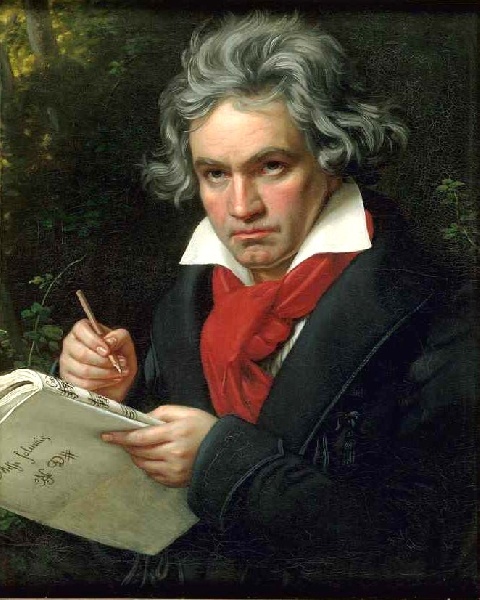

Beethoven, Fidelio, part II: a Major New Recording by Colin Davis and the LSO

A fresh approach to Beethoven's Fidelio

By: Michael Miller - Apr 19, 2007

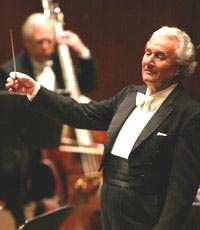

Beethoven, Fidelio, Op. 72 (1805-14)Sir Colin Davis conductor

Christine Brewer Leonore

John Mac Master Florestan

Kristinn Sigmundsson Rocco

Sally Matthews Marzelline

Juha Uusitalo Don Pizarro

Andrew Kennedy Jaquino

Daniel Borowski Don Fernando

Andrew Tortise First prisoner

Darren Jeffery Second prisoner

London Symphony Chorus

London Symphony Orchestra

LSO Live 0593, recorded live in May 2006 at the Barbican, London

Sir Colin recorded Beethoven's Fidelio once before in 1995 for BMG/RCA in a co-production with Bavarian Radio. His cast was most distinguished, including Ben Heppner, Deborah Voight, and Thomas Quasthoff, but I can understand why he might have been dissatisfied with it. The acoustics of the Herkulessaal in the the Munich Residenz are notoriously dry, and the close miking and probable artificial reverberation resulted in a flat, congested sound-stage. Ultimately, however, if you compare the two recordings, Sir Colin has rethought Fidelio from the ground up, and last year's performance at the Barbican is totally different from the Munich recording—and every other performance I have heard. He has achieved a fresh insight into the work and pentretrated into Beethoven's complex score and simpler, but noble intentions in a revolutionary way.

In essence, Sir Colin has let go of the energetic momentum which conductors often unleash in the overture and allow to build in a linear fashion towards the excitement of Florestan's liberation and the final scenes. While Klemperer stands in a monumental category of his own, this is as true of Bruno Walter in 1941 as it was of James Levine's last month, although Levine developed his with a somewhat intellectualized contrasting pattern between very fast and very slow tempi. This corresponds generally to the shape of Beethoven's Fifth Symphony, and stresses the symphonic aspects of the opera, but it also allows one to sweep over the early scenes of domestic comedy, which embarrass some critics, since their touches of vulgarity and triviality are so unlike the exalted sentiments of the conclusion. Much of the music, also, reflects Beethoven's earlier style of 1804-05, when he was composing the first version. Sir Colin shows no sign of condescension, either to the dramatic scenes or the music, and delves into the beauties of the score, as if he were just about to turn around and give us a splendid performance of Beethoven's Second or Fourth.

Davis' interpretation is shaped by the dramatic pauses which are suc a fundamental part of Fidelio's dramatic structure, a Furtwänglerian sense of the overarching shape of phrases and entire passages, a keen sense of the dialogue between the singers, chorus, and the orchestra, as well as the shifting and developing moods of the characters and the music. He underscores the importance of these pauses in the first bars of the overture, where the following slow passage flows organically from the opening tutti and the ensuing pause towards the faster, flowing section which follows it. Throughout the opera, the texture is extremely clear, there is a wealth of orchestral detail, and as a recording it all sounds natural: I imagine we are hearing pretty much what a member of the Barbican audience heard from halfway back in the stalls. With all these qualities in play the orchestra becomes part of the drama, sometimes telling the story, sometimes painting the thoughts of a character, sometimes serving as the voice of one of the ideal concepts which also act in the drama: hope, consolation, duty, Providence, freedom. We listen with the awareness that Beethoven was actually rather good at using his orchestra, singers, and chorus as dramatic storytellers. Davis makes the most of Beeethoven's varied strophic reprises, not only bringing out variations of harmony and scoring, but making them expressive of developments in the characters' emotional response to situations and events through phrasing, above all in the vocal parts.

