Edifice Wrecks: What's With New York City?

Urban Visions are Being Ruined by Parochial Hubris

By: Mark Favermann - Mar 29, 2008

Since I was a child in the 50's, a visit to New Your City always got my heart pumping. Environmentally invigorating and just plain exciting, New York, New York felt different from any other place. And, it was. The wall of skyscrapers, the varying neighborhoods, the street grid, the variety of shops and stores, the noise both visual and aural and the wonderful mix of people added to the cacophony of ethnicity, urban grit, elegance and scale. My steps as well as those countless others' were always a little quicker when in New York. Here, energy flowed from the city to the visitor. New York still has great energy, but there seems to be something vitally missing in "The City" in the past few years.Of course, the confidence, the bravado, the great and often deserved swagger of American corporations and capital markets were devastated by the tragedy of 9/11. This was so unexpected and so unfair. But instead of grieving properly and getting appropriate distance and therefore perspective, almost immediately major local and international architects, grieving relatives as well as civic and political leaders started pushing for a major design statement to reflect the tragic results of the loss at the Twin Towers. Has there been just too much too early or too little real thought and too little civic and private commitment to get things done? The resulting mess of the 9/11 international site competition and the related memorial morass has led to creative dumbing down and urban stasis.

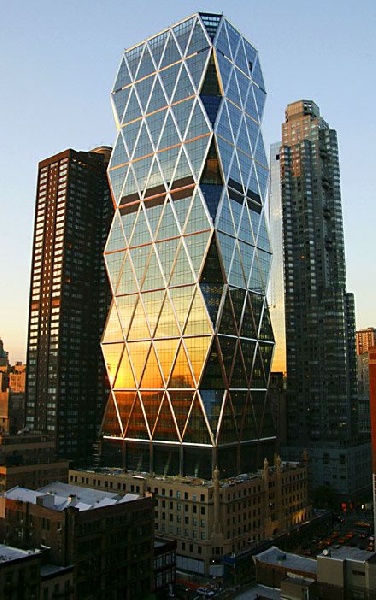

Certainly, there continues to be a number of creative examples of prominent buildings by innovative architects in New York City. However, these are finite, complete entities in themselves. They may be an architectural vision in an urban setting. But, individually these are not urban design schemes. Some recent notable examples include the artful pile of boxes that forms the New Museum of Contemporary Art by the Japanese firm Sanaa, on the Bowery at Prince Street on the Lower East Side, Frank Gehry's iridescent IAC Headquarters Building along the West Side Highway in Chelsea that he created for Barry Diller and Lord Norman Foster's Hearst Magazine Building in Midtown Manhattan at 47th Street and 8th Avenue. Several others have been built or are in process as well.

In recent years, New York City has certainly had an awful, no terrible, track record with many of its supposedly next great civic projects. Just look at such mega-failures as Battery Park City, the upscale housing project located on the riverfront, The MetroTech Center, a California-like big tower backroom cluster city and Donald Trump's on-again/off-again once grand Riverside South. All are splotches on the urban environment.

Each one of these projects is a bland strangely uniform rip in the urban fabric. They are certainly just as boring and uninspired as the worst of the Modernist super blocks they were suppose to thoughtfully and sensitively improve on. Add to the list, the excruciatingly bogged-down Ground Zero project, the rather embarrassingly failed 2012 Olympic Bid and the eagerly anticipated but now recently postponed Atlantic Yards project in Brooklyn. What does the song say? "If you can make it there, you can make it anywhere." But, lately great even just good urban thinking and vision just can't make it there. That clearly leaves the proposed projects absolutely nowhere.

New York State officials, prominently led by former Governor George Pataki, various pertinent and several rather impertinent state agencies, the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation (LMDC) and the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey along with designated developer Larry Silverstein and his corporate architecture lapdog architect, Skidmore, Owens and Merrill (SOM) added little to the cooking up of the often stranger than fiction Ground Zero Project bouillabaisse. This tragically messy soupcon of bureaucracy and procrastination never aided design quality or urban vision in terms of forwarding the project. Sprinkle in angry community stakeholders (the residents and businesses who are most affected by the project's aspects), dissident architects and urban designers and New York's untidy design review process and you get what happened—plans not only gone awry but in some cases like the winning design schemes literally gone asunder. After almost seven years, work has finally started on the almost completely modified Freedom Tower and its structural siblings, World Trade Center Towers 3 and 4.

Like a ghost, Daniel Libeskind's 2002 competition-winning site plan has virtually vanished being superseded by SOM's developer-driven Freedom Tower interpretation and its adjacent buildings. Couple this strategic architectural conflict of the mediocre over the potentially poetic with the disastrous result of the competition-winning Michael Arad memorial and memorial plaza. The process had no distance, little real perspective. Nerves were just too raw. First, Arad was driven to merge his design with landscape enhancement eminent landscape architect Peter Walker. This has led to another war of wills and egos in regard to the final interpretation of the site. The young untested designer versus the old master landscape architect.

