The Believers at MASS MoCA

States of Denial

By: Gregory Scheckler - Apr 23, 2007

"The Believers isn't about "belief" per se, but rather about the believers themselves, whose deeply-held personal truths fly in the face of skepticism, irony, and often, reason."

- Promotional texts for the exhibit.

"The adversary says that he does not want so much science... to this it is replied that nothing more deludes us than to place faith in our own judgment without any other reasoning, as may be proved by the way in which experiment is always the enemy of alchemists, necromancers, and other simple minds."

- Leonardo da Vinci

Slapped together by curatorial duo Nato Thompson and Liz Thomas, The Believers promotes bland whimsies that often deny the value of critical thinking and that sometimes misrepresents the artist's intentions. A superb exception to the exhibit's numbness is sculptor-engineer Theo Jansen. Less exciting are Genesis P-Orridge/Lady Jaye/Breyer P-Orridge, CariannaCarianne, Icelandic Love Corporation, Yoshua Okon and Fritz Haeg, Panamarenko, Sister Mary Corita, Jonathan Meese, Emery Blagdon, Walter Cassidy, Roger Davis a.k.a. Witch Vortex, sound artist Erkki Kurenniemi, and Bas Jan Ader who disappeared while trying to cross the

In contrast to the majority of the show, sculptor Theo Jansen's kinetic sculptures show a great deal of technical cleverness. In motion, the sculptures are quite intriguing 'life forms' and beautiful to watch. Be sure you check out the videos (online at http://www.strandbeest.com). The curators chose to believe Jansen's sculptures really are life. I found this to be a rather bizarre claim and wondered if they were misrepresenting Jansen's intent. So I contacted the artist and asked him if he uses the idea of 'life' in quotes, as an artistic analogy. Does he believe his artworks literally are life?

This is the response he wrote to me (English isn't his native tongue): "One of the criteria of life is reproduction. I try to but I am not yet able to let the animals reproduce. Making life in my world means a fairy tale. I am the Don Quixote who wants to make life. I fight against the storms and the tides. On the other hand: I want to make functional animals. So a fairy tale based on reality. If you art as a product of imagination, it is life as an artistic metaphor. I think art is an institute. I make things not especially art. But after all an art institute like MASS MoCA is a good way to show what I have done and to inspire people."

It's fair to conclude from this that Jansen thinks of his work more as an engineering and design project, than as art or literally as new life – the sculptures are intermediate steps towards his larger goal of creating autonomous creatures. Sadly, the curators chose not to detail Jansen's working methods, how his engineering works, what computer programs he designs with, etc. This demonstrates how the exhibit grazes across a smorgasbord of belief, not providing in-depth explanation of reasoned design. Thankfully, there's much online where you can learn about the computer programs that Jansen uses to help refine his designs using evolution-like algorithms.

Although the curators write that Jansen's work has no parallels in robotics today (being wind-driven and made of pvc pipe), there are good contrasts with numerous seemingly life-like, interactive robots and computer software. More than a few robots, like Jansen's, were borne of pneumatics: spidery 'Boadecia' from MIT Media Labs; or the various pneumatic 'air muscles' from older robot groups, like Shadow Robot Company, whose robotic human-like hand is legendary. Software simulations of life include the popular Sims, as well as the increasingly popular Second Life website, which is a virtual environment where you create and direct your own virtual persona. As art, numerous artists use evolving algorithms for computer graphics: in the 1990s Karl Sims created life-like artforms, and software that created graphics based on the audience's aesthetic selections rather than an ecological natural selection. These are similar to Theo Jansen's computer 'worms.' Others have, like Jansen, taken a low-tech approach to their kinetic sculptures built out of easily available hardware-store supplies, such as Timothy Hawkinson.

