Flush With The Walls at the Museum of Fine Arts

1971 Men's Room Show Pissed Off the MFA

By: Sarah Hwang - May 07, 2011

Under the Museum of Fine Arts director, Perry T. Rathbone, there was a beginning of interest in European modernism, primarily German Expressionism. Rathbone had befriended Max Beckmann when they both resided in Saint Louis. With the curator of decorative arts and sculpture, Hanns Swarzenski, Rathbone bought the late painting “Rape of the Sabines” during a visit to the studio of Picasso. As a matter of policy, however, Rathbone and the MFA had no interest in contemporary art or Boston’s community of artists.

As a result, a group of Boston artists, led by the Smart Duckys, protested silently and creatively, staging a guerilla exhibition called Flush with the Walls within the Museum’s imposing marble Men’s Room on June 15, 1971. After the breach of the MFA’s security, and protests from the Boston Visual Artists Union, Rathbone announced the appointment of Kenworth Moffett as the museum's first Curator of Contemporary Art.

To this day, Boston still struggles with contemporary art, but the events of the 1960s and ‘70s proved to be a turning point. The Institute of Contemporary Art now resides in an award winning building by Diller Scofidio + Renfro. The MFA recently opened its new Art of the Americas wing, designed by Lord Norman Foster. Because of the city’s current attitude of progress and change, it is important to remember the events and individuals that revolutionized Boston’s attitude toward contemporary art some 40 years ago.

The 1960s was a time of turmoil for the struggling Boston art scene. The success of the Boston Arts Festival from the previous decade, an annual outdoor event that included a juried art exhibition, became a thing of the past. The ICA, which sponsored the Festival and was once a leader of contemporary art, lost its lease on Newbury Street had to relocate back to an earlier, abandoned building on Soldier’s Field Road in Brighton. The makeshift structure had been created after several moves to different locations by founding director, James Plout.

Under ICA director Sue Thurman it presented ambitious shows, including Warhol’s first museum level exhibition, an installation of “Barney’s Beanery” by Edward Kienholsz, and the American selection of the Montreal World’s Fair, in Horticulture Hall. By the end of the 1960s the ICA was insolvent and without leadership. It would be be ressurected by Andrew C. Hyde with strong support from Boston's then new mayor Kevin White. The deputy mayor, Kathy Kane, and her husband, Louis Kane, would emerge as trustees of the struggling ICA.

The Newbury Street galleries were not motivated to show contemporary Boston artists. The spaces were small and expensive. The art world was changing especially when it came to the scale of art. As Clement Greenberg declared Abstract Expressionism signaled the end of easel painting; what was a celebrated Academic art tradition he regarded as kitsch. The Newbury galleries could not accommodate these “non-easel” works and the MFA was not interested in investing in them.

The bigger obstacle that artists faced was Boston’s conservative taste. The MFA was (and is) the single representative of Boston’s cultural taste and it, too, was old-fashioned. The MFA has world class collections of Ancient Egyptian, Classical Greek and Roman, Asiatic, European Painting and Decorative Arts, prints and drawings. The great collection of American Art started in the Colonial era but faded by the 1930s. There was no photography other than a donation of works by Alfred Stieglitz at that time “lost” in the basement.

Rathbone, the MFA’s Director from 1955-1972, somewhat transformed the museum’s program. He implemented the first exhibition of modern art in 1957 European Masters of Our Time and continued to exhibit modernists, such as Paul Klee, Arthur Dove, Max Beckmann, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Vincent vanGogh, and Amedeo Modigliani. The MFA exhibited Boston artists, such as John Singleton Copley, Washington Allston, and even the Boston Expressionist Hyman Bloom.

Arguably, Rathbone was aware of the Museum’s nature and wanted to introduce it to the 20th century. In a 1956 report, he proposed a collaboration between the MFA and ICA:

The need of the Institute of Contemporary Art to find new and more adequate quarters and the desire of both the Museum and the Institute to interrelate their programs and to develop a working arrangement of mutual benefit led to making space provision for the Institute in the building of the Museum School, which was ready in September.

It seemed like the perfect arrangement: The ICA would have access to exhibition space and the MFA’s collection and the MFA would finally have a hand in the jar of contemporary art. It remains evident that Rathbone’s idea never moved past conjecture as no real collaboration was ever made between the two institutions.

Actually there had been had been an earlier attempt to merge the ICA with the MFA as its department of contemporary art. Under its then director, Thomas Messer, the ICA abandoned its seldom visited building on Soldier’s Field Road and moved into the second floor of the Museum School next to the MFA. For a time Messer “advised” the MFA on acquisitions including a major painting by the figurative expressionist David Park.