Secondly, the memorial museum has been placed on the site and has evolved. At times, it seems that Arad's memorial staggers on the edge of collapse. The names of the Twin Tower victim's have been moved from below grade to above. This is due to the cost reduction of the removal of the previously incorporated ramps. Thirdly, the last cost estimates are supposedly around one billion dollars. According to Peter Walker, the actual number is closer to $500,000. Still, big bucks. Walker also says that this project has been his hardest project ever.

Mayor Bloomberg's folks have demanded the original simply elegant but now greatly enhanced design to be scaled back. Designer Arad has had to fight the LMDC all along the way as well. It should be noted that not just in New York, but throughout the United States, community development corporations (CDCs) have become another form of bureaucratic overlay and operate rather independently but use resources that may be better applied to less institutionally-centered community-based entities. That is a nice way of saying that a CDC may not be an urban entity's friend.

Since he first won the memorial competition, Michael Arad has had to defend his design from attacks by the deeply entrenched cronyism and slip-shod management of this powerful community development corporation. To say that Arad's relationships with the various other architects and landscape architects have been rancorous would be an understatement as well. Both sides seem to be involved in personal attacks on each other. There is great pressure on the LMDC to complete the project by 2009 to give former Governor Pataki a personal legacy. Arad does not want to be pushed into anything.

Arad has been accused of tantrums and threats. Added to this is the fact that many members of the various victims groups do not like his design. There are several victims' relatives groups, and they have been empowered from early on in this process. This is an awkward situation: a national even international memorial that has given individual mourners some veto power. Against Arad, claims of him causing great delays and being uncooperative have been the main complaints by the other players. And, so it goes.

Though initially short-listed, the NYC 2012 Olympic Bid was an almost totally city-orchestrated affair that came up embarrassingly short against other major world cities. Mayor Michael Bloomberg's erstwhile deputy mayor, Daniel Doctoroff initially ran the bid process. Previously, Doctoroff was the managing director of a highly successful private equity firm. He left the bid committee to become Bloomberg's deputy mayor for economic development and still exerted great influence in the NYC 2012 Bid process.

When 9/11 occurred, there seemed to be a strange sense of entitlement connected to the NYC Olympic bid. Sympathy maybe, but outright self-entitlement rarely works for the representative of the richest nation in the world. Few if any individuals were brought in to assist the bid group who had actually worked on a bid before or had much Olympic experience. Those that did seemed to be old school and had experience with more tame cities like Atlanta or were old uncreative suits from bygone years of the once more influential US Olympic Committee. Out of touch means out of the Games.

Moral: sometimes you may think that you are smarter than you actually are and don't find out until it is too late.

London won the 2012 bid while NYC was eliminated in the second round of voting. Part of the New York bid weakness was that the City did not seem to speak with one voice. Various interest groups(what a surprise for NYC) including major corporations complained about and fought against venues such as the proposed West Side Stadium. Mayor Bloomberg saw the West Side stadium as a catalyst to develop the far West Side of the city. Others saw it as a commercial threat. An obscure State of New York board denied a $300 million appropriation. So, it looked to the International Olympic Committee that New Yorkers could not agree. Also, financing was iffy and that coupled with 9/11 entitlement caused the Lords of the Rings to deny New York the 2012 Olympic Games. Certainly, the bid could have been much more graceful, and certainly the Bid Committee should have reached out for better and not as much New York-centric advice. Bloomberg lost again. Remember, you can always tell a New Yorker, but you can't tell him much.

Historically, NYC gave the world Rockefeller Center, the 22 acre midtown development that became the elegant symbol of 20th Century urban glory. For the past decade, it was thought that the Atlantic Yards Project in downtown Brooklyn had the same possibility as a 21st Century brilliant metropolitan core. It is a mixed-use commercial and residential development project composed of 16 buildings, currently proposed in the neighborhoods, adjacent to Downtown Brooklyn.

The centerpiece of the development is to be the Barclays Center, which would serve as the new home of the New Jersey Nets Basketball Team. Over a third of the project would be built over a train yards of the Long Island Rail Road. The Atlantic Yards project is being developed and overseen by Forest City Ratner and designed by eminent architect Frank Gehry. This would clearly be Gehry's largest physical and thus aesthetic impact on New York City.

The project has been often considered the most controversial in New York in quite awhile. While fierce opposition to the environmental effects has led to several legal battles, the ultimate threat to its completion is the credit crisis along with the weakening housing market. In March 2008, shrewed, wealthy, highly politically connected principal developer Bruce Ratner acknowledged that the slowing economy may delay construction of both the office and residential components of the project for several years. Mayor Bloomberg has been an early and strong supporter of this project. Clearly, a brilliant financial genius like Bloomberg has met his match in New York development challenges. Mayor Michael Bloomberg's NYC development legacy will be sparse indeed.