Pop-culture robots are mechanical pets such as Furby, Sony's Aibo dog, etc. One of the newest, Ugobe's Pleo, is a mini-dinosaur. According to its manufacturer, like Jansen's work, it too is a designer 'lifeform.' It includes 38 sensors that detect the world, as well as 8 microprocessors that perform up to 60 million calculations per second. It has smooth skin, it can sneeze, howl, sleep, snuggle, walk and its software is completely upgradeable (search online to find videos of Pleo). It requires electrical power whereas Jansen's inventions are far larger in size, and many move themselves on the basis of wind and air pressure, not electricity. But as art, all of these are dramatizing the science-fiction idea that unusual new robotic or other life-forms might be created. Jansen's beasts are a lot more interesting to watch than the toys– but in terms of interaction with their environment and with people, they're not yet as computationally sophisticated as toy robots. The price of digital video and photography has dropped so dramatically that now these image-creation technologies are widely available. Will the same happen with robotics?

This disconnect between what's commercially available as a toy and what artists can afford to do as art is a significant problem for experimental artists today. The more complex the computing and engineering demands of an artwork, the more financial resources will be needed. Because the finances needed for significant computing or robotic development are out of reach of most individual artists, those who experiment with these forms run the risk of making work borne out of cheaper, older parts or lesser software than what the bigger research groups use. Thus the art can almost instantly appear outdated and outmoded in terms of its technology. Yet, as Jansen has, the individual may be able to take fascinating aesthetic risks that corporate financiers wouldn't take. Let's hope that future upcoming designer 'lifeforms,' don't all like Pleo look like cutesy Disney-style animatronics.

I've covered Theo Jansen's work and it's contexts in detail here because it is probably the only work in the exhibit that's really worth the investment of time. Another exception to the exhibit is Sister Mary Corita's posters. These mix pop-culture, hippy sayings, and open-ended Bauhaus-style graphic design. The prints were meticulously crafted. Personally I found the sparseness of their designs to be somewhat of a relief compared to schizophrenias found elsewhere in the exhibit. Here too, audiences are provided little context for Corita's work.

Parallel to denying the artist's and the art's artistic and cultural contexts is the curator's decision to position scientific understandings of the world as if they were beliefs. Their brief exhibit guide and introductory wall panels say this kind of thing "Just as spiritualists believe in forces that operate beyond the material plane, scientists believe in phenomena that they cannot always fully understand and document – each case superceding the limits of empirical knowledge." That statement, in a nutshell, is the legacy of crooked deconstructivist thinking that permeated so much trendy art, art theory, and museum studies throughout the late 20th Century. Probably the curators believe contemporary science is just another of Kuhn's so-called paradigm shifts. They couldn't be more wrong.

I'd like to know exactly what phenomena they claim the scientists believe – the theory of evolution? It's now so rigorously tested that it's about as undeniable as understanding that H2O is a good way to describe water. Quantum physics? You can't see such tiny matter directly. But it's now so well-tested that as a group of theories it really does very precisely describe how extremely small forms of matter interrelate; it's not a belief, it's sets of rigorously useful descriptions. Yes, some aspects of these theories are incomplete. But these newer scientific models of the world are far less incomplete and far less wrong than any prior century's understandings. Why? The sciences center on numerous ways of testing and explaining how the world works, seeking natural not supernatural causes and properties.

The spiritualist seeks supernatural causes which often aren't testable at all – and therefore, highly suspicious as knowledge or as explanation. You have to believe in the supernatural, because no one's ever actually verified that it really exists. Like Leonardo before him, the sharply political artist Goya [1746-1828] penned "Fantasy abandoned by reason produces impossible monsters: united with her, she is the mother of the arts and the origin of their marvels." What's really astonishing is that some artists and their curators in the 21st Century could make and promote – on purpose – the same basic errors of untested belief that Goya, numerous earlier artists, and many proto-scientists worked against. Belief may well be fundamentally important to humanity – we all need hope, and sometimes must simply trust that the world will turn out okay. But what The Believers curators and most of its artists seem not to understand is that false belief, false because unrelated to the real world and focused away from it, often has disastrous results for cultures and individuals.

