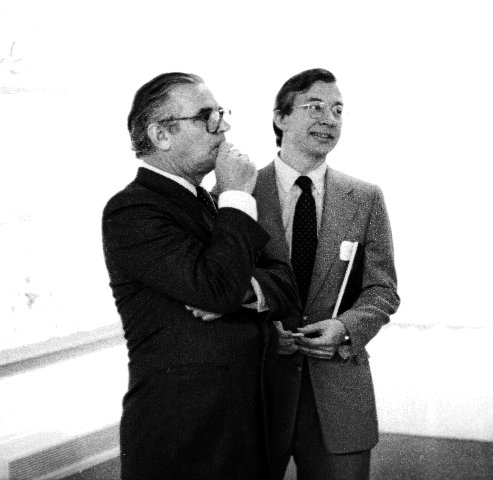

How Jan Fontein Stabilized the MFA

From Curator of Asiatic Art to Director in 1975

By: Charles Giuliano - May 17, 2020

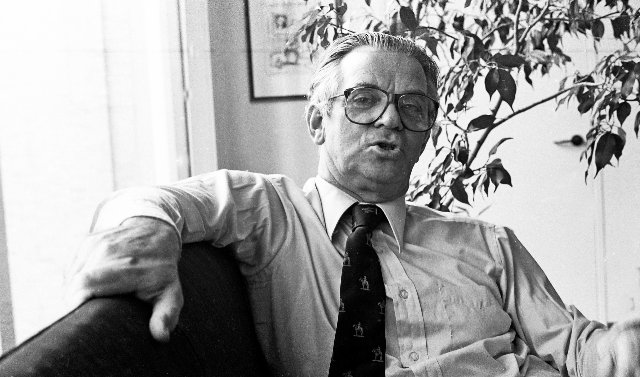

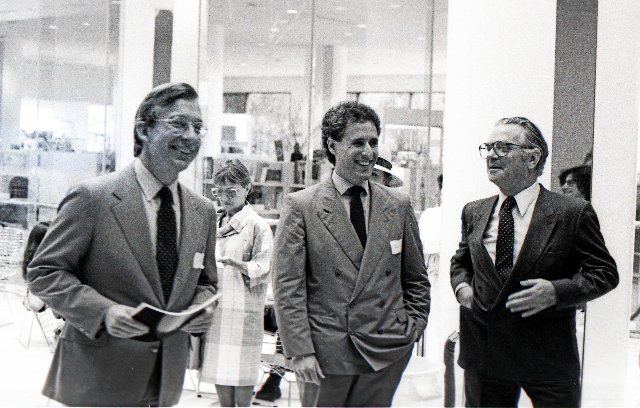

The Asiatic collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston is regarded as the world’s most comprehensive. The Dutch born, Jan Fontein (1927-2017), joined the MFA in 1966 as its curator.

During a period of turmoil, and a musical chair of leadership, he was made acting director in 1975 and soon that became a permanent position which he held until 1987. The accomplishments of his tenure are many. He brought administrative stability particularly to the fiefdoms of competing department heads. It was essentially a curatorial coup that had ousted his predecessor Merrill Rueppel.

From the first days of his administration, which coincided with the appointment of MIT president Howard Johnson to chair the board of trustees, together they established priorities.

These included vital climate control renovation and reinstallation of the Asiatic Wing and the Evans Wing of Painting. The museum was reoriented through the design of I.M. Pei’s multi-purpose West Wing.

As a self-defined populist, he was down to earth and accessible. He deftly fielded difficult questions and appeared to enjoy the give and take of interviews. I spoke with him quite often at press events as well as privately. This interview occurred in April, 1983. There is also a March, 1984 transcript that will be posted.

Charles Giuliano The last time we spoke was just before climate control renovations were announced.

Jan Fontein I didn’t realize it had been that long. I’ve been doing this now (been director) and there were several things which we set out to do. Much has been done with much yet to do. It’s always good to look back after several years. What haven’t we yet done and what could have been done differently. That’s a useful exercise for me and the trustees.

You have been around this museum since you worked here in the Egyptian Department. (1963-1966) I don’t have to remind you that the museum has changed. You know that so it makes it easier for us to talk about that.

My appointment as director of the museum, and that of Howard Johnson (president of MIT) as president of the museum, practically coincided. He came on in September and I was appointed as actual director having served as acting director. In 1975 I became acting director and director in 1976. At that time, we discussed what we wanted to achieve. One thing was climate control. That’s not finished but very soon we will resume that process with the Evans Wing (of Painting). We have finished projects and want to pause and see what we have done.

