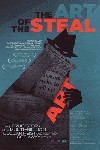

The Art of the Steal At the Coolidge

Heist of Barnes Foundation Art Documentary

By: Mark Favermann - Mar 28, 2010

The Art of the Steal (2009)A Documentary about the struggle and eventual heist of the $25 billion Barnes Foundation Art Collection

Directed by Don Argott

Cinematography by Don Argott

Now playing at the Coolidge Corner Theatre, Brookline, MA

www.coolidge.org

The Art of the Steal is a stunning documentary film about the turbulent history of the Barnes Foundation. It will be of interest to anyone concerned with art, cultural history, social class, government machinations and issues of race, wealth, power and culture. Director Don Argott has created a wonderfully colorful and thoughtful story laced with good guys, bad guys and great art.

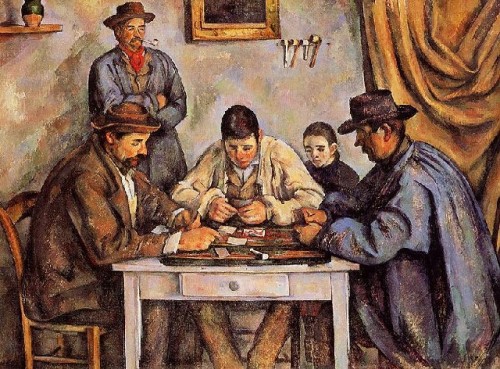

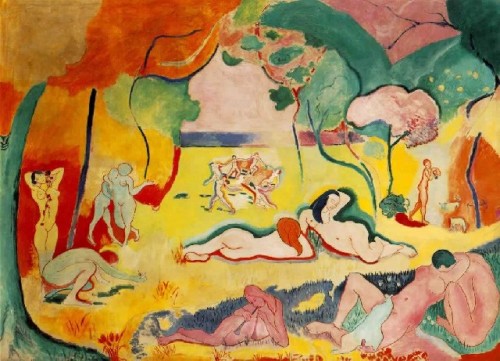

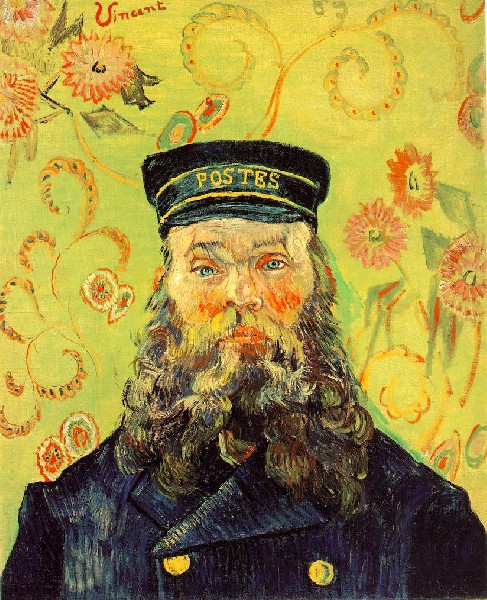

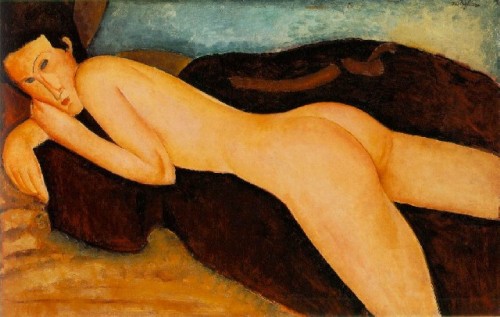

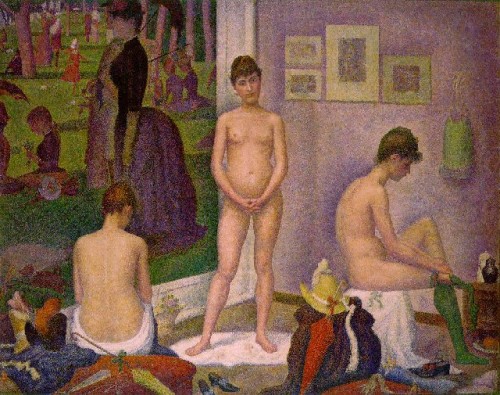

The Barnes Foundation in Merion, Pennsylvania (a tony suburb of Philadelphia) has always been spoken about in art circles as a jewel of a collection, a holy of holies of the artworld, a sanctum sanctorum of great art. Arguably the best early Modern, French Impressionist and Post Impressionist compilation in the world, the collection includes huge number of masterpieces by Pierre-Auguste Renoir (181), Paul Cezanne (69), Henri Matisse (59), Pablo Picasso (46), Chaim Soutine (21), Henri Rousseau (18), Amedeo Modigliani (16), Edgar Degas (11), Vincent van Gogh (7), Georges Seurat (6), Edouard Manet (4), and Claude Monet (4).

Renowned for its late 19th and early 20th Century European paintings, the Barnes Foundation's collection also includes important examples of American paintings and works on paper, by Charles Demuth, William Glackens, and Maurice and Charles Prendergast. The collection includes African sculpture, Native American ceramics, jewelry, and textiles as well as Asian paintings, prints, and sculptures. Medieval manuscripts and sculptures, Old Master paintings, including works by El Greco, Peter Paul Rubens, and Titian, ancient Egyptian, Greek, and Roman art, and American and European decorative arts and metalwork are all plentiful as well.

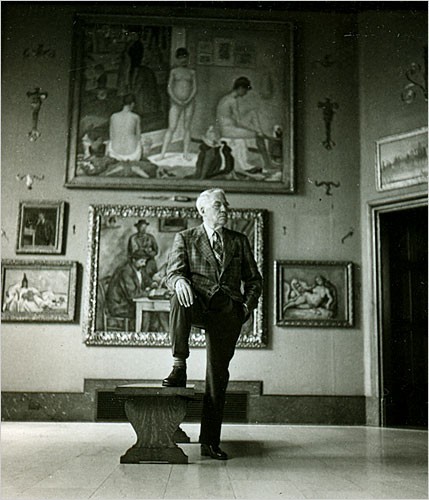