Just what's the danger with the artist's beliefs? Many supernatural beliefs are consumer frauds, snake-oil medicine, like tv psychics who prey on our desire to regain contact with lost loved ones. Based on deranged versions of some beliefs, many cultists become violent (cultist's poison gas in

Nevertheless, waylaid mystical beliefs alone are not necessarily the problem with the exhibit. Some belief-laden and belief-motivated art is spectacularly aesthetic. For example, Bernini's Capella della Madonna del Voto (c.1659) in the Sienna Cathedral,

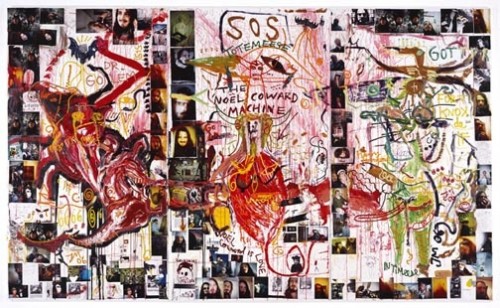

Jonathan Meese's gigantic paintings are good examples of this problem. Here's an artist with a seemingly good idea to create a new kind of 'total art' – he calls it a gesamtwerk – that moves from performance, sculpture, painting, digital photography, video, and drunken dance all at once. But why are the results, his paintings and sculptures, so damn ugly? Bernini's chapel combines numerous art forms, rituals, and myths all in one seamless way too, yet it's gorgeous. A more contemporary example would be the Rothko Chapel (see website at http://www.rothkochapel.org/ ), containing Rothko's meditative abstract paintings – all gorgeous. Another example would be the transcendental paintings of Alex Gray, which contain dopey New Age symbolism but also a truly astonishing, exacting command of the painter's craft. So the beliefs aren't exactly the problem. Rather, the problem is how The Believers contains too much visually impoverished, easy-to-make art… I've had enough of it. Meese's anti-aesthetic, graffiti approach is lame, nowhere near as visual as the graffiti-pop paintings of Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960-1988). Meese's approach and its cognates are becoming increasingly démodé and quite out of sync with vast numbers of today's artists and art students who prefer the value of well-crafted, beautiful, intensive aesthetics.

Dead artist Emery Blagdon's wire sculptures and paintings on barn planks are somewhat intriguing. As for symbolic content, Blagdon reportedly "believed that his intricate constructions… exuded healing energy fields, a phenomenon that he did not, and could not, explain." There's a simple reason why he couldn't explain it. The so-called energy fields didn't exist. His beliefs were mistaken. Instead of rigorously demonstrating that they exude healing energy, Blagdon obsessively made more paintings and wirey thingamajigs which now after his death are in the hands of art collectors turning a buck off of his odd obsessions. Such profiteering over recently discovered 'outsider artists' is so effective that there are counter movements, such as the faux-naïve art that was trendy a few years ago in many graduate schools, in response to recently discovered fantasias by Henry Darger (1892-1973).

Like Blagdon, supernaturalists usually claim that their faith, their magic spells, their rituals are alternative ways of knowing and interacting with or experiencing a special world. Indeed The Believers curators agree – they've upgraded the artists' beliefs into "personal truths". But do they actually discover any truths? Probably not. For the most part the artists aren't interacting with the world so much as with their own belief-laden imaginations, suckling their favorite Imaginary Friends. And yet they claim to know. But what precisely do they know, except more make-believe? In Leonardo da Vinci's time, the con-artists, profiteers and believers were the alchemists, necromancers, and astrologers. Today it is creationists and 'intelligent-design' theorists, cultists, 'energy healers,' contemporary shamanists and sorcerors, tv psychics and the like – all refusing to test belief and its predictions with careful experiment, instead favoring and promoting their beloved imaginings.