In the past year the country was in such an economic state that the museum had to be prudent. Policy required that we look and see before moving full steam ahead during a time of recession. I am sure that within a reasonably short period of time we will go full ahead with the Evans Wing. Once we start it will be a year and a half until it is finished. It’s much less complicated than new construction or rebuilding the Asiatic collection.

The Asiatic collection entails an enormous diversity of objects: Pots, paintings, textiles, screens and scrolls. Compared to which, with the Evans Wing you are looking for clean galleries with open walls. You then hang pictures and it’s a much less complicated operation.

The Evans Wing, which was constructed several years after the initial museum, (designed by Guy Lowell) is slightly different. There is sufficient space behind the walls for the necessary duct work. When we initially talked, we were not discussing a new building. (Wing designed by I.M. Pei) There had been a previous trustee decision not to go beyond the perimeter of the existing building. Later, very wisely, the trustees decided to abandon that decision. I.M. Pei then polled all of our hopes, ambitions and requirements.

CG When did Pei become involved?

JF I remember very well standing on the top floor in the library on the other side. There were windows which are still there. They now look down on the glass dome of the galleria. I looked outside and recognized Pei. I had met him a number of times. He was circling the building with a notebook in hand. He came up with the idea of a new wing and everything that’s in it.

CG Which makes perfect sense.

JF Of course but it’s his job to draw up the plans. Our job is to list our needs. We have now been using the building which has not yet performed all of its functions, as a loop connector. That will not occur until the Evans Wing is renovated. In every other sense the building has been everything we hoped for.

(The design of Pei changed the main entrance away from Huntington Avenue and its grand staircase flanked at the top by special exhibition galleries. The Fenway entrance was downgraded. The Lowell plan did not allow for easy and logical access to permanent collection galleries. Entering from the side, in the Pei building, allows for loops on two floors. The Pei building also provided amenities such as dining, book store, auditorium, and special exhibition galleries. That space is now assigned to modern and contemporary art. The former Gund special exhibition gallery is now in the basement of the wing designed by Lord Norman Foster. During his brief tenure the director, Merrill Reuppel, suggested the removal of then largely decorative and space consuming grand staircase. There was broad opposition to that suggestion.)

CG What was the cost of the West Wing?

JF It’s difficult to say exactly. There are many ways of looking at the total cost. The primary cost has been climate control. The plant for that is below the West Wing and was some $10 million. That’s about a third to half of the construction cost. The entire cost is difficult to calculate. It’s the same with (renovation of) the Asiatic Wing. How much of the total cost of the project do you assign to climate control? You can kind of calculate on a square foot cost basis.

CG How much did you have to raise and how much of that came from the National Endowments?

JF The total money raised is $25 million and of that the Endowments gave $2 million. That was a challenge grant for climate control. We had another grant for installing the education department in the West Wing (basement area near the cafeteria).

CG Compared to $25 million overall the NEA money of $2 million seems relatively small.

JF We got the Endowments money at a time when the credibility of the museum was low. We had never undertaken a large project like this. As you know, the museum was in a lot of trouble. There are institutions that go through this during the duration of an institution over a long period of time.

(The museum had to return to Italy an alleged Raphael portrait of Eleonora Gonzaga. It was smuggled into the U.S. by MFA curator Hans Swarzenski in an arrangement imitated by MFA director Perry T. Rathbone. It was intended as a centennial coup in 1970. Rathbone was forced out by board president George Seybolt. On his own initiative Seybolt hired the relatively unknown Rueppel. It was not a good hire and a cabal of curators forced his termination. Classical curator, Cornelius Vermeule, became acting director and allegedly aspired to a permanent appointment. Reuppel was chosen over him. Then Fontein became acting director. These events and transitions negatively impacted the status of the MFA as referenced here by Fontein.)

JF At that time, we were regarded as a museum that had been in a lot of trouble.

CG When you came to the museum (from Holland as head of the Asiatic Department) did you ever imagine becoming director?

JF If I was told that years ago, I never would have believed it. I can tell you a few things because most of those problems are now far behind us. In a short period of time we had seen one director go. A short time with an acting director (Vermeule) then a new director (Reuppel) not long after that. In order to get the museum back on track you need time. From the beginning I felt that I could achieve that only by doing certain things. We got a bit side tracked when we undertook climate control because we were already under consideration for a grant initiated by my predecessor. It was an issue that had to be dealt with at an early stage of my becoming director. There were a number of other things we wanted to achieve.

People think that it’s just a matter of appointing the new man to get things right. To put together a major exhibition, for example, you need a lead time of at least two years. When you go past initial projections people get impatient and say “they don’t know what they’re doing.”

There were two problems that I saw as the most immediate. The first was that we had a horrendous deficit. At that time, it was some $600,000 a year. That drains all of your resources. It eats up unrestricted endowment. You can change that in a year but that does great harm. You can take an institution and say let’s chop off $600,000 from the annual budget.

