Route of the Maya: Part Two

El Salvador to Honduras

By: Zeren Earls - Apr 19, 2016

The main trip of the Route of the Maya began in San Salvador, located in the Boquerón volcanic valley of El Salvador, which is Central America’s second smallest country, yet home to 25 active volcanoes. We met the four new members of our full group of 16 at the Crown Plaza hotel, where we spent two nights to get acquainted with the capital city.

On the way to tour San Salvador, our local guide, Carlos, gave us some basic facts about his country. El Salvador is divided into 14 provinces, based on land ownership by the 14 European families who originally settled there. Of the total population of 7 million, 1% are indigenous, 9% European, and 90% mestizo. 2½ million of the country’s 7 million people live in San Salvador; several hundred thousand of those are street vendors trying to make a living, due to 18% unemployment. Most of El Salvador’s economy is supported by people who work outside the country and send money home. 2.8 million of those work in the US; others are in Canada and Europe.

Starting at the Museo de la Palabro y la Imagen, dedicated to preserving the culture and history of El Salvador, we were met by a local resident, who shared his experience of having lived through the armed conflict and played soulful songs for us on his guitar. The museum’s exhibits of photographs, publications, and memorabilia offered diverse perspectives on El Salvador’s tumultuous military history and how it had affected the people. The civil war had finally ended with a political solution negotiated on January 16, 1992, transforming El Salvador into a society in search of peace, social justice, and equity.

Acquainted with the country’s history, we then visited the National Cathedral, which houses the tomb of Archbishop Oscar Romero, assassinated in 1980 for speaking out against human rights violations. The Cathedral faces Plaza Barrios, also known as the Civic Plaza, with a bronze statue of former President Gerardo Barrios on a horse. The statue stands on a granite pedestal depicting battle scenes and displaying the shield of El Salvador. President from 1854-1863, following 1865 elections, Barrios was tried and executed for his liberal views on August 29 of the same year. He was granted the tittle of "National Hero" in 1910 for protecting the rights of farming communities and protecting Central America from foreign invasion.

A short walk away is the El Rosario church, which stands in contrast to its colonial surroundings. What looks on the outside like an office building with unusual architecture has a stunning interior with undefined walls and kaleidoscope stained-glass windows. Designed by sculptor Rubén Martínez and completed in 1971, the church is built of recycled materials and lit by natural light. During the civil war 21 people were killed for rallying by soldiers at the entrance, where bullet holes in nearby concrete walls evidence the violence. Many of the statues within the church are made from civil war guns that were melted down for the purpose.

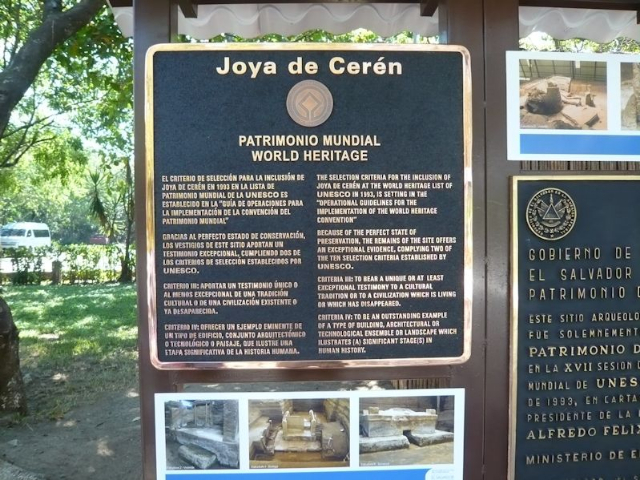

Thirty minutes from San Salvador is the archaeological site Joya de Cerén (Jewel of Cerén), a Mayan farming village preserved intact under layers of volcanic ash, referred to as the “Pompeii of the Americas” and now a UNESCO World Heritage Site. It was discovered in 1976 during a government agricultural project and is still being excavated exclusively by Payson D. Sheets of the University of Colorado at Boulder. We visited the site, close to the border with Guatemala, starting at the museum, which houses objects found during the excavations and photographs of the digs in progress. A walk through the site, which dates from the Mayan classical period (200-900 AD), revealed a village life characterized by small living quarters, a communal steam bath, gardens adjacent to a kitchen with open fires and chimneys to let out the smoke.