Other bland craftwork includes low-resolution video-screens and badly-crafted calligraphy (CariannaCarianne and others), sonically bereft and sarcastic music videos (Icelandic Love Corporation, Erkki Kurenniemi), post-punk nightclub glue and glitter with mirrors and taxidermy (P-Orridge; I would've liked the taxidermy heads-n-knives if the artists had edited everything else away), icky grainy poorly exposed and non-composed photos (Bas van Ader, Icelandic Love Corporation, Walter Cassidy), and dull maps that misunderstand genius (Okon & Haeg). Fundamental to The Believers is the repetition of lame, un-crafted artworks, the likes of which are frequently seen in contemporary art museums, every Whitney Biennial, and numerous other junk-shops. My wife likes to remind me that every once in a while you can find a gem in a junk shop. But to me the exhibit looks a lot like what's been presented as contemporary art for at least three decades now. Maybe it's time for artists and curators to find new ways to be contemporary.

A friend wondered what would happen if the museum put on a show titled The Skeptics, opposing the current exhibit. He thought that a skeptic's show would bore audiences, and just wouldn't be weird enough. I disagreed. From my view, it is the Bucky Fullers, the Carl Sagans, Daniel Dennetts and Richard Dawkinses of the world who are incredibly insightful visionaries. Their kind of philosophical naturalism, at the roots of the sciences and many kinds of arts, creates wonderfully engaging products, information-rich, and precise. The artistic products of such inventiveness, such as photos from the Hubble Space Telescope, can be astonishingly beautiful – even when, like so much of the art in the exhibit, such visual products are intended to be documentary results of process rather than purely aesthetic.

Will contemporary art always have to be stupider than the Hubble Space Telescope's results? Why aren't artists, like scientists and engineers, placing their belief in the power of contemporary philosophical naturalism and its ability to comprehend and contend with the world, instead of placing their belief in ridiculous art theories that cannot test and investigate the world? Unlike their counterparts in the sciences, large segments of the arts radically departed from philosophical naturalism in the early 20th Century. You could track The Believers tactics back to various Surrealist methods, and Dada, or earlier beliefs of the Romanticists, or the art-theoretical influences of Freud and Jung and other early 20th Century claptrap. In-depth historical studies of supernatural beliefs in Modern art include Richard Lofthouse's Vitalism In Modern Art, C. 1900-1950: Otto Dix, Stanley Spencer, Max Beckmann And Jacob Epstein (Edwin Mellen Press, 2005). I saw no hint in the curatorial texts of any reflection on such studies. Just as the exhibit shows little background context for Theo Jansen's work, there's next to no historical context provided for any of the artists beliefs, many of which have long precedents throughout the last centuries.

Meanwhile the various dual-sets of artists in The Believers, with their assumed personae and surgical transfigurations, are not at all original. They were trumped by Star Trek: The Next Generation, such as Episode 16 "11001001" (from 1987). The show introduced Bynars, who are a cyborg race of cute, lilac-colored space aliens who although pairs are linked as one functional unit. In fact Star Trek includes a much more wide-ranging play with individuality and identity: transporter accidents where separate characters merge into one new hybrid; the surgically-altered, evil Borg collective; artificially intelligent computers and robots who may or may not be alive, etc. Who's to say that the future won't bring cyborgs, clones, symbiotic pairs, split personalities, or self-designable surgeries? For the most part The Believers can't stand up to popular visual culture which is technically more complex, much more richly aesthetic, better to look at, and often a lot more fun.

And just what is at the edges of contemporary culture, pushing the boundaries and providing new information, knowledge, and wisdom? Modern medicine, evolution, biology, physics, chemistry – these are the newest alternatives to ancient make-believe and false beliefs. The sciences stretch the far limits of human knowledge and propel our vast imaginations. MRI scans and electron microscopes. That's what's radical today. The science's underlying explanatory basis – a philosophical naturalism – is far more productive than supernatural beliefs. It's what's radically extending belief, not just by storytelling but by revealing and modeling reality in all of its strangeness, pairing fantastic leaps of the imagination with reason not against it. In contrast, although it is at times silly fun, The Believers promotes irrational, anti-science, anti-thinking and ultimately irrelevant beliefs through an outdated tabloid-style approach to art, as if poorly crafted art could ennoble bland, decrepit supernaturalisms.