Chile and Argentina: Part one

Santiago de Chile and Easter Island

By: Zeren Earls - Mar 30, 2013

My annual winter getaway took me to Easter Island and Patagonia in February. I felt fortunate to be able to fly out of Boston on a snowy morning, as a storm had shut down the airport a week before. Changing flights in New York, I journeyed south to Santiago de Chile – an eleven-hour trip – which put me two hours ahead of Eastern Standard Time. Following dinner service, I was able to fall asleep thanks to my travel pillow.

There is no visa requirement to enter Chile. However, before clearing passport control US citizens pay a reciprocity fee of $160, equal to that collected from Chileans on entering the US. I was glad to see a cab driver holding up my name. Embraced by the summer’s warmth, I took off several layers of clothing and switched to sandals during the ride to the hotel. Having arrived on an earlier flight, the other ten members of the pre-trip were already in the lobby ready for the city tour.

Settled by Spaniards in 1541, Santiago is a sprawling capital; more than a third of Chile’s 17 million inhabitants live in Gran (Greater) Santiago, between the high Andes and the lower coast range. The subway system, known as the subte, connects most of the city. We took the subte to the Plaza de Armas, the nucleus of the colonial city. Following a typical lunch of hot dog in a bun spread with avocado at an outdoor café, we walked several blocks southwest of the Plaza to the Palacio de la Moneda, the former colonial mint, which is now the seat of the government. It has not been the presidential residence since Salvador Allende shot himself fatally during General Pinochet’s coup in 1973 to end the three-year-old Marxist government. The current freely elected president, Sebastián Piñera, lives in his own home.

Police on Holstein horses work in two-hour shifts to guard the grounds of the Palacio. Very tall policemen in uniforms, inspired by German and Russian models, guard the building’s gates. Lawns and reflecting pools led the way to an imposing Cultural Center next door. Back at the Plaza de Armas, we visited its oldest surviving landmark (1748), the Catedral Metropolitana, admiring the neoclassical and Tuscan touches reflected on the glass façade of the adjacent high rise. North of the Plaza stood the French-style Post Office, the Correa Central (1882). The Town Hall and the Stock Exchange were other architectural treasures adding to the city’s charm. Merriment filled the air on this Sunday afternoon. Vendors hawked balloons and Mapuchi natives sang and danced, while children splashed by the fountain. On the way back to the subte, we stopped at a coffee shop famous for its “coffee with legs,” where all the waitresses wore very short outfits.

Our welcome dinner, combined with the one for my birthday, turned out to be an elegant affair in a high-rise revolving restaurant. As it moved slowly, the views of the Andes and downtown office towers stretched before us. While watching the mountains disappear into the sunset, we enjoyed empanadas, followed by hake with shrimp sauce, rice, and steamed vegetables. Dessert was birthday cake with a single candle. Berenice, our trip leader, presented me with a gift – a mate cup made of gourd, lined with silver at the mouth, and a silver straw. Mate is a common herbal drink enjoyed throughout South America.

The next morning we got up at 5 to meet the required three-hour check-in time for a 9:30 flight to Easter Island. We were able to leave a bag of our cold-weather Patagonia clothing for storage at the hotel. Despite the size of the city, Santiago has a relatively small airport; departure gates open one at a time, while passengers mill around a limited number of shops. Here I picked up my first purchase of the trip – a magnet with Chilean folkloric motif.

After we had been in the air for five and a half hours, a triangular island, shaped by three volcanoes, appeared below. Excited, I grabbed my camera and was able to shoot the island’s crater from the air. Setting our watches ahead by two hours, we landed at a small airport at the end of a very long runway, built by the US as an emergency landing path for shuttle flights, but never used for that purpose. The slow pace of luggage delivery on a single carrousel signaled the leisurely pace of this subtropical island, which is 2200 miles off the coast of Chile and 4300 miles southeast of Hawaii.

Our native guide, Helen, met us with a big smile and adorned us with wreaths made of flowers from the island. Enjoying the warm breezes, we walked to our bus for a 10-minute ride to the Hotel Iorana. At check-in we were entrusted with a remote control for the TV and an adapter for electrical outlets in a zippered bag along with the room key. My room had a small terrace in the back with an ocean view and palm trees. Chickens roamed the yard.

The name “Easter” was given to the island by a Dutch explorer, who arrived here on Easter Sunday in 1722. Locals use the Polynesian name, Rapa Nui (Big Island). The island and surrounding islets are the summit of a large submarine range of volcanic mountains. The 4000 inhabitants, 60% of whom are Rapa Nui (local Polynesian), live in the Great Bay of the island, which was annexed to Chile in 1888 and given Special Territory status in 2007.

Our three-day visit began with a drive through the village on the way to AnaKai Tangata, a ceremonial cave with ancient wall paintings, where competitors waited for the annual nesting of the migratory manu tara (sea swallow) on the nearby islet of Motu Nui. Then, using a reed float known as a poro, they swam to the islet to find the first egg and return with it to the main island. This struggle determined who would be the Tangata Manu (bird-man), a divine ruler for the year. Cave wall images of a half-man, half-bird creature immortalize the ancient Rapa Nui bird-man cult.

At nearby Rano Kao Volcano we viewed a freshwater crater lake, 200 meters deep and 1600 meters in diameter. Avocado and fig trees grow on its fertile slopes. Driving around the crater, we had panoramic views of the Big Bay and the village in the distance; we also came upon petroglyphs of the bird-man on rock faces. Stopping at the Orongo Cultural Center, we broadened our knowledge of the ancient native peoples through attractive drawings.

