Duncan Rock Rocks BLO's

Libertine Gets his Come-upance in Mozart Classic

By: David Bonetti - May 04, 2015

Don Giovanni

Music by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Libretto by Lorenzo da Ponte

First performed in Prague in 1787

Boston Lyric Opera

Shubert Theatre, Boston

May 1, 3, 6, 8 and 10, 2015

Conducted by David Angus, BLO music director

Staged by Emma Griffin

Sets designed by Laura Jellinek

Costumes designed by Tilly Grimes

Lighting designed by Mark Barton

Cast: Duncan Rock, baritone (Don Giovanni); Jennifer Johnson Cano, mezzo-soprano (Donna Elvira); Kevin Burdette, bass (Leporello); Meredith Hansen, soprano (Donna Anna); John Bellemer, tenor (Don Ottavio); Chelsea Basler, soprano (Zerlina); David Cushing, bass-baritone (Masetto); Steven Humes, bass (Commendatore)

For its last show of the season, the Boston Lyric Opera put on a light, audience-pleasing production of one of the most popular operas in the opera repertoire, Mozart’s “Don Giovanni,” which emphasized its comedic elements over its tragic dimension. Which might be exactly what Mozart intended – he called it a dramma giocoso, a comic opera, despite the murder that sets it in action, the numerous conquests of the title Don (today, we would call most of them rapes) and the ending in which he is pulled down into the fire of Hell for his sins.

Early and mid-20th century academics, who generally had little sympathy for opera, a mongrel art form, anointed “Don Giovanni” the greatest of the genre. So, students who took humanities courses, who had probably even less sympathy for the art, left college with that received idea. Tastes and aesthetic values change with the times, and I doubt you’d find many opera-lovers today – or even academics - who subscribe to that idea. Many wouldn’t even argue that “Don Giovanni” is Mozart’s greatest opera, nominating “Le Nozze di Figaro” or “Cosí fan tutte” instead. Both are seen as more modern, ending in reconciliation of the sinners with the sinned against rather than a punishment that seems a throwback to the middle ages. (Of course, none of the protagonists of those two works committed murder, and if they strayed from their betrothed, none could boast of 2,065 conquests, as Don Giovanni has listed in the little black book, overseen by his faithful servant, Leporello.)

So, perhaps it is better to pass over the moral ambiguities with a light hand, focus on the comedy and the glorious music, which is what the BLO did, entrusting the production to a new team that was debuting with the company.

And they put on an attractive, stylish production, post-modern without violating the basic text, that avoided the disastrous ideas with which certain directors who thought they were working in Stuttgart afflicted previous BLO productions - its “Magic Flute” and “Midsummer Night’s Dream” springing immediately to mind.

Of course, the new team, none of whom have starry resumés, took liberties with time and space that will have traditionalists up in arms. All the action takes place in the same set, which is supposed to be the Don’s palace, so the opening scene in which Donna Anna rushes from her palace into the public square after being accosted by the Don, seems to be occurring somewhere else in his palace. Was she a guest at his costume ball? No, she wasn’t, but if you don’t know the plot, you might think so. Similarly, the rustic wedding of Zerlina and Masetto, a pair of peasants, seems to be happening in the Don’s salon. Unlikely. And there is no cemetery for the cemetery scene, so the statue of the dead Commendatore doesn’t come to life – he seems to have been kept in cold storage in the Don’s back room. But by not having to change sets every 20-minutes of so, the action moves faster, nothing really important gets lost, and, not incidentally, the BLO saves money.

And then there were cuts. Was Don Ottavio’s “Il mio tesoro” cut, or was the tenor’s performance so weak that it passed by without my noticing? Ordinarily, it is one of the most popular arias in the work. I most heartily agree with the elimination of the epilogue, when after the Don’s descent into Hell, the cast returns to offer morals that have already been adequately displayed by the drama.

What I liked about the new production team, many of whom have worked together before, is that they created vivid stage pictures. That salon, by set designer Laura Jellinek, in which nearly everything takes place, is a handsome room, paneled in wood painted a light green, decorated with a painting by Egon Schiele, an extravagant chair Carlo Bugatti and a massive chandelier that might have come from the Dutch design collective Droog by way of the Wiener Werkstätte. (There was also a life-size snarling silver tiger, the source of which I can’t place.) That sets the scene in fin-de-siècle Vienna, but other elements, like the gowns of both Donna Anna and Donna Elvira, are of the period in which the opera was written and some seem contemporary as well, for instance, the Don’s blindingly white tank top and Zerlina’s dress, which she might have just bought at the new Zara in downtown Seville. In other words, everything is fluid - the setting, the costumes, the morals. And the final scene, in which the Don is consumed by Hell fire, which is almost always unconvincingly staged, was creatively rethought – Hell and its demons, dressed in black and wearing weird ram’s horns’ helmets, came to him instead.