When Rathbone arrived at the MFA in 1955 he had his own ideas about modernism. Messer departed to become director of the Solomon R. Guggeheim Museum predating its tenure on Fifth Avenue in the Frank Lloyd Wright building.

The only place one could see local contemporary art during the late 1960s was Gallery 11 at Tufts University. Artists from an ICA show Boston Now at the gallery of the newly built City Hall were shown at Gallery 11 which led to the beginnings of the Studio Coalition. The Studio Coalition was an open studios event in the late ‘60s, America's first, that brought visibility to the artists’ work without the assistance of galleries.

Michael Phillips, a faculty member at Tufts University and one of the organizers of the event, believed that the artist did not need a gallery to show the work. As a result ten Boston artists gave studio exhibits which turned out to be a great success.

Building on that success, John Chandler organized an exhiition Three If by Air, with work by Katherine Porter, Andrew Tavarelli and Anthony Thompson, for the Obelisk Gallery on Newbury Street. Porter was selected for the Whitney Annual as was Tavarelli several years later.

In 1970, the Boston Visual Artists Union was formed. The BVAU was an organization that spoke for artists and the art community. They were a force for artist’s rights, contemporary art in the region’s museums, and political activism. Even its organizational structure represented this interesting combination, described in Daniel Ranalli’s Forum column in Art New England: “it was one part 1960s collective, one part United Nations, and one part co-op gallery”.

Meetings were held at Parker Street 470 Gallery across from the MFA. Parker Street 470 was a joint enterprise between four female gallery owners: Barbara Krakow, Portia Harcus, Phyllis Rosen, and Joan Sonnabend. The gallery was a two-story, loft space that was larger than the traditional gallery.

Charles Giuliano covered the first Studio Coalition event and was committed to the emerging scene of Boston artists. He wrote an article in his weekly ArtBag column in Boston After Dark challenging Boston artists “to do something for yourself” in order to gain exposure.

He and the writer/ curator, John Chandler, suggested to the founders of the Parker Street 470 gallery that the space should also be used for panel discussions inviting members of the art community to speak about contemporary issues. Eventually, this led to the formation of the BVAU. One of their first acts was to invite Rathbone to speak around the same time the MFA was holding their last centennial exhibition, Earth, Air, Fire, Water: Elements of Art.

Approximately 300 people attended and because of the pressure Rathbone was already under from the art community and the previous year’s acquisition of an illegally smuggled Raphael painting “Portrait of Eleanora Gonzaga” he seemed intimidated. Joan Trachtman, wife of Arnold Trachtman who was elected as the BVAU’s first Program Chairman, bluntly asked Rathbone when the MFA was going to show contemporary art. According to Giuliano, who attended the event, Rathbone avoided the question but “squirmed in his seat.”

Elements was the last of a series of exhibitions in 1971 celebrating the MFA’s 100th anniversary. This particular show consisted of an eccentric array of contemporary works; there were live eels swimming in water tracks, blocks of ice floating on the Charles River, and fire burning outside the MFA’s entrance. Though Rathbone had the right idea to organize a contemporary art exhibition Elements was conceptually disorganized. In a New York Times review, Hilton Kramer wrote:

What, you may well ask, do these disparate conceptions have in common other than their use of the four classical “elements”? I am not at all sure.

Their break with the traditional materials of the fine arts is more or less complete. Both nature and technology are employed in unfamiliar combinations. Yet there remains in much of this work a surprising reliance on esthetic “effects” of a rather old-fashioned kind. The means of achieving these effects are certainly new, but the effects themselves fit easily enough into one’s customary esthetic expectations.

What are more interesting are the divisions one discerns among the artists themselves. Some clearly aspire to make of art a phenomenon indistinguishable from natural process, whereas others seem determined to set up as rivals of nature bending the “elements” to their esthetic will with a little help from technology and the new synthetic materials. It would be a mistake, in any case, to think that the artists represented in the “Elements” show were agreed on some fundamental esthetic ideology.

The public, on the other hand, was in awe of the large-scale and unconventional art. 73,000 people attended the show, the highest record of attendance for any of the centennial exhibitions.

Still, many artists were unsatisfied. The MFA still did not have a department dedicated to contemporary art. In Rathbone’s 1970-71 annual report, he stated that the proposal for a Department of Contemporary Art was first recommended in 1967 but postponed for financial reasons. However, these tribulations did not stop the departments to acquire pieces for their collections that same year. Rathbone wrote again about the status of the potential department in his 1969-70 annual report: We have yet to appoint a Coordinator of Modern Art, although the position has been established by the trustees...