In the past five years, gradually, we reduced the deficit. Last year, for the first time, we operated in the black. I went to a large foundation and was told “Don’t bother to come if you have an operating deficit. Institutions with operating deficits are losing propositions.” It is important for museums to put their houses in order. To operate within your means. So that was our first priority.

Also, I wanted to create a friendlier and more hospitable atmosphere. For that you need the help of everyone. You need the help of staff and to change a lot. For example, the museum has traditionally had a guard force of relatively advanced age. This is not unusual for museums. It’s not a job that pays well. You tend to get people who have had other jobs for a long time. They are generally middle age or past that. This causes friction between generations.

One of my sons had red hair down to here. (Gesturing to his waist). Lots of people in the museum didn’t know he was my son. When he visited, he got flack and nasty remarks from the guards. It’s useful to get the feedback he gave me. We have older guards who are loved by the public. But, when there was turnover, we replaced them with younger guards. We hired artists and students from the Museum School. Each summer we have a staff show at the Museum School. These artist guards have a more friendly interaction with unconventional visitors.

Another idea was to make the museum free to all in December. That brought people in who haven’t been here in a long time. That resulted in a change and drop in the age of our average visitors.

CG You appear to enjoy these changes. On busy Saturdays I have seen you at the information booth directing traffic and handing out brochures. You like directing visitors to special exhibitions.

JF I’m here at least one day on weekends for a variety of reasons. A large percentage of visitors come on weekends. It’s as high as 50% on those two days. Particularly because of free admission on Saturday mornings. That’s been a great success.

CG That’s when I come with my students. The guards all know me and some are quite interested in my comments. If I start a tour with 50 students there may be 150 as people in the galleries join in. At times I feel like The Pied Piper.

JF The best way to keep in touch is to walk around with people and see what they are interested in. There have been very busy weeks particularly after the opening of The West Wing.

When the Asiatic Wing reopened, we had a special exhibition Living National Treasures of Japan.

CG I much enjoyed the demonstration of master sword making. (There was a hut/ workshop set up in a courtyard.)

JF (A staff member tended to a ficus tree in his office.) Plants and flowers make the museum much more humanistic. The women’s committee has done a fantastic job and they raised funds to endow their work. We have special programs Free for All and Art in Bloom. It’s important to know what’s going on here. Two hours in the information booth on Saturday, I assure you Charles, will tell you a lot about the public.

CG In the era of war and colonialism museums were where nations put their loot. Lord Elgin stole the sculptures from the Parthenon that ended up in the British Museum. The army of Napoleon took what was left, as well as other classical treasures for the Louvre. In Whitehill’s history of the MFA he refers to the acquisition of “Burning of the Sanjo Palace,” one of the national treasures of Japan. He talks about a letter in which if the Emperor asked for the scroll, they (Ernest F.) Fenollosa (1853-1908) and (William Sturgis) Bigelow (1850-1926) would be obligated to hand it over.

JF Yes, of course, I know the letter. It is very interesting.

(“The Burning of Sanjo Palace,” Heiji Monogatari Emaki, Kamakura period. 16.25in x 22ft 9in, 13th Century. Provenance: Before 1878, Honda family, Japan. Acquired in Japan by Fenollosa in 1886, sold with the Fenollosa collection to Charles Goddard Weld (1857 -1911), bequest of Weld to the MFA. Accession Date: December 7, 1911.)

CG There is also the matter of the Catalonian Chapel.

(Removed from a small, rural, Romanesque, Spanish church. It was dismantled and shipped to Boston in crates marked parmesan cheese. When the loss was discovered all similar murals were removed and installed in The Museu Nacional d'Art de Catalunya in Barcelona to prevent further theft. The example in the MFA is the only one not in Spain.)

JF Let me start by saying that times have changed. Personally, I’m not sorry that times have changed. We have made progress rather than taking a step back. I would be happy to say how I came to that realization. When I was a curator here, I bought a very fine statue from India.

CG The Shiva?

JF Yes. Someone hinted that it had been stolen. I started an investigation. I found that, indeed, the piece is mentioned in a few books in which it had been published. Including a work by (Ananda Kentish Muthu) Coomaraswamy (1877-1947 former MFA curator of Asiatic Art). By doing that research I found that the piece had been owned by a museum in India.

Pieces can leave museums under all kinds of circumstances. There is a lot of semantic confusion when you speak of a stolen work of art. The definition of stolen often depends on the nationality of the person who uses that word. Perhaps, in the most extreme example, the government of Sri Lanka takes the following position. Sri Lanka, the former Ceylon, gained its independence in 1947. Look here, they have the right to their opinion and I’m not quarreling with that.

