Namibia: Part Two

Sossusvlei and the Namib Sand Sea

By: Zeren Earls - Mar 31, 2015

Departing Windhoek on the central plateau, we traveled south in a 12-seat plane to the Sossusvlei region of the Namib Desert, which runs along the entire Atlantic coastline of Namibia. During the hour-long flight the landscape changed from towns and villages to open plains with dry river beds, to rugged mountains, then to red sand and dunes. We landed in Geluk in the middle of a rocky desert, home to Oryx and springbok. Delighted to see these animals, we rode about 30 minutes to the Kulala Desert Lodge and were welcomed by staff with refreshing washcloths and ginger-flavored cold drinks. The outside temperature was 33º C.

Our campsite was an oasis in a rough landscape. The main area with lounge, dining area, and wrap-around veranda had a sweeping view of the desert. My thatched and canvas tent on a raised wooden deck had an en-suite bathroom and a veranda with a rooftop “sky-bed” for sleeping out under the stars. The indoor bedroom had a fan and mosquito net. Pleased with the accommodations for the next three nights, I settled in quickly.

Following a brief rest, we left for a game drive and “sundowner.” On open land it was easy to spot animals — Oryx, springbok, wildebeest, jackal, and many birds. We also saw a tree bearing a very big nest built by sociable weavers. Viewing it from beneath revealed an exemplary communal dwelling constructed of many nests. Dusk turned the grazing animals into tableaus of different hues; gradually they became silhouettes with the setting sun, while we enjoyed cocktails and snacks.

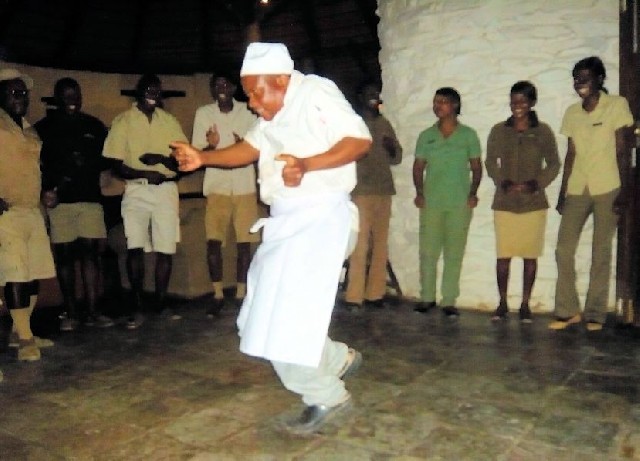

Following an eggplant appetizer, dinner was a self-serve buffet with a choice of grilled chicken, lamb or beef, butternut squash, broccoli, rice, and a salad of beet, carrot, and cabbage, accompanied by our choice of red or white South African wine. For dessert we enjoyed chocolate cake with vanilla ice cream. Our applause brought the chef out of the kitchen; in appreciation, he danced for us.

In the morning the staff woke us up at 5:30 for a 6:30 departure to see the dunes of Namib Naukluft National Park as the early light plays against the sand. Riding in a vehicle equipped for desert travel, we entered the world’s largest and longest park through the private gate of the lodge. Lined with dunes on both sides, Naukluft Park stands at 600 feet above sea level. We stopped at Dune 45, which most visitors climb by walking on the firmer sand along its windswept ridges. Following the footsteps of other climbers, three of us began our ascent of the 500- foot- high dune. It took us about an hour to reach the top, stopping along the way to catch our breath and to watch the surrounding moonscape carved by the winds; on the return we walked sideways downhill on the sunny side of the dune — an exhilarating experience indeed!

The Namib Desert is the oldest desert in the world; the dunes have developed over millions of years as a result of sand deposited into the Atlantic Ocean by the Orange River, then moved by current sand dumped back onto the land by the surf. Coastal dunes were shifted inland by the wind, which continuously reshapes them.

Driving about twenty minutes and then walking through deep sand, we reached Sossusvlei (“where water gathers” in Afrikaans.)This is an oval-shaped clay pan which fills with water after heavy rainfall, as the clay layers do not allow water to filter through. However, heavy rain only arrives every six years. Clay soil, hardened 900 years ago, has killed all the acacia trees, leaving only skeletons behind. Now the pan is called “dead vlei.” Dead tree trunks with branches reaching out in different directions transform the clay pan into a haunting sculpture park. A leisurely walk back to our vehicle allowed us to sight small creatures such as lizards in the sand.

Shade from a living acacia tree provided the well-deserved rest we needed. There were picnic benches and a picnic table, covered with a beautiful African cloth, where Joel and our driver treated us to coffee, tea, fruit juice, or our choice of fresh fruit. Considering the long drive back through the park, we returned to the campsite, as it was almost lunchtime.

Lunch was a choice of chicken curry or pasta. My steaming curry arrived in a small cast-iron pot to be served over a mound of rice. Preceded by a salad as appetizer, the satisfying lunch energized us for an afternoon at leisure, which I spent reviewing hundreds of photos of the morning adventure.