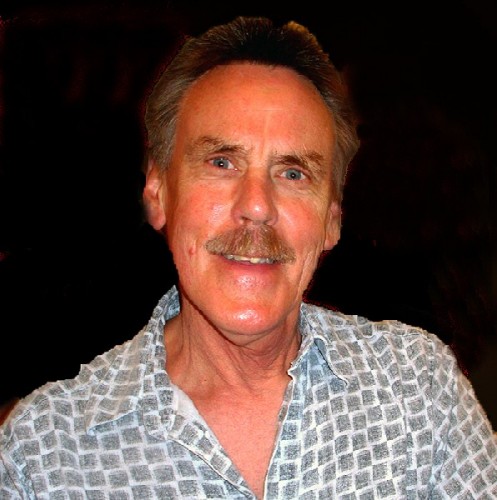

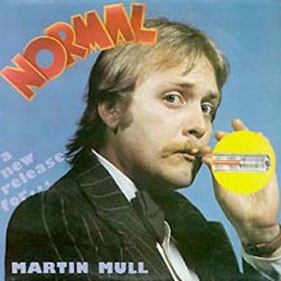

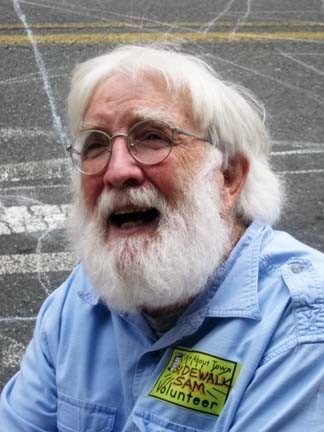

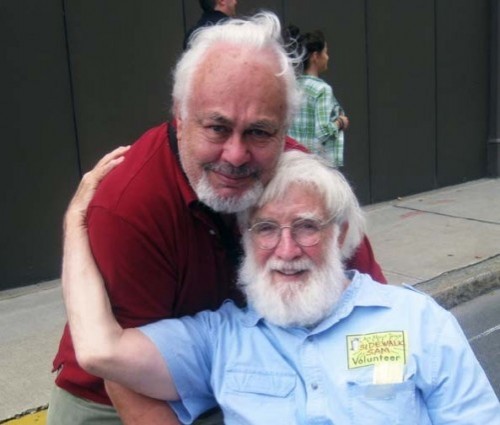

Two months after the opening of Elements, a group of young contemporary artists began to plan the guerilla exhibition at the MFA. Todd McKie, who was well aware of the MFA’s conservative taste and the lack of opportunities to show art in galleries, came up with the idea to have an impromptu show in the men’s room. Together with his peers, Martin Mull, Robert Guillemin (Sidewalk Sam), Kristin Johnson, David Raymond, and Jo Sandman, they began preparations for the show.