Just before we crossed the border to Honduras, we stopped for lunch at Los Remos, a rustic restaurant with a lovely lake view and mountains in the distance. Throughout the trip our choice of main dish – from a selection of chicken, beef, fish, or vegetarian – was always called in ahead of time by Ivania. The first course – often soup – and dessert were served as part of a set menu for all meals when we were not on our own. The house specialty at Los Remos seemed to be chocolate cake, made with one part cocoa to five parts sugar and topped with sliced almonds – super-sweet, yet delicious.

At the border was a long line of trucks waiting for clearance, as all items have to clear customs, with duties paid accordingly. While we were waiting for passport clearance, Ivania bought potatoes from a nine-year-old boy, who was working after school to bring money to his mother. He was in third grade and one of ten children, the youngest of whom was three. For a Mayan family the average number of children is seven, based on their belief system, which emphasizes procreation. They believe in perpetuating their kind by teaching children survival skills, which carries more weight than sending them to school.

Finally we got clearance to cross the border and headed to the town of Copán Ruinas, gateway to the famed Copán ruins. One’s first impression upon entering the town is the visible presence of armed security in front of banks, gas stations, fast-food stores, and markets. People feel safer patronizing places where there is security. Upon arrival at the Clarion Hotel, we were offered a welcome drink with rum. Made from sugar cane, Honduran rum claims to be the best. The hotel, where we spent two nights, was charming, with its interior courtyard around an attractive colonial fountain and tropical plants.

In the morning we set out for the ruins of Copán, the most elaborate of all Mayan cities and designated a UNESCO Heritage Site in 1980. There is a large image map of the city in the Institute of Anthropology and History, where wall texts provide an overview of environmental effects on the site and ongoing conservation and restoration efforts. Walking down a trail, we were then immersed in the natural world of the Maya. Tall ceiba trees reached toward the sky, while scarlet macaws on trees or feeding by their man-made homes showed off their vibrant colors.

The scarlet macaw was a sacred bird for the ancient Maya. It represented the powerful god of the sun, Kinich Ahaue, in flight between earth and heaven. Its feathers were used to decorate the headdresses of high-ranking officials. Efforts to conserve the scarlet macaw are thus extensive and include designing and installing nests, monitoring their diet, and optimizing breeding conditions.

The city-state of Copán is organized in groups. In the center is the Great Plaza, flanked by the imposing “Acropolis”, the Hieroglyphic Staircase, and the ball court. The Acropolis is a raised royal complex of overlapping step pyramids, plazas, and palaces. By digging a series of tunnels into the center of the Acropolis, archeaologists have discovered its previously buried versions associated with the earliest rulers; kings represented God on earth and lived in special palaces, high up and away from the dwellings of commoners.

The Hieroglyphic Staircase is so named because of the over 2000 glyphs, or symbols, carved into its 63 stone steps, making it the longest Mayan inscription. It recounts history since the beginning of the dynasty founded by Yax Kuk Mo. Precise measuring and recording the dates of events, such as the reigns of rulers or the construction of monuments, were of utmost importance to the Maya, who thus created elaborate sacred calendars. In front of the stairway is a large carved stone column, depicting the ruler at the time of the commission in 756 A D.

A walk among the ritual altars scattered about the Great Plaza and the large carved stone columns called stelae, placed near them around processional ways provided a wondrous experience of viewing ancient sculptures. The fantastic stelae are narrative portraits of kings performing rituals and milestones in the calendar; most are of the 13th dynastic ruler. The Maya had two calendars: one, the Haab, for rituals and one secular calendar, the Tzolkin.