It is also significant that, after his Munich recording with two protagonists with big voices and reputations, one, Ben Heppner, of a particularly Wagnerian sort, he has sought out fine singers with not such obviously powerful instruments. There is a tradition of casting Leonore with a Wagnerian soprano, and some, like Kirsten Flagstad, have been magnificent in the role, but it is not the only valid approach. I noted already in the first part of this double review that Christine Brewer, while she certainly is endowed with a large voice, is not by any means a Nilsson or a Flagstad. One could say the same about John Mac Master. It is clear that Sir Colin wants his cast to sing as an ensemble.

In the first two numbers, Marzellina's aria and her duet with Jaquino, Sir Colin sets off with sprightly pace and phrasing. The lightness he brings to the music contrasts effectively with her agitated state of mind and minor key. Jaquino, when he enters, is open and affectionate with little trace of any boorishness. Their irritation with one another develops over the course of their interaction. In her spoken dialogue Sally Matthews gives us an earthy, even vulgar Marzelline, who is only slightly at odds with her elegant singing. With Leonore/Fidelio's entrance the tempo becomes broader, the melancholic strain more prominent, and the orchestral textures richer. The quartet ("Mir is so wunderbar") is extremely broad, but enlivened with crisp, expressive phrasing and a sensitive awareness of the cross-rhythms which emerge as the canon unfolds. Marzelline's entries are a wonderfully hushed pp, and the singers' interaction with the orchestra is a revelation—features which add color to Rocco's much-maligned aria ("Hat man auch kein Gold beineben"), as ably sung as acted by Kristinn Sigmundsson. In the ensuing dialogue the defects in Christine Brewer's German become mildly distracting, even comical, in her more pathetic lines, but it is not nearly so noticeable in her sung parts. (Her American accent was a little less prominent in Symphony Hall. Perhaps she has worked on the problem.)

The march, to which Pizarro and his men enter, begins with a sprung liveliness, the rhythms sharp, the textures clear, and the instrumention full of color, becoming more ponderous as Pizarro's threatening presence makes itself felt. Sir Colin sees it as a play of contrasts, and at points its characterization of Pizarro's arrogance is almost satyrical. When the vivid Pizarro, Juha Uusitalo, launches into "Ha, ha, welch' ein Augenblick!" he takes a deliberate pace, as full of violence as fury, and all of Beethoven's wealth of orchestral detail and interplay makes itself heard. When he turns to Rocco in "Jetzt, alter" the tempo is also moderate, allowing a nuanced interaction between the governer and his jailer, concluding with wonderful detail and texture in the orchestra and striking sonority in the bouble basses. Christine Brewer brings off her "Abscheulicher!" not only with the fine energetic scorn of her BSO performance, but with an added measure of poise in her phrasing and a firm grasp on the sequence of Leonore's emotions. The orchestra's finely shaped phrasing and neat articulation reflects Davis' classical view of the number, harking back to the grand arias of eighteenth century opera seria. The LSO horns acquit themselves especially well.

The great three-part finale begins with a ghostly ppp, as the prisoners emerge from their cells. The tempo is very broad. Sir Colin takes much care with the dialogue between the chorus, soloists and orchestra and the finely characterized and contrasted solos of Andrew Tortise as the first prisoner and Darren Jeffery as the second. The orchestra is quite prominent here, and, to my ears at least, something strange happens in the recording of the chorus. In places it seems to recede into the distant background and lapse into an indistinct sound—the only serious flaw in otherwise exemplary recording. After the flowing louder section, the reprise is even more wraith-like than the first statement. As Act I comes to its hushed conclusion, Davis takes special care to keep all elements in balance: the voice leading, texture, and color of all elements.

The introduction to Act II is flexibile in meter and phrasing, perhaps the most Furtwängler-like moment in the performance. Canadian tenor John Mac Master as Florestan begins his "Gott, welch' Dunkel hier!" without any exaggeration of his first note. He takes care to portray his character as a noble, even heroic man, who is weakened almost to the point of death by his imprisonment. His voice warm and humane, with a soft, even vulnerable surface, recalling Julius Patzak in Furtwängler's 1950 Vienna recording, and he responded to Sir Colin's concentration on dialogue with the orchestra with energy and passion, most powerfully at "Und spür'ich..." and in his angelic vision. The dark, threatening sonorities of Rocco's duet with Leonore were most effective, and the ensuing trio, when Florestan awakes again ("Euch werde Lohn"), was distinguished by Mac Master's powerful overarching lines over Davis' broad tempo and strong syncopated accents. The quartet with Pizarro ("Er sterbe!") begins slowly with measured phrasing and builds up to a ferocious outburst and a rush forward, until the first trumpet call brings the action to a halt.