They maintain that any piece that left the country before 1947 is stolen because it left without the permission of the government of Sri Lanka. Because it did not have a voice in those decisions. They sent an art expert to all the major museums in the world to catalogue all works from Ceylon and later Sri Lanka. When that was done that went to UNESCO. They said that all of the works were stolen and they asked that they be returned.

Coomaraswamy was from Ceylon. They would claim that anything he brought with him in 1918, since it was before 1947, could rightfully belong to them. They would feel that they had a claim to that. This is something that I would question.

If, however it was stolen, as you and I understand the word stolen here in the United States, I think then that there would be nothing standing in the way of returning the object to the country that it comes from. I do not want to have in my museum something that was stolen from someplace else. You wouldn’t handle stolen goods as a private person. I wouldn’t handle stolen goods as a museum person.

I went myself to the museum in India to verify the account. I visited with a group of tourists and asked to see the objects of a particular excavation. I was informed by the director that they had been stolen from the museum. There were newspaper accounts of the theft.

CG Did you identify yourself during that visit?

JF No, I did not. I wanted to form an impartial opinion. But, look here, I was only a curator at that time and I wanted to present the issue to the museum. This was a clear-cut instance of theft. The museum is located in Calcutta. There is such a level of human misery that it is difficult to blame the thieves. I was profoundly moved that we had a piece that was stolen in that way.

I came home and proposed to the director, Merrill Rueppel, (died 2011 at 85) and he was most cooperative in this matter. We returned the piece to India. They were enormously grateful. We were the first to know and brought it to their attention. I really felt that this was a piece that I could not longer enjoy having,

As museum director I have been involved in returning pieces on two occasions. How could we have known that a piece we had acquired, a head, was chopped off a statue in Rome’s Capitoline Museum? The piece was not published. This is something that is discussed a lot in the enabling legislation. At this moment the United States is implementing the legal framework of the UNESCO convention.

One of the points is, that if you have had a piece in the basement for twenty-five years, then bring it up and say, look here, this happened twenty-five years ago, that’s not considered to be fair. And I agree.

If you publish a piece as soon as it is acquired. You don’t hide it. It’s published in an annual report and a catalogue. If there is anything wrong about the piece you will soon hear about it. We published the Roman head in a catalogue. The director of the Capitoline Museum wrote to us. I responded that “Fine, we will be happy to return the piece to you.”

CG Isn’t it true that other than the Raphael incident (of Perry Rathbone) that has been the standard practice of your predecessors?

JF Forget about the Raphael incident. Times have changed. I’m not going into that Raphael business.

CG Well then, what is your position on returning the Catalonian Chapel to Spain or Sanjo Palace to Japan?

JF Well, OK, I was coming to that. With the Chinese and Japanese, for totally different reasons, the issue is no longer a real issue. With the Chinese everyone knows that during the period of political unrest in China, basically during the end of the Imperial era and the Ching dynasty, let us say from 1870 on, China was in turmoil. Foreigners were all over the place. All kinds of objects that would never leave today left at that time. Those who were engaged with this at that time felt that it was perfectly alright.

I can give an example of how that mentality has changed. A French orientalist, Paul Pelliot, went to Dunhuang, China which had a cave in the desert which had been bricked up. It contained a huge library of Buddhist scrolls, texts and other writing. The works had been placed there around 1,000 A.D. The library was discovered early in the 20th century. This material was acquired by the Bibliothque Nationale in Paris.

(When the Library Cave, known as Cave 17 from the Mogao Cave Complex at Dunhuang, China, was opened in 1900, several tons of an estimated 50,000 manuscripts, scrolls, booklets and paintings on silk, hemp and paper were found literally stuffed into it. This treasure trove of writings was collected between the 9th and 10th centuries CE, by Tang and Song dynasty Buddhist monks who carved the cave and then filled it with ancient and current manuscripts on topics ranging from religion and philosophy, history and mathematics, folk songs and dance.)

He was later asked if he had regrets about this after the War. He said that “There was one book, that after all the foreigners had left.” It was a very rare book of which the first five pages were missing. Although he was brilliant linguist, he failed to recognize it. A Chinese scholar published about the book. Pelliot then said that “I regret that I didn’t take that book.” That was the mentality of that time. My teacher published his remark but not in any way as a criticism. They had absolutely no regret about this.

CG That was the Robber Barons era of museums.

JF Well, in a way. There has been very thoughtful writing about this by Arthur Waley. He says that what contributed to this was that many of the things taken in Asia, scholars who did that saw a certain justification. These Buddhist treasures came from an area that is now Islamic. The Islamic tribes that live there have no respect for ancient Buddhist treasures. They chopped out wall paintings and took them to Berlin. In turn they were destroyed during the bombing of WWII. What happened were very bad.

