Laos

Part One: Luang Prabang

By: Zeren Earls - May 13, 2010

After an enjoyable week in Myanmar, we returned to Bangkok and connected with the other nine people in our group to begin the main trip; our first destination was Laos. Our flight out of Bangkok was delayed by two hours, while we waited for the smoke from burning fields to clear in Luang Prabang. As we had experienced a similar delay in Myanmar, it became clear that burning farmland before the monsoon season was a routine practice in the region.

The entire city of Luang Prabang, the former royal capital of Laos, has been designated as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO, which has also described it as “the best preserved city in Southeast Asia.” It is located on a peninsula at the confluence of the Mekong and Khan Rivers, with lush green mountains all around. To reach the old town, we transferred from the bus to tuk–tuks, which can negotiate the narrow roads in the heart of the city to the Maison Dala Bua, our hotel for two nights on the Mekong River. Befitting its name, which means “Princess of Lotus,” the classical oriental-style fifteen-room hotel has a lotus pond with ducks and is set amidst tropical gardens, offering a sharp contrast to the tumult we had just left behind in Bangkok.

Our afternoon tour of Luang Prabang took us through narrow lanes by aging 19th-century French colonial villas mixed in with worn Lao-style timber houses and temples. Time seemed to have stopped in the city, due to its isolation under Communist control. Luang Prabang was established six centuries before the Communists abolished the monarchy in 1975, imprisoning the royal family in a remote reeducation camp and setting up their own government in what had long been the capital city.

The Royal Palace Museum offered an insight into the history of the region. The palace was constructed by the French from 1904 to 1909 as a residential gift to King Sisavang Vong, as Laos had been part of French Indochina since the late 19th century. Cruciform in layout and mounted on a multitier platform, the structure exhibits a mixture of classical Lao and French beaux-arts styles. The ground floor has several halls displaying diplomatic gifts to the Lao kings, a collection of regalia, many gilded Buddha statues, and artistic treasures. The prize piece in the museum is the famed gold Khmer Pha Bang Buddha, which lends the city its name.

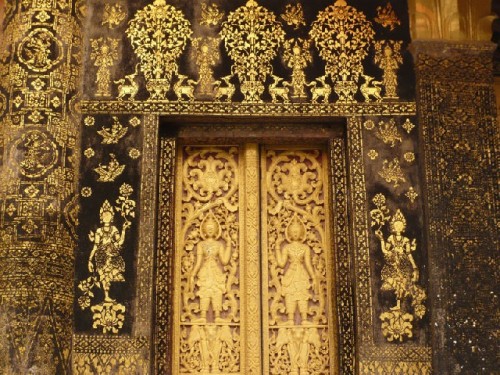

The royal temple or Wat Xieng Thong (Golden City Monastery), built in 1513, is the oldest in the city and was patronized by the monarchy until 1975. It has low sweeping roofs in the classical Luang Prabang style of temple architecture. Its eight thick supporting pillars, richly stenciled in gold, guide the eye to golden Buddha images in the back. Outside the rear part of the temple is an elaborate mosaic of the Tree of Life set against a deep red background. The combination of gold and deep red gives this temple a regal aura.

In the center of the old town rises Mount Phu Si, a nearly sheer rock with steep wooded slopes. We climbed 328 winding steps to the 79-foot-high summit, location of the That Chom Si shrine, which has an impressive gilded stupa in classical Lao form. The summit also offers views of the surrounding mountains, the city, and the rivers below. Finding a spot among tourists sprawled along the stepped walls of the shrine, we were rewarded for our climb by a sunset.

The next day we woke to the crowing of roosters and left the hotel at 6 am to participate in the ancient Buddhist ritual of giving alms to the monks. We took our place next to locals sitting on straw mats with food offerings on the sidewalk of one of the city streets. We shaped sticky rice into balls, which we kept warm in individual bamboo baskets. Hundreds of orange-robed monks from the nearby temples paraded before us in single file, the oldest at the head and the youngest at the end, to receive our offering in return for their prayers. This sense of calm and solemnity introduced by the monks continued in the temples we visited during the day. Despite the efforts of the Communist government to wipe out religion from Laotian life, faith remains a dominant force as children grow up giving alms, going to temples, and sustaining all Buddhist traditions.

On the way back we walked through the amazing blend of sights and smells at the morning market: customers were beckoned by a variety of meat smoking over charcoal fires, eggs boiling in cauldrons, insects sizzling in frying pans, and heaps of ants’ eggs mixed with rice. Spring rolls wrapped in freshly made rice paper and food to go packaged in banana leaves were popular choices for those on their way to work.

