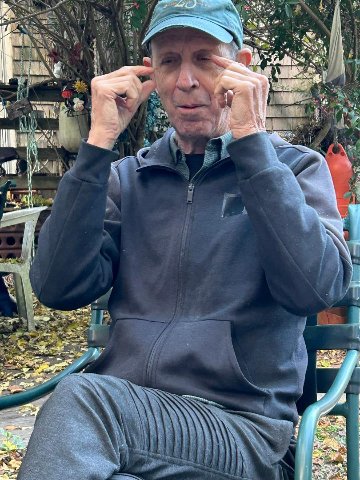

Provincetown Conceptual Artist Jay Critchley

Has Raised Millions for Charities

By: Charles Giuliano - Apr 17, 2025

In October 2024, we spent a week of research in Provincetown. My artist friend, Jay Critchley insisted. “I don’t fit in. This is a town of painters. That’s not what I do.”

At Fairfield University, a small Jesuit school, he majored in English with minors in religion and philosophy. Nothing prepared him for a remarkable career in social justice advocacy.

The long way around he “came out” as an artist by default. In 1981 he created a piece “Just Visiting for the Weekend, Sand Car Series #1.” A sister abandoned a Dodge which he encrusted with sand. Properly registered and insured it was parked at Macmillan Pier in the heart of Provincetown.

There was a competition to create a sign for Route 6 promoting Provincetown. He submitted the idea of a sand car parked by the highway. That notion was summarily dismissed. Jay does not take rejection lightly. Ignoring City Hall he parked the sand encrusted car, one of three, that remained on view through the summer.

He reasoned that no permit is required to park a car in a public space. Nor are there restrictions on how long it may remain as long as the fee is kept up to date. With a natural audience of tourists it attracted considerable attention. So much so that the police deemed it a public nuisance and tried to have it removed. Fearing a loss of its license the tow company refused to remove a parked and paid for vehicle.

With no prior art education or practice, inadvertently, Critchley had created an example of conceptual art. There was no other way to look at it. People and media began to refer him as an “artist.” That was difficult for him to accept. Having struggled to come out as a gay man he now was tasked with coming out as an artist. Both entailed complex identity issues and dramatic lifestyle changes.

The Critchleys were named 1958 Connecticut Catholic Family of the Year. His father was a patent law secretary for GM. He also raised and trapped minks which were skinned and processed in the basement. It was partly a hobby as well as a source of income. Jay helped to set traps but now cringes at the thought though forms of taxidermy figure in the work. There were pieces entailing fish skins retrieved from processing plants.

“We were a family of Irish Catholics with not one an alcoholic,” he recalls. “There were no child beatings that we know of. No abuse. No extramarital affairs.”

It was a large and remarkably functional, loving, and devoutly Catholic family. His sister Betsy was the victim of a serial killer. Other siblings include Eileen, Anne, Irish Twin Geri, Ceecee, Donny, Mark, and Kathleen.

The brood was routinely kicked out of the crowded house. Jay liked to play marbles but wasn’t keen on sports. By default he played four years of soccer which he wasn’t particularly keen on.

Early on he loved to perform with leads in high school musicals. He was the male voice in a family sextet which appeared on the popular Ted Mack Amateur Hour. They won the first week but were voted off the following one. Jay won a national essay writing contest. ”Dressed in uniforms they visited my home room to award me a prize,” He recalled.

The combined families summered at Uncle Cliff’s home on a small island off the coast of Connecticut. The ramshackle house needed constant repair. Jay helped and acquired skills with hand tools. That proved to be invaluable in later years. “I learned to work with my hands” he recalled.

In such a loving and supportive environment he strove to do the right thing. “At Fairfield I got a terrific liberal arts education,” He said, “That doesn’t happen anymore with a shift to preparing for professions and careers.” That background in critical thinking would provide a foundation for his work as a social justice activist. It was more useful and pragmatic than art school. It’s also part of why his work is difficult to define and appreciate. What its not is a compelling aspect of its wit and originality.