As I see it, the problem is, among other things, a true lack of civic leadership beyond the politically elected and appointed individuals. This is a problem in older cities like Boston as well where multinationals have taken over from locally based or strongly historically connected corporations and institutions. In NYC, individual building projects are still being done with regularity and even creative prominence. However, urban design schemes cannot seem to get past banal parochialism, cronyism, nimbyism and turfism. And now there is a major real estate credit crunch as well.

Looking back forty or fifty years ago, the incredibly powerful New York State Parks and Transportation Commissioner Robert Moses could actually move whole sections of the city to build roads and parklands by bureaucratic mandate. One of his greatest opponents was urban residential rights advocate Jane Jacobs who espoused the concept of the urban village. Dubai and Beijing seem to take the Moses development approach dictating massive developments of spectacular architectural and urban development projects. Dictatorships make project completion easier. However, Beijing is eroding its historic housing culture with unknown consequences while building mega-icons. Dubai is basically a new town without any historical precedence creating some of the largest structures in the world. It is a strange oil-driven colossus on the edge of the desert. Will it be a true city-state or a business-pleasure oasis?

For New York City, the answer can be found in a need for a serious reworking of earlier models that allow development project proposals to be more clearly stated to stakeholders. There must be a clear set of rules for projects that intrinsically underscore the common good. We must remember that this is what Robert Moses did. This is how each of his projects was justified: by stating that they were each primarily for the common good. This did occur even if he was rather dictatorial and ham-fisted in his approach. This does not seem to be very clear in today's NYC environment. It seems that development projects are primarily for economic advancement. And this is not necessarily for any higher purpose in the city but for the benefit of developers.

Mayor Bloomberg's folks have demanded the original simply elegant but now greatly enhanced design to be scaled back. Designer Arad has had to fight the LMDC all along the way as well. It should be noted that not just in New York, but throughout the United States, community development corporations (CDCs) have become another form of bureaucratic overlay and operate rather independently but use resources that may be better applied to less institutionally-centered community-based entities. That is a nice way of saying that a CDC may not be an urban entity's friend.

Since he first won the memorial competition, Michael Arad has had to defend his design from attacks by the deeply entrenched cronyism and slip-shod management of this powerful community development corporation. To say that Arad's relationships with the various other architects and landscape architects have been rancorous would be an understatement as well. Both sides seem to be involved in personal attacks on each other. There is great pressure on the LMDC to complete the project by 2009 to give former Governor Pataki a personal legacy. Arad does not want to be pushed into anything.

Arad has been accused of tantrums and threats. Added to this is the fact that many members of the various victims groups do not like his design. There are several victims' relatives groups, and they have been empowered from early on in this process. This is an awkward situation: a national even international memorial that has given individual mourners some veto power. Against Arad, claims of him causing great delays and being uncooperative have been the main complaints by the other players. And, so it goes.

Though initially short-listed, the NYC 2012 Olympic Bid was an almost totally city-orchestrated affair that came up embarrassingly short against other major world cities. Mayor Michael Bloomberg's erstwhile deputy mayor, Daniel Doctoroff initially ran the bid process. Previously, Doctoroff was the managing director of a highly successful private equity firm. He left the bid committee to become Bloomberg's deputy mayor for economic development and still exerted great influence in the NYC 2012 Bid process.

When 9/11 occurred, there seemed to be a strange sense of entitlement connected to the NYC Olympic bid. Sympathy maybe, but outright self-entitlement rarely works for the representative of the richest nation in the world. Few if any individuals were brought in to assist the bid group who had actually worked on a bid before or had much Olympic experience. Those that did seemed to be old school and had experience with more tame cities like Atlanta or were old uncreative suits from bygone years of the once more influential US Olympic Committee. Out of touch means out of the Games.

Moral: sometimes you may think that you are smarter than you actually are and don't find out until it is too late.

London won the 2012 bid while NYC was eliminated in the second round of voting. Part of the New York bid weakness was that the City did not seem to speak with one voice. Various interest groups(what a surprise for NYC) including major corporations complained about and fought against venues such as the proposed West Side Stadium. Mayor Bloomberg saw the West Side stadium as a catalyst to develop the far West Side of the city. Others saw it as a commercial threat. An obscure State of New York board denied a $300 million appropriation. So, it looked to the International Olympic Committee that New Yorkers could not agree. Also, financing was iffy and that coupled with 9/11 entitlement caused the Lords of the Rings to deny New York the 2012 Olympic Games. Certainly, the bid could have been much more graceful, and certainly the Bid Committee should have reached out for better and not as much New York-centric advice. Bloomberg lost again. Remember, you can always tell a New Yorker, but you can't tell him much.