Houses for high-ranking families are clustered around residential courtyards. The buildings have tumbled into heaps because of geological movement, as some are located in very unstable areas and their foundations have sunk below their original level. While the limestone available in the area provided the inhabitants with construction material, it also made the hillside an unstable place to construct heavy masonry buildings. With the fall of the dynasty in AD 822, the buildings were suddenly abandoned. Since then fantastic trees have taken root, keeping the elaborately decorated structures from sinking further.

At the end of our visit we stopped at the park gift shop, where I purchased a T-shirt with Maya numbers and, from a child vendor, a traditional doll out of corn husks made by Mayan women. My choice for lunch at a local restaurant was fish with loroco sauce, which is made from the unopened buds of the loroco flower, used for flavoring and adding a nutty taste to dishes.

Some in the group then opted for horseback riding in the country, while a few of us stayed behind to explore the colonial town of Copán Ruinas, with a population of about 3000, most of whom depend on the tourist economy. As in all colonial towns, the centerpiece of the town square is a Catholic church. Along the cobbled side streets, vendors displayed stone or ceramic replicas of statues and other objects found among the archeological ruins nearby.

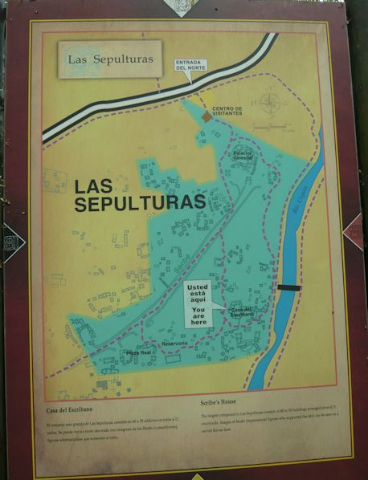

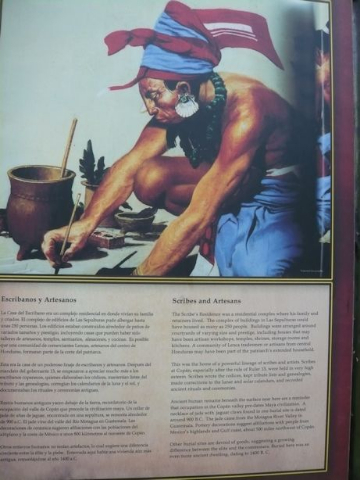

On our way to Guatemala in the morning, we stopped at another part of the extensive ruins of Copán – Las Sepulturas, a residential complex mostly for artisans and scribes. Buildings here were arranged around courtyards of varying size and prestige, based on the power of each family’s lineage. Scribes wrote codices (Mayan books) and kept genealogies. They were also responsible for adding the date, the name and a list of achievements on each house of the elite.

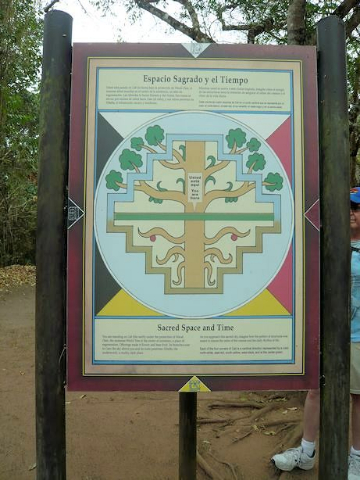

As we walked about, we came upon a billboard with the heading “Sacred Space and Time” and displaying an image of a large “world tree”; the tree was depicted with a patterned structure, ensuring the order of the cosmos and the daily rhythm of life for the Maya, who believed in a series of worlds created and destroyed by Gods. Each of the tree’s four corners pointed to a cardinal direction represented by a color: white for north, red for east, yellow for south, and black for west, with green at the center of the tree, which was also the center of existence and a place of regeneration. Offerings made the tree flower and bear fruit; its branches soared to the sky and its roots penetrated the underworld – a dark, murky place.

Intrigued, I looked forward to continuing overland to Guatemala for further discovery of the remains of this enigmatic civilization of Mesoamerica scattered across the 1500-mile-long ancient trade ring known as the Ruta Maya.

(To be continued)