Often when discussing his absurdist projects there is a self deprecating wink and nod, a bit of chortle to confirm whether we are buying into the con. Like Christo and Hans Haacke it’s the complex process, legal and otherwise, that is integral to the work. Jay routinely takes on the establishment like battling for a patent for his product “Old Glory Condoms.” Created during the height of the AIDS epidemic he conflated the American flag and safe sex. Old Glory was never displayed at half mast. After an epic battle he secured a patent and the product reached global markets.

After college he was a Vista volunteer. When he returned home in 1971 he cohabitated with Alva Russell who he married in 1974. Their son, Russell, was born in Provincetown in 1974. The marriage ended in divorce not long after. Custody and visitation schedules were issues that went on for years. “They never spoke of me and told him that I was dead,” Jay said.

They later connected and Russell has three children by different women. Communication continues to be difficult.

When first visiting Provincetown Jay knew that something wasn’t right. It took time and years of therapy to find his sexuality and identity. That process came to be extended to confronting the pollution and corruption of major corporations with legal struggles subverting from within. For his projects and products he has created a number of corporations and is one himself.

In vivid detail much of his coming out and identity struggles are laid out in Peter Manzo’s controversial book “Provincetown: Art, Sex and Money on the Outer Cape” (2002). Knowing that I would talk about it with Jay I read it the week before we visited. It’s a scandalous page turner and I was surprised that Jay threaded through the book.

Describing him as a friend that he spent a lot of time with Jay said “Peter liked to pick fights and stir up trouble.” That was the case when Norman Mailer, a friend, turned on Manso when the biography was published. He also published a major biography about Marlon Brando. The son of Long Point artist, Leo Manso, Peter died at 80 in 2021.

“Peter grew up here then went away to Berkley for a decade,” Jay said. Upon his return Provincetown had changed and according to Manso not for the better. “He was a little guy who identified with macho men like Mailer and Brando.” Manso documented how Provincetown had been gentrified and “taken over” by gays both in real estate development as well as politically.

There was such outrage in response to the book that “People were mad at me for even talking to Peter.” Manso moved from Provincetown to the woods not far away.

I asked Jay how he felt about intimate details of his private life appearing in the book? “If you are an artist your life is part of the work” he told me. “So how can I object to that?”

Over the decades that I have known him it’s always interesting to hear about the latest projects. He has shown and performed globally. He updated progress on a project in Ireland.

“I went there first years ago” he said. “More recently I have been there four times. I went with family reconnecting with relatives. I have a large project. Friends procured for me a large tractor that I am covering with peat moss.” All these years later it sounds like an update of the “Sand Car.”

“When I got home I met for two hours with my son and his family” he said. Clearly hurt he said “I wasn’t asked a single question about Ireland.” He speculated about what that implied in what is a difficult relationship.

In 1975, having taken up residency in Provincetown, Jay joined the Drop-In Center, a free health clinic as program coordinator for its social services programs. The town had, since 1919, been under the care of the eccentric and incompetent Dr. Daniel Hiebert. Manso relates disturbing but hilarious anecdotes. With an influx of hippies there was a lapse in providing affordable health care. When Dr. Hiebert died Patti, the second wife of Ciro Cozzi the artist and restaurateur, founded the Center in a variety of inadequate venues. After several years it was precarious. As Manso reported “Jay Critchley scrambled like crazy, along with various board members to raise $75,000 to $100,000- then the need for the Center itself wasn’t as pressing as it had been in the past. Times had changed. There weren’t as many runaways. The kids weren’t coming in crazy on Quaaludes like they had before.”

After an epic struggle the Center was no longer sustainable. The experience, however, created a foundation for administrative and fund raising experience for the social justice programs Critchley later initiated. He struggled to survive on a salary of $6,500.