Dr. Alfred Barnes (1872-1951) was the son of a butcher in a working class neighborhood of Philadelphia who worked his way through the University of Pennsylvania majoring in chemistry before taking a degree in medicine. He made his fortune with the invention and development of the antiseptic Argyrol, a cure for Gonorrheal blindness in newborns. He was known as an eccentric, larger than life figure. He was passionate about educating the underprivileged. Astutely, he sold his company in 1929 before the Stock Market Crash and the introduction of other stronger forms of antiseptics. The money that he made was used to build his magnificent collection.

Earlier influenced by his high school friend painter William Glackens to appreciate art, his passionate love for great art was awakened in his mid-30s while visiting and living part time in Paris. With a intuitive sophisticated and wonderful eye and innate ability to judge artistic greatness, Barnes started to build his incredible and brilliant collection. Barnes also hated the power elite of the City of Philadelphia. Therefore he wanted to build an artistic oasis for serious students who could learn from his collection away from those who wanted art as a backdrop and as a tourist location. Dr. Barnes never wanted to create a museum.

The Barnes collection was built during a time when the conservative and arrogant Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art and certainly the Boston Museum of Fine Arts had little or no interest in the French Impressionists, Post-Impressionists and Early Modern works coming out of Europe. These works and artists were considered not at all by these still august institutions. Today, the works in the Barnes are estimated to be worth $25 to $30 billion. That's right, nearly priceless.

Barnes especially hated along with others of Philadelphia's elite (Main Line) establishment, the power-brokering wealthy Annenberg family (father Moses or Mo and son Walter) that owned the Philadelphia Inquirer and other major publications. Through their publication, the Annenbergs expressed how they wanted his collection to be more accessible to the public and even to reside in the Philadelphia Museum of Art which many of the elite were very involved with. When Barnes first showed part of his collection at the Pennsylvania Arts Academy, the city's Museum of Art and the local art critics had scorned the collection. Dr. Barnes never forgot this massive insult.

