John Chamberlain Choices at the Guggenheim Museum

Crashed and Crushed as Art and Metaphor

By: Charles Giuliano - Apr 25, 2012

John Chamberlain: Choices continues through May 13 at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 1071 Fifth Avenue, at 89th Street.

During the late 1960s I knew the sculptor John Chamberlain (April 16, 1927 – December 21, 2011) through a circle of friends in the orbit of the Castelli Gallery and Warhol’s Factory.

A big, gruff guy he was at the time in a funk and on the outs with Leo and his gallery director Ivan Karp.

Like a moth to a flame he was both attracted to and scorched by proximity to his famous gallery mate Andy. He was dating Ultra Violet one of Warhol’s ersatz Super Stars.

It was a time of transition in his work. The signature sculptures assembled from polychromed crushed car parts, while celebrated, were dated signifiers of the past. Like the assemblages of another Castelli mate, Robert Rauschenberg, he enjoyed initial success by bridging the gap from the slashing style of abstract expressionism into the cool irony of Pop.

While a running mate of the New York avant-garde, by the late 1960s, Chamberlain was having trouble keeping pace. Ultimately, although he experimented within his mandate- the crush sensibility- he lacked the breadth of imagination, and inovation of his peers.

In the heat of the New York studio, stripped down to reveal the swallows on his pectorals and feet, a legacy of his stint in the Navy from 1943 to 1946, he mused about trying new things. He talked about using the air brushed lacquer of an auto body shop to make paintings.

I watched as he and assistants wrestled with large slabs of foam rubber. The material that was then widely used for cheap mattresses and upholstered furniture. He used rope to hold the forms together. Now and then into a cavity formed by a circle he stuffed in a block of foam. Kind of like the stem of an apple.

In their first incarnation, particularly watching their sumo-like fabrication, they seemed fresh, inventive and vital. It was compellingly typical of the artist that the work resulted from physically struggling with the material. Forcing and shaping it to serve his will and vision.

Making art as a contact sport.

Leo didn’t like them. It wasn’t so much a matter of taste. More importantly, one of the most entrepreneurial and brilliant gallerists of his generation, Castelli couldn’t sell them. Collectors balked, perhaps rightly so, that the material was not archival. As we all know those foam rubber mattresses disintegrated with time.

Seeing some examples of that work along the tortuous spiral of the Guggenheim Museum they now look more dingy than fresh. Experiments with industrial materials all come with caveats. Artists tend to ignore those limitations.

When, for example, the TV sets of Nam June Paik installations or the fluorescent tubes of Dan Flavin’s light sculptures are no longer manufactured. That serendipitous spontaneity of the moment causes future headaches for collectors and the conservators they employ.

The foam pieces were shown not by Castelli but by the Dwan Gallery which focused on artists of the minimalist movement. To which Chamberlain, at best, had a tenuous relationship.

On another day we drove a VW van to the studio of his friend Donald Judd and picked up a load of rejected galvanized boxes. Judd was notoriously exacting in specifications for fabrication. There were four of us and I tagged along at the invitation of my friend Jim Jacobs, now a private dealer, who worked for Castelli at the time.

Down town they were placed into and crushed by a bailing machine. No longer boxes the mangled objects were more difficult to fit into the van. Back in John’s studio he spot welded them to create new works.

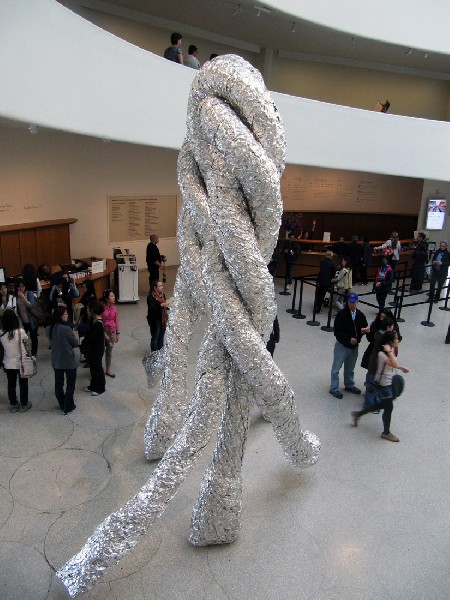

Encountering one of them at the Guggenheim it seemed anomalous compared to the more lively polychromed pieces that came before and after. It was a clever idea but again just an interlude. There were others. I find the melted plexi pieces engaging or the spray paintings. Frankly I don’t know what to make of the crumpled tinfoil pieces including the enormous one on the ground floor of the museum below its vaulting spiral atrium.