Our next discovery was a set of boat-shaped stone houses – structures up to 6 meters long with very low entrances. During excavations in 1882, human remains were found inside; the houses are believed to have been used as graves for the ariki, the island’s kings and chiefs. Each house had two small holes; in the event that a hostile spirit entered one, it was thought that the spirit of the deceased could escape through the other. We met the park ranger and his two daughters, who enjoyed seeing photos of themselves on my camera.

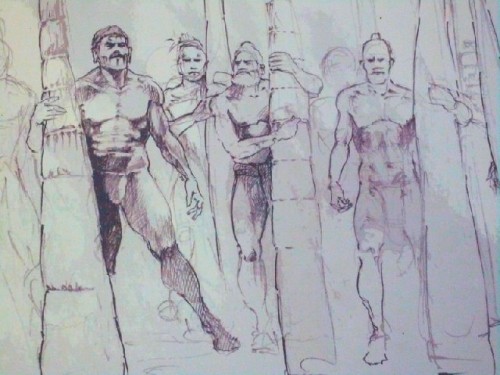

Our first glimpse of the island’s famed large stone statues, or moai, began with the toppled, broken ones in Vinapu. Representing deceased long-eared chiefs or important persons, whose bodies were interred within a coastal platform, or ahu, these statues were seen as protecting the village. Carved from volcanic tuff with stone chisels, the statues face inland, with their backs turned to the ocean. Their eyes are made of white coral and black obsidian; some have a red topknot, or pukao, representing the islanders’ long hair tied in a bun. Seeing a pile of giant stones by the water’s edge made me eager for the next day’s viewing of re-erected moai.

Early in the morning we set out on the Moai Route, visiting sacred sites. At Ahu Vaihu, sites encircled by a low stonewall, were a number of unrestored statues. In the 14th century, when short-eared commoners revolted against the royalty, all the moai, representing the king’s lineage of long-eared people, were toppled. We were able to see some of the sculptures still lying face up.

Following a box lunch of chicken, rice, vegetables, and fruit near the Rano Raraku Volcano, we visited the site of Ahu Tongariki with its 15 moai, which had been destroyed by the 2004 tsunami and restored by funds from the Japanese, who had also helped to right them by shipping over a crane. At this impressive spot I bought a small replica of a moai from a craftsman, whose flamboyantly knotted hairstyle marked his native lineage. Our walk through the landscape of moai included the largest statue, 32 feet tall though still lying on its back. At the site of Te Pito Kura (Navel of the Earth), a special spot by the ocean, there are four round stones serving as seats around a larger one; the stones are believed to give out energy when hands hover over them.

Anakena Beach, where the first Polynesian settlers are thought to have landed in 500 AD, is a beautiful bay with fine white sand. Despite the many people it attracts, amenities are minimal. I opted to change on the bus; swimming and riding the gentle waves in the salty waters of the Pacific felt wonderful. Dinner in town by the harbor, followed by a cultural show of island dances, ended our second day. On the a la carte menu I ordered grilled corvine (Chilean sea bass) with locally grown purple sweet potatoes– delicious.

The high-energy cultural show reminded me of the Maori dancers of New Zealand. Men with oiled bodies, painted faces, and grass anklets displayed bravura in percussive movements, while women in short skirts, barely covered breasts, and decorated navels excelled in lyrical hip and arm movements. A woman singer, accompanied by instrumentalists in the background, provided exuberant music. The audience was invited to join in the dance at the end.

On our final day we visited Puna Pau, the quarry that supplied the red clay for the statues’ topknots, which were shaped here and rolled downhill to their destination. A rectangular cut in a topknot keeps it steady on its head. The beautiful landscape also offers a view of nearby fields, cultivated with vegetables. The only grain grown on the island is corn; all other grains come from the Chilean mainland.

The sites of Ahu Akivi and Ana Te Pahu offered additional spectacles. The former is the only inland ahu.The seven moai here represent explorers sent by the king in around 380 AD to find new land but unable to return. Ana Te Pahu is a complex of caves, which are actually empty lava tunnels that once contained rivers of molten lava. After the lava drained out, the hollow tunnels remained. Inside one of the tunnels it was dark and damp; moving along on irregular rocks, we came to an opening in the ceiling. Framing the sky beautifully, the opening provided light for plants growing in the crevices of the cave.

In the afternoon we were free to explore on our own. I went to the craft market and visited the local church, which is a unique blend of native symbols and Catholic imagery. Walking from the village back to the hotel, I enjoyed a calafate (barberry) ice cream cone and bought a T-shirt embroidered with four moai images from the three different ahu we had visited.

An evening sunset at Tahai Beach and archeological site with rain clouds above added drama to the already spectacular setting. A brief rain shower crowded us to the edge of a nearby cave for shelter. The site contains the foundation stones of two boathouses, shaped like canoes, in addition to five re-erected moai of different sizes. As the sun went down, we enjoyed a final supper of finger food, featuring shrimp empanadas and lucana, a brandy-based local drink.

After an early morning rise and coffee, we set out for the airport to return to Santiago. Reflecting on my visit on the flight back, I felt thankful for the opportunity to see and experience this remote island’s beauty and meet its proud people. Exemplifying communal living, they all know one another and care for each other and for the land they call home, hoping to ensure the sustainability of their environment.