When in retrospect the value and depth of Dr. Barnes' collection became clearer, the Philadelphia elite felt that this was too much grand art to be residing in a more or less isolated small township suburb. This was a detail like all others of his collection that Barnes personally and carefully crafted. Other details included grouping art, furniture and decorative elements together as well as the various groupings of art by particular artists individually and with others to create visual conversations among the pieces and artists.

To protect his vision, Dr, Barnes hired some top Philadelphia lawyers to draft an iron-clad will that not only endowed his foundation with appropriate funds to maintain the collection where and how he saw it in perpetuity. Purposely, he had included in the will the codicil that the collection could not go anywhere near the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Through political twists turns and power elite deals, nearly 60 years after Dr. Barnes' accidental death in a car wreck, the opposite of what Barnes had wanted is now going to happen.

The Barnes Foundation collection is being moved to Philadelphia with oversight from the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Through well placed interviews and historical linkings, Don Argott documents this literal hijacking of the Barnes collection as the greatest art thefts of the century. This was a daylight robbery by brazen thieves. The culprits included elected officials, members of the Philadelphia establishment and even Barnes Foundation Trustees. Over the years, they were aided and abetted by slanted reporting and editorials by the Annenberg 's Philadelphia Inquirer. All of their actions were justified by the need to place the needs of the greater public over the desires of the dead millionaire.

Like all good stories, this film has good guys and villains. There were many villains in the story. Strangely, a few involve Lincoln University, a small traditional Black college founded in 1858 to educate middle class Black students. To piss off the Philadelphia elite, Barnes gave control over his foundation to Lincoln University. However for the next 30 years, the Barnes Foundation was run by one of Barnes' former assistants, Violette de Mazia, who kept things as Dr. Barnes would have wanted them to be. When de Mazia died, a villain of sorts appeared in the 1990s, the chairman of Lincoln University's Board, a slick attorney and politician Richard H. Glanton.

The articulate Glanton used problems caused by the Barnes' deferred maintenance and local zoning to force expensive and frivolous lawsuits on the township to break Alfred Barnes' will's intent. Additionally, a profitable world tour of the collection, which brought him personal honor and prestige, ended in financial instability for the institution. However, even though Glanton depleted the Barnes Foundation endowment, he was not the worst of the villains. Another Lincoln University appointee, Dr. Bernard Watson, the current Barnes chairman, has literally sold the foundation down the river to Philadelphia. The former mayor of Philadelphia and current Governor of Pennsylvania, Ed Rendell, is shown to be one as well. He along with state senators, city and state officials as well as a supposedly "fair' district court judge, the Honorable Stanley Ott, are all culpable.

There were others who were made to appear evil or having a disturbingly dark agenda in the film as well. These included the usually benign and culturally generous Pew Foundation, the Lendfest Foundation and the Annenberg Foundation. Yes, the same Annenberg family's charitable trust. The villains were presented in the film as just waiting to grasp the Barnes Foundation and carry it off kicking and screaming to Philadelphia placing it at Dr. Barnes' nemesis, the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

To be fair, the film paints the "bad guys" very broadly and does not allow for much of a response to the notion allowing the public to experience this great collection rather than it be limited to a few scholars and a select group of students. What is really wrong with this? Here the social good has prevailed over private desires. However, the difficult point is that what has occurred is counter to the explicit desires of Dr. Alfred C. Barnes. He was very specific about this. His wishes as stated in his last will and testament are now not being followed. The Art of the Steal demonstrates that $25 billion in art and aggressive politicians and establishment types can eventually trump an eccentric millionaire's thoughtful and legally stated last desires. This story and film is provocative on many levels.

In 2012, a new Barnes Foundation will open in Philadelphia. The art collection will then be shared by all as a fabulous new public museum. Dr. Alfred C. Barnes is spinning in his grave.