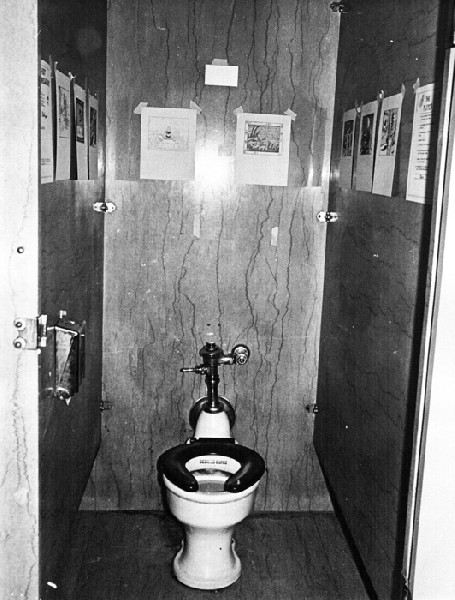

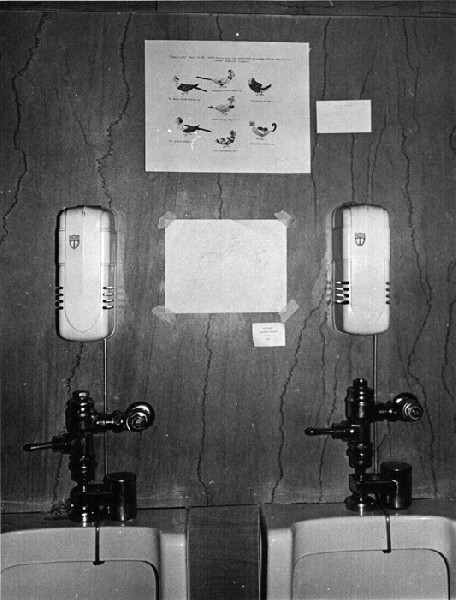

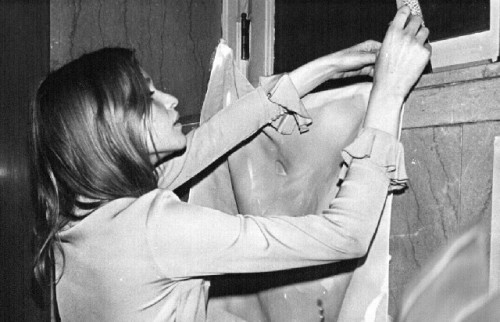

The artists created small-scale works, mostly on paper, so that they could be easily transported under their coats into the museum and hung on the bathroom walls. These consisted of David Raymond’s 13-month calendar of ticket tape, Robert Guillemin’s hanging of scrolls of string and paper, Kristin Johnson’s parakeet drawings , Todd McKie’s humorous drawings of primitive-inspired figures , Martin Mull’s cartoon series Chief Flying Breakfast and Jo Sandman’s bromide installations . Invitations were cleverly printed on toilet paper with the show’s title, Flush with the Walls, and sent to friends, family, and members of the art community. Even reporters and television crews were invited. On the invites, the guests were asked to keep the event a surprise and arrive promptly at 8pm.

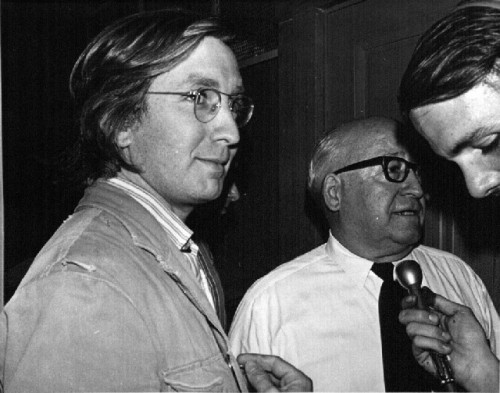

The show was a brief success until the guards noticed the large crowd of male and female spectators in the men’s bathroom. Guests arrived on time and no one, not even the reporters, leaked the event to the institution. Visitors who were there for the Cezanne exhibition became curious of the hullabaloo and partook in the event. Even Museum officials, William Lilly from the Education Department and President George Seybolt, visited the men’s room without any prior concern about the exhibition’s unofficial nature. However, one official did get involved with the event leading to controversy.

Diggory Venn, Administrative Assistant to the Director, was interviewed about the event for Boston’s WBZ station and suggested that the show be kept up for a week and even create a similar exhibition in the Ladies’ Room. This news obviously brought joy to the artists as this meant that the Museum was not only complying with the nature of the exhibition but they were finally going to show contemporary art created by Boston artists. Unfortunately the next day, the artists were informed that the entire show was taken down and the works were thrown out. Some of the artists did not care whether the works survived because the show itself was such a success. While others wanted to retrieve their art and met with the Museum to negotiate those terms.

Flush with the Walls was the final shove that the MFA needed in order for them to realize the importance of exhibiting living art. An article in Boston After Dark summarizes poignantly the activist success of the show:

This show besides an obvious challenge to the sacred cows of art and decorum brings several situations into sharp relief. The first is to point out that the men’s room seems to be the only place in the Museum of Fine Arts that an exhibit by contemporary local artists can be seen. Another is that protest does not have to be strident or destructive but can be creative and low key in demonstrating the obvious with wit and ingenuity. The irony of the situation was evident when one artist turned to another and said, “Congratulations on your first museum show.

Most importantly, the fun and spontaneous nature of the show was never compromised. Several articles wrote about the event’s “dada-ist” and “Duchampian” character. Todd McKie and Martin Mull were the witty members of the performance art group, Smart Duckys. One of their performance pieces was a traveling show where McKie and Mull created hors d'oeuvre sculptures of famous modernist works and served them to their audience dressed as waiters . However, to say that Flush With The Walls was the first time the artists expressed their feelings about Rathbone’s leadership is not accurate. McKie had a show at the ICA where he created artifacts, letters and hospital records, relating to a [made-up] incident involving the artist biting Rathbone on the nose.