Costume designer Tilly Grimes shared Jellinek’s stylish vision. Donna Elvira’s red gown is not only haute couture gorgeous but it serves as a correlative for her character – “a little bit slutty, a little bit nutty” (with full apologies for the victim that memorable term was originally aimed at). Donna Anna’s blue and white gown suggests her more chaste character, and if you have a hunk like Duncan Rock as your lead, how could you resist putting him in a tight white tank top? (For most of the opera, he wears a tuxedo, to equally sexy effect.) Grimes went all out for the masked partiers, creating for each one a highly individualized outfit and wig (thanks to BLO wig-designer Jason Allen). Most were brightly colored, so the stage picture popped like a Pop art painting.

Lighting designer Mark Barton was fearless using spots, most effectively one played on Donna Elvira, stage center, facing the audience, illuminating her and her red gown, as she sang her great second act aria “Mi tradi quell’alma ingrata” (The ungrateful man betrayed me/and caused me such misery, O God!) BTW, having a singer stand at stage center facing the audience has been considered uncreative and old-fashioned for at least 50 years, but I think it is a tradition that should be revived occasionally now that we’ve watched singers valiantly singing their big arias while being lowered onto the stage by a crane or under a heap of rags or other such nonsense – remember poor Nadine Sierra, who sang Gilda so beautifully in the BLO’s “Rigoletto” last year, being made to sing her big aria, “Caro nome,” flat on her back? By happy contrast, Donna Elvira’s big moment was chic, dramatic and beautifully sung by Jennifer Johnson Cano (more about that in a moment.)

And of course, stage director Emma Griffin, who seemed to have thought out the implication of every gesture and movement of the drama, pulled it all together. (She was helped in several cases, most obviously by Kevin Burdette’s Leporello, by singers who understood the acting traditions from which their roles were derived.)

Forgive me: I forgot to give a brief summary of the plot. I guess I assumed that everyone reading this had taken one of those introductory humanities courses back in the day, and already knew it.

The basic story is simple, archetypal even, if filled with complications. Don Giovanni is based on the legendary Don Juan. The Venetian Casanova would fulfill the type a hundred years later. A man more concerned with the number of his conquests than their quality, never mind the issue of love, he is the avatar of the amoral, rapacious man, initially charming, above all seductive, but reprehensible as his acts unfold. His faithful servant is Leporello, who does his best to clean up after his boss – and keep the running score of his conquests up to date.

There are two women, Donna Anna, whom the Don has just raped or tried to, whose father, the Commendatore (the Commander), he then kills when he comes to her defense; and Donna Elvira, with whom he spent three delirious nights and then dumped, who is looking for both revenge and reconciliation. (He must have been fantastic in bed.)

There is a subplot about the peasants Zerlina, whom, of course, the Don tries to seduce, and her stalwart betrothed, Masetto. Oh, and there is Don Ottavio, Donna Anna’s feckless fiancé.

Now, of course, you want to hear about the singers, which is why most people come to the opera in the first place. The reason I led with praise for the production team is that that is often BLO’s Achilles’ heel, at least in its main stage series. And, for once, the company seems to have gotten it right.

The cast included no big stars – not yet, at least – but at least two have that potential. Fortunately, they were both major roles.

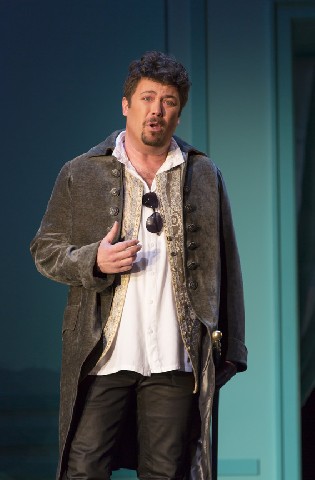

As the title character, Australian-born Duncan Rock, making his American debut, was a real dreamboat. A handsome red head, suave, tall and well put together, he really filled out that white tank top, but he looked even better in his tuxedo, the tie loosely hanging. He acted as if the role of the rake was a natural for him, which in real life might be a little troubling. Given his ease with his body, he gave a real physical performance. In the opening scene, he and Donna Anna have a believable tussle between a wronged woman and her seducer who is trying to escape and then he has a real fight with her father, who has come to her defense (although they don’t pull their swords, which is traditional). But he is more than just a brawler.

In the lovely second act serenade, “Deh, vieni alla finestra,” (Come to the window), addressed to Donna Elvira’s maid, whom he has marked as a potential new name in his book, Rock leaned casually against a pillar and sang as if he didn’t have a care in the world. Accompanied only by a mandolin, he sang with beguiling lyricism, even producing a nice little improvised ornamentation. Possessed of an attractive light baritone, Rock has sung at major houses in Berlin, London, Madrid and Paris. We are lucky to get the chance to hear him here at an early stage of his career. I suspect that Don Giovanni will be a role with which he will make his mark.