Throughout these final numbers, Davis' loving attention to the details of Beethoven's inner voices and instrumentation brings out the composer's rich treatment to full advantage, especially in the wild "O namenlose Freude," and the solid, jubilatory "Heil sei der Tag." Interestingly, the even larger chorus with its complement of townswomen is recorded beautifully here, with no trace of constriction at the end of the first movement. Polish bass Daniel Borowski is a human but powerful presence as Don Fernando, his phrase "Tyrannenstrenge sei mir Fern!" mostly effectively point by an accented chord in the horns. Sir Colin makes the most of the dramatic pauses, which as so important in the passages following the trumpet call and culminating in the final stanza of "Ach, welch' ein Augenblick!" Sir Colin brigs the curtain down with a solid, energetic, and very grand treatment of "Wer ein holdes Weib errungen" in which no detail is lost, not Mac Master's eloquent phrasing, nor the careful balance between finely articulated tympani and wind phrases, nor the piccolo, nor any of the inner orchestral detail.

Sir Colin's interpretation, his singers' intelligent contribution, and the alertness and musicality of the London Symphony, which is approaching the very top ranks, never let us forget, even in the privacy of home, that we are listening to a stage work with an extraordinarily developed orchestral part—the most elaborate yet developed—not a symphonist's clumsy approximation of an opera. Making a break with his earlier recording, he communicates his extraordinary insight into Beethoven's writing, both in its orchestral and dramatic aspects. Any collector or anyone new to Fidelio who wants to understand it better should own this recording, because it documents a vision of the work, which is most characteristic of the present moment.

If you are a long-time collector, you will find yourself comes back to it often. If this is your first recording of Fidelio, others will eventually join it, above all Furtwängler's studio recording with Martha Mödl (1954) and his live performance with Kirsten Flagstad and Juilus Patzak (1950). Under Otto Klemperer, who conducted a famous radical production during the Weimar Republic, two extraordinary performances survive, one from the studio and another from Covent Garden in the early 1960's, one with Christa Ludwig, the other with Sena Jurinac as Leonore, both with Jon Vickers' great Florestan. There are two recordings available under Karl Böhm, who had a great mastery of the work and often conducted it at the Metropolitan Opera. So did Erich Kleiber, whose radio performance is probably the best source for Birgit Nilsson's Leonore. More recently Bernard Haitink and Nicolaus Harnoncourt have brought notable understanding to the work and assembled first-rate casts. The DVD of Haitink's 1979 Glyndebourne performance, directed by Sir Peter Hall, is particularly worth seeing. Harnoncourt's interpretation comes close to the present recording in insight, more "authentic" in sound, exquisitely sung, but less compelling dramatically. Finally, you won't want to miss Colin Davis' 1996 Munich recording, which I have already compared unfavorably to the new one, but which contains the interpretations of three of the most important singers of the present day, Deborah Voight, Ben Heppner, and Thomas Quasthoff, as well as a probing interpretation of the Leonore Overture No. 2 as a filler.

If some of the dramatic situations and the rhetoric of the libretto make us cringe or chuckle on occasions, that is nothing new. Fidelio was to a certain extent a fairly straightforward adaptation of a model belonging to a particular genre of French opéra comique, the so-called "rescue opera" (see my Fidelio, Part I) which developed over the second half of the eighteenth century and reached its peak in the turbulent days of the Revolution. This type and French opera in general became wildly popular in Vienna, something of theatrical backwater during the first years of the nineteenth. The Empress adored it, and Beethoven saw a distinguished example of it in Lodoïska by Cherubini, whom he considered the greatest opera composer of his time. (This excellent work was once available in a fine live recording under Muti from La Scala, now unfortunately withdrawn. It certainly merits another revival on stage and would be perfect for the Bard Summer Festival.) In its wake, it took Fidelio almost nine years and two revisions to become a success. By then it was the eve of the Congress of Vienna. As popular as Fidelio remained, its genre soon faded into oblivion in Germany, where composers became absorbed in creating a characteristically German form of opera. In this way, Fidelio is a fossil. Beethoven is surely to blame for some of its peculiarities, but his provincial milieu and his transitional moment share at least as much. On the other hand, the work continues to move us, not only because of Beethoven's music, but because it encloses a distillation of the revolutionary spirit which, however vague, adulterated, or even inverted, permeated the air in the years following the American and French revolutions as well—contained above all in that dramatic pause in the second act, followed by the famous trumpet call.