Two weeks later, after the excitement of the BVAU discussion and Flush with the Walls was still fresh in everyone’s memories, Rathbone personally called Giuliano, then on the staff of the Boston Herald Traveler, and told him that he hired the first Contemporary Art Curator, Kenworth Moffett.

It seemed like a victory for the BVAU, but there would be challenges for the Contemporary Art Department. Moffett was a formalist who mostly acquired Color Field paintings for the Museum. At this time, Greenberg formalism was waning with the emergence and dominance of Pop Art, Minimalism and Conceptual art. Beyond Moffett’s personal taste, lack of funding may have also been a factor as to why he did not purchase other contemporary works.

The separate departments of the MFA, until the mantra of “One museum” during current director, Malcolm Rogers, operated as fiefdoms. The departments had individual endowments beyond the museum’s general acquisition funds.

The Asiatic Department is the most richly endowed and was at the time the most powerful in the caucus of curators. The Contemporary Art Department by contrast was relatively weak and unendowed. Giuliano comments, “Ken was Cinderella; he had no money, credibility, or status.” McKie also commented on the department, of course, with a sense of humor: “As far as the development of the MFA’s Contemporary Art Department, it ebbs and flows. Like every other artist, I wish they’d smarten up and buy tons of my work. That’s a joke. Well, not totally.”

When McKie commented on the effects of the Men’s Room show, he mentioned that he did not have political aims. He was sure of one thing: “It definitely caused the Museum to change their security arrangement.” And it is true; the guards retired their dog whistles and the MFA added an extra $56,000 to their security budget. McKie seems to be being modest (or witty) about the guerilla show, but the MFA has changed. Without the Men’s Room show and the BVAU, the MFA would have started collecting contemporary art much later. Still, the fight for contemporary art in Boston continues. Fortunately, it seems that the MFA has not forgotten the show’s aftermath: the old Men’s Room was transformed into the Department of Protective Services.

Editor’s Note

Sarah Hwang has adapted this article from a term paper she submitted for a seminar on Contemporary Boston Art at Boston University with Professor Theodore E. Stebbins, Jr. She wishes to acknowledge Many thanks to Todd McKie for all his help and especially, trusting me with his fantastic photographs; Ted Stebbins, Jr. for showing me where the old men's room was; and Charles Giuliano for his endless knowledge and giving me this opportunity.

Bibliography

1969-70 Museum Fine Arts Annual Report. Boston: MFA, 1970.

1970-71 Museum Fine Arts Annual Report. Boston: MFA, 1971.

1971-72 Museum Fine Arts Annual Report. Boston: MFA, 1972.

Bergantini Grillo, Jean. “Art: Project Inc. /Union of Artists.” Cambridge Phoenix. June 15, 1971.

Bergantini Grillo, Jean. “Men’s Room at M.F.A.” Cambridge Phoenix. June 22, 1971.

“Boston Museum Appoints Contemporary Arts Curator.” New York Times. June 4, 1971.

Faxon, Alicia. “Into the johns…& up the sculpture.” Boston After Dark. June 22, 1971.

Giuliano, Charles. “Artweek.” Art New England. October 1 1980.

Giuliano, Charles. Interview by Sarah Hwang. Phone Interview. Boston, MA. April 19, 2011.

Greenberg, Clement. “Avant-Garde and Kitsch” in Clement Greenberg: The Collected Essays and Criticism, ed. John O’Brian. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988.

Gunter, Virginia. Earth, Air, Fire, Water: Elements of Art. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 1971.

Kramer, Hilton. “Boston Museum Mounts an Unusual New Art Show.” New York Times. February 4, 1971.

Loercher, Diana. “Artists’ protest at MFA.” The Christian Science Monitor. June 17, 1971.

McKie, Todd. Interview by Sarah Hwang. Boston, MA. April 11, 2011.

Melton, Maureen. Invitation to Art; A History of the Museum of Fine Arts Boston. Boston: Museum Fine Arts Publications, 2009.

Ranalli, Daniel. “Forum.” Art New England. February 4, 1990.

Rosenfield Lafo, Rachel, Nicholas Capasso, and Jennifer Uhrhane, eds. Painting in Boston, 1950-2000. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2002.

Swarzenski, Hanns. The Rathbone Years: Masterpieces acquired for the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 1955-1972 and for the St. Louis Art Museum, 1940-1955. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 1972.

Whitehall, Walter Muir. Museum of Fine Arts Boston: A Centennial History. Cambridge: Belknap Press, 1970.