Don Giovanni is a narcissist driven to prove himself by his conquests, which can be interpreted in many ways. He is seldom portrayed purely as a rapist like Scarpia in “Tosca” – but really, there’s no other way you can present Scarpia. There is no ambiguity there. In a controversial performance I heard in San Francisco, Dimitri Hvorostovsky gave a cold, hard, unemotional performance of the Don that was chilling. Rock played the Don like a playboy who is having the time of his life, enjoying every minute of it, seeing the relentlessness of Donna Elvira as an inconvenience and his murder of the Commendatore as merely collateral damage. His is a totally amoral Don who enjoys life to its fullest and probably gives the women he seduces, whether willingly or forced, the time of their lives. He is totally unprepared for the tightening circle of those seeking revenge closing in on him.

The Don has met his match in Donna Elvira, who is torn between revenging his desertion and enticing him back into her bed. As Elvira, mezzo-soprano Jennifer Johnson Cano, who was making her BLO debut, gave a brilliant performance. Her voice was full through all her registers and she hit all her high notes without forcing. A good-looking woman, she was glamorous in her red dress, and she knew how to occupy a stage. Donna Elvira has been portrayed as a nutcase who runs onto the stage to interrupt whatever else is going on, but Cano saw her behavior as more rational and her seeking of revenge as justified. Although repeatedly drawn back to her seducer – and that remains a problem for many abused women today – she is focused on making him pay for his transgressions against her and other women. As portrayed by Cano, Elvira is a proto-feminist, and she triumphs in the end. A member of the Metropolitan Opera’s Lindemann Young Artist Development Program, Cano has sung a number of smaller mezzo roles at the Met. We’ll be hearing more from her in the future.

As Leporello, bass Kevin Burdette was a total delight. He gave an electrifying performance in 2011 in the BLO’s “The Emperor of Atlantis,” the one-act anti-war allegory composed at the Theresienstadt concentration camp that promptly got its composer and librettist (Viktor Ullmann and Peter Kien) sent off to Auschwitz and their deaths. Burdette might not have the most mellifluous voice, but, boy, does he know how to deliver opera buffa style recitative and acting. Every gesture, every pose, every utterance of his was on the mark. And his Italian enunciation was like that of a native. Burdette’s performance could prove a textbook illustration on how to make the arcane style, dating back to the commedia dell’arte, alive on today’s stages. If he were still alive, I’m sure Dario Fo would approve. And he was able to persuasively sing-talk his way through his great aria, “Madamina,” which catalogues the Don’s conquests to Donna Elvira: 640 in Italy, 231 in Germany, 100 in France, 91 in Turkey, but, he ends, in Spain, 1,003. In other words, calm down woman, you are not alone.

The weak center of the production vocally was the Donna Anna of soprano Meredith Hansen, an alumna of the BLO’s Emerging Artist Program. It’s nice to support your peeps, but Hansen was not ready for a role that often is more central to the drama than that of Donna Elvira. She gave it her all, but her voice was metallic in tone and her top notes were forced and shrill. As her fiancé, Don Ottavio, tenor John Bellemer made such a weak impression that I can’t remember him singing his most important aria. (If they cut “Il mio tesoro,” the BLO made a major mistake. If they entrusted it to Bellemer, and I can’t remember him singing it, they made an even more grievous mistake.)

As the Commendatore, bass Steven Humes, lacked the bone-chilling low notes that makes the small role so terrifying. He has sung the role in Paris, Madrid, at the Bolshoi and the Salzburg Festival, so what do I know. Other than that his singing left me cold.

As the peasant lovers, Zerlina and Masetto, Chelsea Basler and David Cushing, both members of or recent graduates of the BLO’s Emerging Artist Program, made a charming young couple; Basler, hipper and more worldly, Cushing, a country bumpkin willing to forgive his fiancée for being unfaithful with the Don. Cushing, a bass-baritone, proved as serviceable as always, but Basler was sadly off her game. She was outstanding in the BLO’s Yucatan-set production of “The Magic Flute” as Pagagena, and she was terrific in the lead role of the BLO’s annex production of Frank Martin’s “The Love Potion.” As Zerlina, a role one would have thought to suit her, her voice was thin and weak and often irritatingly nasal. Young artists have to learn which roles are right for them. I heard Renée Fleming, already in her prime, give a disastrous performance of the title role in Charpentier’s “Louise” at the San Francisco Opera. I don’t think she’s sung it since.

I wish I could praise David Angus’s conducting of the BLO orchestra, but once again, due to the weird acoustics of the Shubert, much of it was inaudible – for instance, I saw three trombonists emerge for the final scene when the Don is consigned to Hell, but even though I focused on them, I couldn’t hear a note they produced – and the rest was imbalanced. In the overture, the brass, which sounded like something from a small town concert band, overwhelmed everything else.

But those caveats aside, granted some of them significant, it was a pleasant evening at the opera.

POSTSCRIPT: the BLO has good news to report. The Calderwood Charitable Foundation, which has enriched so many local cultural organizations, has give it a $5 million grant, the largest single gift in its history, to endow the position of the General and Artistic Director, currently held by Esther Nelson.