It did not open fully until about the middle of the first act, constraining slightly his fist amorous exchanges with Eva, but once it did, it was truly magnificent. The intelligence and good taste of his phrasing were impressive throughout. This made his "Fanget an" in the first act particularly interesting, and all three appearances of the Preislied were absolutely on the highest vocal and interpretive level. Even in the third repetition he showed no signs of fatigue or strain. Botha truly a great Walther. James Morris's Sachs has been justly respected for the burnished texture of his voice and his considered interpretation. He is strong and bold when he needs to be, as in the second act, and introspective in Sachs's great monologues in the third. He has no trouble projecting this thoughtfulness even when addressing the crowds on the Festwiese. His Sachs is not only a grave philosopher and a respected Meistersinger, but he has a sense of humor as well as his own emotional engagement in Walther and Eva's predicament. He brings across Sachs's conflicted emotions in Act III, scene 1 in a thoroughly persuasive and unaffected manner. His range and nuance remind us that he studied Sachs and Wotan with Hans Hotter, whose understanding of these roles remains unsurpassed.

This was certainly one of the great Meistersingers I've had the good fortune to attend. The Met's intelligent and beautiful production, Levine's coherent and sensitive understanding of the score, as well as the outstanding level of not only the lead singers but the entire ensemble did full justice to Wagner's vision. It was also a special event for me, because my sixteen-year-old son, Lucas, was with me, attending his first Wagnerian performance. He was as delighted as I was. Nothing was lost on him. Between the stage action, the music, and the Met titles, he said, the six hours went by quickly, and he was in the mood to stay on for the evening performance, which, unfortunately we could not do. The Metropolitan Opera has earned itself another Wagnerian regular, and I can envision him coming back for many years to come. We are already making plans for the Kirov Ring des Nibelungen at the Met this July and Don Carlo at Tanglewood. There may be a few houses in Europe which are as strong as the Met, but I don't believe any does as much to keep the art alive. All it really needs are top-quality productions that are true to the works, and the Met excels at that.