Historically, NYC gave the world Rockefeller Center, the 22 acre midtown development that became the elegant symbol of 20th Century urban glory. For the past decade, it was thought that the Atlantic Yards Project in downtown Brooklyn had the same possibility as a 21st Century brilliant metropolitan core. It is a mixed-use commercial and residential development project composed of 16 buildings, currently proposed in the neighborhoods, adjacent to Downtown Brooklyn.

The centerpiece of the development is to be the Barclays Center, which would serve as the new home of the New Jersey Nets Basketball Team. Over a third of the project would be built over a train yards of the Long Island Rail Road. The Atlantic Yards project is being developed and overseen by Forest City Ratner and designed by eminent architect Frank Gehry. This would clearly be Gehry's largest physical and thus aesthetic impact on New York City.

The project has been often considered the most controversial in New York in quite awhile. While fierce opposition to the environmental effects has led to several legal battles, the ultimate threat to its completion is the credit crisis along with the weakening housing market. In March 2008, shrewed, wealthy, highly politically connected principal developer Bruce Ratner acknowledged that the slowing economy may delay construction of both the office and residential components of the project for several years. Mayor Bloomberg has been an early and strong supporter of this project. Clearly, a brilliant financial genius like Bloomberg has met his match in New York development challenges. Mayor Michael Bloomberg's NYC development legacy will be sparse indeed.

As I see it, the problem is, among other things, a true lack of civic leadership beyond the politically elected and appointed individuals. This is a problem in older cities like Boston as well where multinationals have taken over from locally based or strongly historically connected corporations and institutions. In NYC, individual building projects are still being done with regularity and even creative prominence. However, urban design schemes cannot seem to get past banal parochialism, cronyism, nimbyism and turfism. And now there is a major real estate credit crunch as well.

Looking back forty or fifty years ago, the incredibly powerful New York State Parks and Transportation Commissioner Robert Moses could actually move whole sections of the city to build roads and parklands by bureaucratic mandate. One of his greatest opponents was urban residential rights advocate Jane Jacobs who espoused the concept of the urban village. Dubai and Beijing seem to take the Moses development approach dictating massive developments of spectacular architectural and urban development projects. Dictatorships make project completion easier. However, Beijing is eroding its historic housing culture with unknown consequences while building mega-icons. Dubai is basically a new town without any historical precedence creating some of the largest structures in the world. It is a strange oil-driven colossus on the edge of the desert. Will it be a true city-state or a business-pleasure oasis?

For New York City, the answer can be found in a need for a serious reworking of earlier models that allow development project proposals to be more clearly stated to stakeholders. There must be a clear set of rules for projects that intrinsically underscore the common good. We must remember that this is what Robert Moses did. This is how each of his projects was justified: by stating that they were each primarily for the common good. This did occur even if he was rather dictatorial and ham-fisted in his approach. This does not seem to be very clear in today's NYC environment. It seems that development projects are primarily for economic advancement. And this is not necessarily for any higher purpose in the city but for the benefit of developers.

Things do change, however. Even Jane Jacobs' urban village has been appropriated by wealthy city dwellers in expensive dwellings. Contrary to Jacobs' own views, many young and older urban villagers actually wanted the bland suburbs. Recent large proposed projects have primarily been about corporate wealth and added value. Old, unsuccessful approaches do not work any longer. But, perhaps there is somewhere a middle ground?

It should all start with new, strong civic leadership. Politicians and corporate as well as institutional leaders must stand up, be counted and actually lead. Public good is the issue. The key is civic responsibility. This is certainly easier said than done. Architects and urban designers as citizens may often be too self-interested to show the way themselves. However, for their clients, these designers should employ the best tools and professional practices. For their fellow citizens, they should insist upon more bureaucratic and development transparency. In the best of all possible worlds, they can at least use their creativity and technical knowledge to assist in the fostering of the best urban design process for New York. I am not suggesting that everyone sit in a circle and sing Kum-Bye-Ya, but there has to be a better way. It just has to be found in New York and found soon.

It should all start with new, strong civic leadership. Politicians and corporate as well as institutional leaders must stand up, be counted and actually lead. Public good is the issue. The key is civic responsibility. This is certainly easier said than done. Architects and urban designers as citizens may often be too self-interested to show the way themselves. However, for their clients, these designers should employ the best tools and professional practices. For their fellow citizens, they should insist upon more bureaucratic and development transparency. In the best of all possible worlds, they can at least use their creativity and technical knowledge to assist in the fostering of the best urban design process for New York. I am not suggesting that everyone sit in a circle and sing Kum-Bye-Ya, but there has to be a better way. It just has to be found in New York and found soon.