He formed a relationship with a staff member Dr. Doug Kibler. They bought a house in a densely populated working class neighborhood for $38,000. “Smartest thing I ever did. I could never be in town now if I hadn’t done it,” he said. “We might have been lovers for maybe a year. I was still not happy about being gay and I was not enjoying it.” As a lapsed Catholic, with emphasis he told me that “What I was doing was sinful.”

There was an amicable separation when Doug left during the summer of 1980 for graduate study at UCLA, Irvine. In the late 1980s Doug died of AIDS. With help from his family Jay bought Doug’s share of the property from Kilber’s estate. It entails a rental unit that, with years as a waiter, paid the bills. Today he has an income from Provincetown Compact. Primarily through the annual Swim for Life, the non profit has raised some $7 million.

Astrid and I were invited to visit for afternoon tea in his Provincetown Theme Park. The cluttered home is surrounded by twelve foot hedges. The back yard and its many artifacts remain much as we recalled from prior visits.

Deftly he guided us through the points of interest. A salvaged double seated out house is now a gallery. There were recycled Christmas trees, a grotto, the slowly deteriorating sand car with some of its original veneer. The highlight is a repurposed former cesspool. It has been modified as rental property.

Has anyone stayed there I asked? “Yes,” Jay said. “I have.” It has also served as a venue for underground theater and musical performances. “The audience stood over there,” he said pointing to an area which is now a garden. He paused to harvest a late season cherry tomato offering me one.

In the office gallery he showed us the vintage, legendary Miss Tampon Liberty. He had recently unpacked it and taken it to Ireland. In 1985 he established Tampon Applicator Creative Klubs International (TACKI). When walking the beach it was the most common item he encountered. Some 3,000 of them were fashioned into a gown that he wears for performances and protest demonstrations.

He was barred from wearing it during a committee appearance at the Massachusetts State Legislature. Not with the flow was a protest attempting reform of the Boston Sewage Outfall Pipe which dumped waste into the harbor. It has since been modified.

The plastic applicator is a product of Big Oil which has lobbied against developing a bio degradable version.

When we visited he had recently overseen the 37th annual Provincetown Swim for Life & Paddler Flotilla! It was inspired when Jay and some friends were challenged to swim from Long Point to the Boatslip. The event has grown to include global swimmers and sponsors.

Because of the ever increasing danger of sharks the swim is sited next to the shore as well as in a large pond. “Seals are now protected and have proliferated on the ocean side,” he said. “Sharks including Great Whites have swarmed to feed on the seals. Beaches aren’t safe and surfing is risky.”

Post holiday, January 7, 2025 marked the 42nd annual Re-Rooters Day Ceremony. It’s another Critchley event that has been modified. The initial concept was to stick Christmas tree stumps back into the ground. He tried to encourage families to use potted trees that could be recycled but that never proved to be viable.

The event has evolved into a ritual Valhalla burial for a single recycled tree. Jay fashions a rustic boat which with a communal participation is dragged to the beach. In ritual garb Jay leads onlookers in chants. The boat and its cargo is pulled into the water and set ablaze.

“Every year is different depending on the weather,” he said. “We have endured blizzards as well as enjoyed unseasonably balmy weather. It’s a wonderful bookend to the holiday season.” He noted that the Cape has ever more mild winters due to global warming.

There is a time to be born and a time to die. A time to plant and a time to uproot.

Passages and their rituals are an integral part of Critchley’s remarkable life and work. We spoke of legacy and what will come after. It’s obvious that artifacts like Miss Tampon Liberty and the Sand Car belong in major museum collections. But what of the ephemera cluttering his home and back yard Theme Park?

He hopes to keep it largely intact and has a plan. Now 77 he wants to develop the back yard into upscale condos. That would fund a foundation in his name to preserve the home and its content as a work of art. For the ever whimsical and inventive artist the end of life is potentially another and final conceptual art piece.