At 6 pm we gathered at the main lounge to watch a documentary on the Namibian genocide, a topic hardly known outside of Namibia. A tribal land until the late 1800s, Namibia became the object of imperial affection with Germany’s desire to expand to new lands. Huge tracts of land for cattle farming and the ox wagons of the native Herero were a great attraction. Convinced of their own racial supremacy, the Herero resisted the German presence, leading to an open war in 1903. Thus began the ethnic cleansing of the Herero; death and destruction swept across the land. Looking upon the Herero as savages, Germany felt the only solution was to crush them.

In 1904 huge supplies of artillery arrived from Germany with the goal of annihilating the Herero. Extermination became the official policy. All Herero were shuttled in trucks and cattle cars to concentration camps. Soldiers packed tribal skulls and bones to geneticists in Germany to prove that the black race was inferior and that black people were animals. White people who sided with black people suffered also. In 1908 the camps were shut down; the last of the Herero were sold to Germans as slaves. Defeat in WWI pushed Germany into devastation, forcing it to give up power to the British.

Germany apologized in 2004, which marked the centenary of the war in Namibia. The skulls and bones have been repatriated; reparations remain to be settled. At the end of this film, which introduced us to the first genocide of the 20th century, I left the room with a heavy heart and a lump in my throat. On the veranda the solitude and tranquility of the desert vista helped me recover my soul.

The next day required another early morning rise, this time for a hot-air balloon ride over the Sossusvlei at sunrise. As the only one in my group who had signed up for this optional adventure, I was picked up at the lodge in a 4x4 half an hour before sunrise and was barely able to see who else was riding. In the dark I rode into Naukluft Park with two others, who turned out to be an American couple traveling on their own. We arrived at an open field with two balloons ready for takeoff. I was escorted to the smaller of the two, which was for eight passengers — two people in each of the four sections of the basket — provided they were fit enough to climb in and out, stand for the duration of the flight and bend to a squatting position. The big balloon held sixteen passengers.

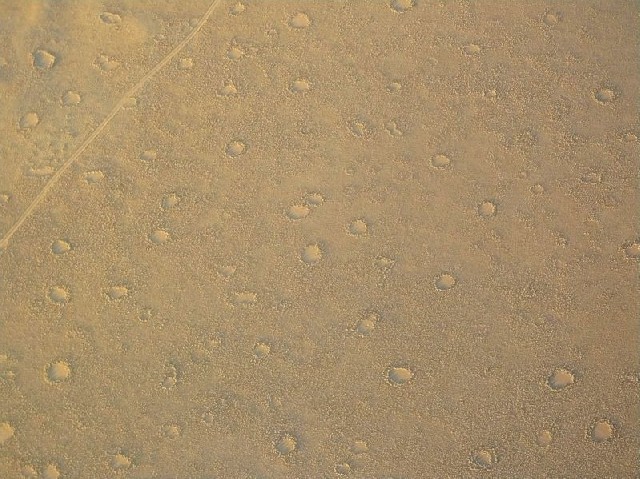

As the balloons rose, so did the African sun, revealing the red dunes all around. Our balloon went wherever the wind took it, changing speed from 6 to 41 km per minute, depending on the wind’s force. We drifted along the Naukluft River bed, lined with acacia trees, and hovered over mysterious circles on the sand’s surface, which I later found out indicated the presence of termite mounds underground. The majestic landscape of unending desert shifted from large panoramas of wind-carved craters and shadows under the changing light to close-up views of patterned ripples on the sand’s surface. At the end of the hour-long flight, we descended with the help of ground crew, who anchored the balloon.

After we landed, our magical experience continued a short ride away with a traditional balloonist’s champagne breakfast in the wilderness. We were treated to a sumptuous buffet, which included smoked zebra, salmon, a variety of cheeses, breads, and fruit, along with champagne, tea, and coffee. During breakfast our Dutch pilot provided information about Namib Sky Balloon Safaris, a company founded by a group who wanted to bring the magical aerial view of the Sossusvlei region to others. They had relocated 21 staff members with their families to the desert and opened a school for their children. To ensure high-quality education, two Montessori trained teachers — from Belgium and Spain — live on site.

By the time I returned to the campsite, the temperature had reached 44º C. After a quick shower I took a long nap. Once it cooled off, we left for the last excursion of our desert itinerary, the Sesriem Canyon, stopping on the way by a monument marking the Namibia Sand Sea as a World Heritage Site. Erected in 2013, the monument highlighted the criteria for its selection as: outstanding natural beauty; exceptional ongoing geological, ecological, and biological processes; and in situ conservation of species of universal value.

We proceeded to the Sesriem Canyon, a narrow half-mile-long gorge that plunges nearly 25 feet, creating a sheer cliff of limestone and sand. A variety of birds and wildlife make their home along its precipice. We descended to the bottom through a stepped rocky path and walked over to a shallow water reservoir, which provides much needed moisture for animals trying to survive in the harsh desert environment. At the end of our exploration we climbed back out the same narrow path, feeling ready for a well-deserved sundowner.

After dinner the dazzling night sky of the southern hemisphere beckoned me to my private roof top deck. Gazing at the starry night, I contemplated my birthday, which was the following day. It was also the day of our departure for Walvis Bay and the beginning of yet another discovery, Namibia’s Skeleton Coast.

(To be continued)