(Arthur David Waley CH CBE (born Arthur David Schloss, 19 August 1889 - 27 June 1966) was an English orientalist and sinologist who achieved both popular and scholarly acclaim for his translations of Chinese and Japanese poetry.)

What is the difference between China and Japan? Since 1945 and 1950, with the establishment of the People’s Republic of China there have been great discoveries of treasures that completely outclass anything discovered previously. For the Chinese the question of looted treasures had become moot.

For the Japanese it is different. In this respect I must say that the Japanese are among the most enlightened people in the world. If you must establish a law that has nothing may be exported, that makes of any one dealer who sends important works abroad, a criminal. It drives legitimate art dealers underground. You must give an art dealer a chance to make a legitimate living within the law and arguably making a larger amount illegitimately. Those laws mean being forever a person who may go to jail and may even be hanged in some countries. That is still done.

CG Do you know of instances where art dealers have been executed?

JF I know that in China they have executed art dealers. Yes, they have. I understand that they have done this. Especially in the beginning when they wanted to establish their authority. If they have a choice most art dealers will settle for a compromise. They are reasonable beings. One of the good things about the Japanese system is that, rather than seeing the art dealer as a criminal, they regard them as people with whom they have to cooperate for the protection of property.

The Japanese see collections of work outside their nation as cultural ambassadors. I am personally very grateful for this. It would seem, and Whitehill quotes a letter to the same, that Fenollosa and Bigelow were genuinely fond of Japan and the Japanese. In no way did they want to hurt that country. They exercised a considerable amount of restraint. They probably could have carted off anything. But they were much more aware of the role of art in traditional Japanese life than Pelliot was in China. When you think of his remark about the book it is quite different.

They (Fenollosa and Bigelow) lived in Japan for a very long time. They are both buried in Japan. They felt that what they were doing was the right thing. That restraint means that we do not have The Elgin Marbles of Japan. We don’t have The Elgin Marbles in our Japanese collection. In other words, a piece without which that country believes it cannot honorably live. If you see what I mean.

When the Greek actress Melina Mercouri was asked about The Elgin Marbles she said “I do not call them The Elgin Marbles, I call them The Acropolis Marbles.” The acropolis, of course, stands at the very heart of Greek culture. I can understand her point of view. I am extremely grateful that, although we have extremely important works of art, we have nothing that I would call, you know, in the category of what you are calling “The Elgin Marbles.”

CG Yes, but isn’t it a fact that the MFA owns works that are regarded among the greatest national treasures of Japan?

JF Do you know where Sanjo Palace is at this time?

CG Japan.

(Until fairly recently it was displayed in a long horizontal vitrine. It was covered by a cloth which a visitor had to push back to view the work. Most visitors likely passed by with hardly a glance at one of Japan’s greatest national treasures. Despite the importance of the collection the Asiatic galleries get far less traffic than European painting or the American wing designed by Lord Normal Foster.)

JF It’s currently in Tokyo as part of a special exhibition. I have felt from the beginning that this is one of the ways in which we are respectful custodians of these pieces. The Chinese were always very much against the Pelliot collection in the Bibliotheque Nationale. But why? In France libraries are for librarians. Other people find it very tough to get in. That’s a concept that doesn’t exist in this country. There is a joke that Pelliot couldn’t get in to see the Pelliot collection once it was in the Bibliotheque Nationale. Of course, that’s an exaggeration.

CG There was a recent incident when Mexican national stole an Aztec Codex from the Bibliotheque Nationale. When he brought it home he was celebrated as a hero.

JF What I am saying is that, if you want the nation from which the pieces originate to be persuaded that it is a good thing to have them, rule one is: The works have to be accessible to scholars of the country of origin. Within reason of course but you have to give them access. That’s one thing. Another is that you share it with the nation of origin as much as possible.

Perhaps you don’t know what’s special about the current exhibition in Tokyo. I was overwhelmed when I first found out about it.

The Japanese have a large sum of money toward our project to climate control the Asiatic galleries. They wanted us to preserve that collection here for future generations. The Japanese government came through with that money. There are few things in life I have been as happy with as that. I felt that we had to do something special for them after they had done that. There was one thing that had never been done. I will explain to you exactly how it happened as it is important for you to understand.

The museum accepts a collection as a donation or a gift. There was a gift with certain restrictions. When the donor dies it is very bad to break their rules. I have confidence that when we negotiate with people who are giving us things that they do not attach conditions. Once we accept a gift we must abide by those terms. Even though they are no longer alive we can’t change them.