After that experimental phase, when I knew him in the 1960s, he returned to working with car parts by 1974. We intersected in the Berkshires for one of those Thanksgiving celebrations in the church of Ray and Alice Brock in Stockbridge. By then I was living in Boston and out of touch with the New York art world.

But what I heard about John through friends was often disturbing. He could be a bully and opportunist. There was an ongoing lawsuit about an alleged Warhol that Chamberlain sold for millions. After several years it was settled out of court and my friends, while satisfied, signed a non disclosure agreement.

So there was a blur of after images, anecdotes, personal insights and prejudices as I careened around that epic spiral. For most retrospectives it is an unforgiving space. Here it seemed to work as a brutal assault of the senses. The impulse was to barrel through it from top down like the car crash, multi vehicle highway pile up which was the artist’s most compellingly metaphor.

It is not work that requires thoughtful meditation. The pieces smash into us with the immediacy and ersatz violence that comprised their creation.

While by the late 1960s, during the artist’s creative menopause, the work looked dated. By now that hardly matters. There is a familiar cycle where initially a young artist is embraced as fresh and edgy, then lulls into complacent repetition often dismissed as outmoded. A handful of artists transition into rediscovery as having been paradigmatic of an era. Which one, by then, doesn’t really matter.

John was fortunate to have influential supporters. The Dia Foundation and his pal Judd, through whom, Chamberlain’s work is seen in stunning depth at the Chinati Foundation in Marfa, Texas. And now, the Guggenheim Museum has mounted a retrospective just a year after his death.

It is always interesting to see the early work of an artist and steps that lead to their signature style. He was working with metal in 1952 (then 25 years old) and welding by 1953. By 1957, while staying with the painter Larry Rivers in Southampton, New York, he began to include scrap metal from cars with his sculpture. From 1959, until his “hiatus” nearly a decade later, he enjoyed success for the crushed car sculptures.

The Guggenheim includes some early works that reveal his debt to David Smith. They are small, compact pieces that are remarkably fussy with a lot of visual elements and information. These early works require us to slow down and focus to absorb and unravel their complexities. While derivative they are engaging.

Of course one does not get anywhere imitating the better known work of others. Chamberlin was able to launch a career from welding metal like Smith and taking it to a new generation by incorporating the inherent colors of car shards. The resulting works were both seemingly random and amazingly prescient and deliberate. It begs the difference of regarding the artist as a savant who tripped over a great idea in a junk yard, or a singularly unique vision, an eccentric and aberration resisting the mainstreams of prevailing movements and styles.

Pehaps his enduring legacy is as a maverick, a square peg that fits no stylistic hole. A life and career based on zigging where others zagged. A kind of opportunist and gambler who had the great fortune of being able to extract just what he needed from the prevailing zeitgeist.

In the late period what had been serendipitous became more deliberate. He took to splashing on and spraying color, sanding it down and buffing to enhance that aspect of the work. To paint in metal. Or to use only one part of the car, like long thin bumpers. Becoming more concerned with the deliberate creation of forms and colors.

While looking the same as the early works the sculptures became larger with more deliberation and control. It is the familiar approach of wanting to bring new and mature approaches to a career long focus on a narrow aesthetic and self imposed set of rules.

During his late career wealth and success allowed for bigger studios resulting in larger works with expanded materials and techniques. One of these monumental late works is displayed outside the museum.

The shift is subtle and it is up to curators, critics and the art market to determine the monetary and aesthetic value of the late work. Will the most coveted pieces come before or after the hiatus period?

Ultimately, as we trotted through this exhibition there was that daunting question. Was this the work of a great artist? A giant of his generation? Or the rough and tumble oeuvre of a one trick pony?