Returning to the hotel for a less exotic breakfast, we enjoyed a fresh fruit platter of watermelon, papaya, mango, and banana, along with warm French baguettes, butter, jam, and eggs cooked to order. Despite the smoky skies and smells wafting from burning fields, the languid pace of our setting provided a fluent sense of calm, which continued during our cruise on the Mekong River.

The Mekong, whose name means “the mother of all rivers,” is the world’s tenth longest river. It begins in Tibet and goes through China, Myanmar, Laos, Thailand, Vietnam, and Cambodia. It supports 90 million people, who produce 54,000 square miles of rice every year. Home to many species of giant fish, the river is the inspiration behind the phaya naga or Mekong dragons, which guard palaces and grace rooflines.

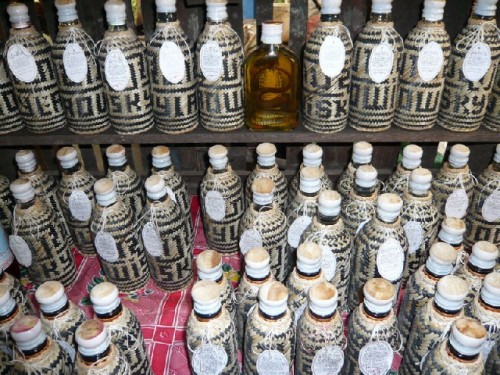

To reach the dock for our cruise, we walked through Ban Xang Hai (Jar-Maker Village), named after the village’s former main industry. Jars still abound, but they are made elsewhere. The village now devotes itself to silk weaving and to producing lao-lao, a local moonshine rice wine. Women at traditional looms wove silk fabrics displayed at stalls lining both sides of the road, while little children played underfoot or nearby. Though buying a silk shawl and a tribal silver necklace was irresistible, I kept my distance from the rice drink in bottles, some with a snake curled up in them as an elixir. I watched men boil and pack rice in earthenware jars to ferment for a week. The liquid is then drained and bottled. This rice wine has an alcohol content of 15%.

A two-hour boat excursion up river took us to the Pak Ou Caves, set in the side of a limestone cliff near the confluence of the Mekong and Nam Ou Rivers. Discovered in the 16th century, these two caves have been venerated ever since. They are filled with Buddha statues of all sorts and sizes, placed onto rock shelves and crammed into crevices by the faithful as offerings to the river spirits to ensure a safe journey, in a melding of superstition and faith. The lower of the two caves is easily accessible from the river, though we had to jump from boat to boat five times to step ashore. The upper cave may be reached by steep steps cut into cliffs and is deeper, requiring a flashlight for exploration. High above the water by the mouth of the cave are marks indicating water levels from monsoons in different years. A sheltered area between the two caves provides a pleasant spot for a picnic lunch.

Lunch for us was on the boat, prepared by the crew. Over lunch we continued our learning and discovery. Ole, our Laotian guide, explained that the government had controlled all land and business and discouraged the practice of any religion during the first ten years after the Communist takeover in 1975. Later on land was given back to people and private ownership was allowed. A majority of people are practicing Buddhists; Christianity and other religions are tolerated as long as there is no proselytizing.

Education is free at all levels; parents pay for books and uniforms. Poor farming families turn to monasteries to benefit from free education and to protect their children from becoming involved in the lucrative drug trade. Children cut off all ties with parents when they attend school to be monks. Until the age of twenty they are novices and wear robes covering only one shoulder. When they are eligible to become monks, they commit to the various stages of monkhood and do not leave the monastery unless they want to renounce monastic life. Regular schools are in session from September through May; students are on vacation for three months during the monsoon season.

Idling past the stalls of the Night Market offered a feast for the eye. People from Hmong tribes trek down the mountains to sell their hand-loomed indigos and sophisticated patchwork, along with other special crafts, at this market. Treasures I picked up here were bags of various sizes with hand-embroidered motifs, a cushion cover with a reverse appliqué pattern, and a multicolor patchwork quilt. All my purchases were made with US dollars, accepted throughout Laos.

Dinner on our final night in Luang Prabang was at the Boulevard Restaurant near the Night Market. Cucumber soup with pork preceded a spread of sweet-and-sour pork, chicken with cashews, vegetables, rice, and morning-glory salad, all followed by a fruit plate of sliced mango, dragon fruit, and watermelon.

The calm and peaceful animation of this royal city and monastic center, refined across centuries, prepared us well for our lengthy journey by bus to Vang Vieng the following day.