Dr. William Sturgis Bigelow gave his collection to the museum in 1899. He had promised Weld, who bought the Fenollosa collection, that if he would give it to the museum he would give the Bigelow collection. When 1911 came, and Dr. Weld died, and the collection was actually given to the museum, Dr. Bigelow felt that he had to act right away so that nothing prevented the collection from going to the museum.

People often assume that things are given to museums as tax deductions. The income was established in 1912 or 1913. (In 1913, the 16th Amendment to the Constitution made the income tax a permanent fixture in the U.S. tax system.) The Bigelow collection was given before then. I believe that tax deductions were put in place in 1917.

Bigelow could have used a tax deduction I can assure you. He gave the collection to the museum and later a considerable sum of money. He did this free of any restrictions. He was a trustee. It was clear to him that if you appoint the right trustees you don’t have to set restrictions that might later work against your own best interests.

Two years after Bigelow died, in 1928, at the request of a friend of Bigelow’s who gave pieces to the museum, he gave pieces with the restriction that they never be exhibited outside the museum. He requested at that time that the trustees rule in a similar manner regarding the Bigelow collection. So, as of 1928, the Bigelow collection could not leave the building.

(In 1921, the brothers William S. and John T. Spaulding donated their collection of over six thousand Japanese prints to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, but with an unusual condition. In order to preserve the delicate colors of the woodblock prints, which fade rapidly when exposed to light, they specified that the prints must never be exhibited in the galleries. Fontein did not identify the collector making the 1928 request of the trustees. But it may have been one of the brothers.)

The first exception was made at my request when I discovered that Bigelow himself had sent his sword collection back and forth to Japan to have it polished. The rule was well established that anything that we can’t repair or restore here can be sent to conservators in Japan. A number of pieces from the Bigelow collection had been sent back including the Kibi Scroll. They were shown in the Tokyo and Kyoto national museums.

("The Scroll of Kibi's Adventures in China," Heian period, 12th century. Provenance: By 1441, Oshio Hachiman Shrine, Wakasa Province (now Fukui Prefecture); probably acquired from the shrine by the Sakai family, Lords of Wakasa Province, and passed to Sakai Tadamichi (d. 1920); to his son, Sakai Tadatae (b. 1883 - d. 1939); 1923, sold by Sakai Tadatae at auction, Tokyo Art Club, to Toda Yashichi, 2nd (b. 1867 - d. 1930), Osaka; to his son, Toda Yashichi, 3rd (Toda Rosui; dealer, b. 1892 - d. 1942), Osaka; 1932, sold by Toda Rosui, through Yamanaka and Co., New York, to the MFA. Accession Date: July 7, 1932 by exchange.)

Other than individual pieces the Bigelow collection itself had never been back in Japan.

A few years ago, I was in Kyoto for the opening of an exhibition of ours. At that time Boston’s Sister City Committee, led by Mayor Kevin White’s wife Katherine, was in Kyoto for the opening. The following day on the program was a visit to the Hymyo-in temple where Fenollosa and Bigelow are both buried. They died here but were cremated and their ashes sent there. That’s where they had spent the happiest days of their lives.

I went with the group to the cemetery, Their graves are well kept in beautiful surroundings. While standing by their graves I thought “If you put in your wills that your ashes be sent to Japan I cannot imagine that you would not want your collections to return at least once. I honestly felt it was something we should do on day.”

When we considered an appropriate time to reciprocate this was it. This was the first gift by the Japanese government to a foreign museum. They have since given money to other museums: The Metropolitan Museum, Asia House, The Smithsonian. Ours’s was the first ever gift to a foreign museum. I felt that we had to do something so I went to the trustees. There is a letter which Bigelow wrote in 1902, 24 years before he died, that states that he wasn’t so keen on exhibitions.

You have to realize that international exhibitions in 1902 were very different from today when they are common. That, and that his ashes were sent to Japan, were important considerations for me. That’s what I conveyed to the trustees and they immediately agreed. It this was a restriction that Bigelow imposed, I am the first to agree and uphold what the trustees had voted on. But I feel that this was a matter of honor, especially with someone who had been as generous to the museum as Dr. Bigelow. In this case, I felt that the restrictions had been imposed by trustees themselves, so the contemporary trustees could lift them if they chose to do so. With that request I went to them and they lifted the restriction. That’s why, for the very first time, pieces from the Bigelow collection are on view in Tokyo.

CG How long was this project in the works?

JF The idea first came to me four years ago when I visited the graves. I officially took it to the trustees about a year and a half ago. After a vote by the trustees I approached the National Museum in Tokyo. I think the trustees were wise. They did not lift restrictions to the Bigelow collection but they made an exception. The only exception is for Tokyo and Kyoto national museums. Just this one time and that’s it. It’s very exceptional. Of course, other trustees and my successors may think differently.

CG How many pieces were sent?

JF Eighty.

CG What was the insurance set for such priceless works?

JF It’s a figure in Yen. We worked that out with colleagues and a Japanese firm is covering that cost. The figure looked like (laughing) such that I didn’t know what it was. I had to use a calculator to figure it out. The Japanese, Chinese and Koreans count large numbers in units of 10,000 rather than 1,000. The result is that back and forth you constantly have to write down the numbers. There are many zeros to figure out. As with any large exhibition the evaluations are in the millions.

CG If “Burning of the Sanjo Palace,” hypothetically, came to market what would it be worth?

JF Last year there was a similar on available in Japan. It was a work very similar to Sanjo Palace and the value was in the range of $5 million to $8 million. In other words, as expensive as the most expensive Western paintings. One had to bear in mind, however, that Japan is now a very affluent country. They now have collectors willing and capable to put up very large amounts of money. Were something as significant as Sanjo Palace on the market I don’t know of a Western museum that would be willing to outbid the Japanese.

CG Except, perhaps, The Getty Museum.

JF (Laughing) You will have to ask John Walsh about that.

CG Thank you for a complete and adequate answer to my question.

JF The basic points are: Make it accessible to the country of origin. Show it as much as possible. Take care of the works of art in such a manner that the country of origin has no complaint. Our works now in Tokyo have been superbly preserved. Our chief conservator, Noguchi and his staff, have worked on this for years.

CG What was the response to the exhibition? There was a new item in The Globe.

JF I was very pleased by that. If I start sending out press releases from here we are just blowing our own horn. To see it datelined Tokyo particularly pleased me. The day prior to the opening there was a visit scheduled for the Prime Minister of Japan. It turned out that he was very knowledgeable. I spoke with him and it was wonderful to see that. Having him come provided a certain quality of publicity. There are 5,000 to 6,000 daily visitors to the exhibition.

Now with the UNESCO convention and enabling legislation going into effect very soon that’s the end of acquiring great archaeological treasures for Africa, South and Middle America.

CG Turkey.

JF The countries of the Mediterranean, all those countries, it’s just going to stop. Once that happens, it’s no longer our job to smoke out the last masterpieces and grab what hasn’t yet been picked up. I am fully aware that there are other museums which do not have the great collections that we have. So, this might sound arrogant. I am fully aware that other people do not agree with me on this issue. But I feel that exhibitions, conservation, and research of works of art in our collections will take priority over acquisitions.

CG In your opinion should the British Museum return its Elgin Marbles to Greece?

JF It’s not fair for a museum director to go to another museum director and point to pieces that should be returned. The British have a responsibility to make up their own mind.

CG There is sustained and mounting pressure to make that happen.

JF During WWII it seemed that Rommel was about to take Egypt. The Germans were preparing for that eventuality. Through back channels there was contact with the Egyptians. They stated that they would be in Cairo in a matter of months. They wanted to sit down and work out details before their arrival. Something like that. Do you know how the Egyptians answered?

They were unwilling to talk with the Germans for as long as the head of Queen Nefertiti remained in Berlin. I just give you this as an example.

CG The Germans were excavating at Amarna at that time and a lot of strange things occurred before they pulled out. Many works were looted and ended up in the art market. That’s how a couple of pieces came to the MFA. I was there when a dealer brought a piece of relief that matched perfectly with one in the MFA.

(In 1999 the MFA mounted Pharoahs of the Sun: Akhenaten, Nefertiti, & Tutankhamen curated by Rita Freed. It surveyed the unique Amarna period and style of Egyptian art.)

JF Those kinds of things happen. If that’s what we are getting into there are things that I can tell you that must be returned. But I will only give examples of things that must be returned. It’s not the place of a major museum director to say what must be returned by other museums.

CG Although you agree in general that there are many things that should be returned.

JF In the 19th century when the British conquered Mandalay, in Burma, they carted off the royal treasures which were shown for many years in the Victoria and Albert Museum. In 1947 Burman regained independence. In order for a free Burmese government to have legitimacy the crown jewels had to be returned. They were taken during a punitive expedition and belonged to the royal family of Burma. So, the British decided to return the treasures. The Burmese were so overwhelmed by the gesture that they donated one of the finest pieces to the V&A.

Around 1903 the Dutch launched a punitive expedition next to Bali. A rare piece was found in the palace of the Sultan. It is a unique manuscript and rare example of Indonesian literature. They took the crown jewels of the sultan, large diamonds. It was glittery stuff but not of great aesthetic value. I was a young curator in the (Dutch) museum and argued for the return of the treasure to Indonesia. I felt that during a time of independence that ought to be done. There was much bitterness between the two countries. It was not possible at that time and a great opportunity was lost.

The Indonesians later demanded and got the treasure back. It would have been more elegant if that happened in a better manner. A group of sculptures from the temple of Singosari in Eastern Java were taken to Holland in two ships in 1819. One of the ships perished in a storm at sea. It lies at the bottom near the Cape of Good Hope. The pieces on the other ship were shown for many years at the National Ethnographic Museum in Leyden. One statue represents a royal person in the guise of the goddess of wisdom.

To have a royal person in divine form is the kind of piece that belongs to a nation which has become independent. It’s the kind of a piece that a nation must feel strongly about. When I went to their museum in earlier years there as a plaster cast of that object as a reminder of what was missing. Now the plaster cast has been replaced by the original. I am pleased by that even though it was no longer in my museum. It is difficult to accept, however, that a country has the right to everything that was produced in it. That, I think, goes too far. But there are particular works that have historic, sentimental and symbolic significance that are the essence of the identity of a nation. If you have such objects in your museum it is difficult to justify that.

CG (Pulling out of my pocket a one-dollar bill with the head of George Washington on it.) You mean like this?

JF (Laughing) I have always taken a neutral position on that. (Joint ownership of Gilbert Stuart’s Washington portraits with The National Portrait Gallery.) I came to this country seventeen years ago. I liked the paintings. But the people you would expect to be very keen to keep them here, apparently, were not. And people you wouldn’t expect surprisingly were. The wish to have them here was not shared by all Bostonians. But you can’t find a Greek citizen who doesn’t want back The Elgin Marbles.

CG You say there are areas of great strength in the collections and accordingly a shift away from acquisitions. But there are areas for which this is not true.

JF Yeah, yeah, contemporary art.

CG That glaring need continues to be controversial. During his tenure Perry T. Rathbone never appointed a curator of painting. Now there are three curators covering the former domain of Rathbone and (curator of medieval and decorative art) Hans Swarzenski. As evidence of your significant appointments John Walsh (curator of European painting) has now been made director of the J. Paul Getty Museum which has one of the nation’s greatest endowments. Ted Stebbins for American art, and Kenworth Moffett for contemporary art, are renowned scholars. The collection of American art is one of the best in the nation. But after 1900 American and European art in the MFA is not on a par with major American museums.

JF You will see a sensational change with the recent acquisition of the (William and Saundra) Lane Collection. But let me respond as I know what you are talking about. First, I do not blame my predecessors. Two predecessors did not appoint a curator of painting.

As you have gathered from my remarks on importation of works of art from abroad. Since I am myself an Orientalist I was involved in a lot of importations. My personal interest, and not as a museum director. The things I have alluded to like giving back to an Indian museum, and seeing the poor devils there being robbed. Even I was surprised at not being robbed when I was there, does change your attitude toward acquisitions. I am now having more opportunities to be in Asia than I had in the first twenty years of my career. Through that experience I have come to appreciate works in their own habitat.

I really don’t see the job of a museum director to be sitting with art dealers, drinking coffee, and smoking out the last remaining masterpieces. I recognize that colleagues might have a different view of that.

Acquisitions take research and enormous amounts of time. A director should leave that to curators. I am interested in painting but have no expertise. If I had to do the buying there would be mistakes. Though perhaps I might have bought a few nice pieces. I wouldn’t be any better than another amateur.

(Significantly, no senior curator, other than Swarzenski a medievalist, advised Rathbone, a generalist, on acquisitions. Briefly, Thomas Messer, then director of the ICA had a hand in a couple of prescient acquisitions. A merger of the ICA as the contemporary department of the MFA never happened. Only as one of his last acts in 1970 Rathbone appointed Kenworth Moffett as the founding curator of modern and contemporary art. One may only speculate what might have been.)

For a large museum with painting as a large part of what attracts an intelligent audience, I felt that we had to have a good painting department. An active painting department has to be the core of the museum. I did my best to attract the best people. That has led to the success and quality of the department. I see my task as helping them to get funds. Occasionally, I act as an arbitrator because there are competing demands on limited funds. I get involved when there are complicated issues as there often are. We now have three curators of painting.

The museum had to start from scratch with contemporary art in 1970. There are advocates that want as wide a net as possible to gather as much as possible. For a museum with limited resources it made sense to collect in depth in a relatively limited area. As you know a frequent criticism is that the contemporary department is too one-sided. You have heard this. People have to realize that. I’m not saying that we should stay forever in this limited area.

CG The exhibitions policy for contemporary art has also been narrow.

JF We have been looking at that and lately there have been a few changes.

CG It has been pointed out by Boston dealers and collectors that when representative works of art are offered to the museum they are not accepted by the museum unless they conform to aspects of formalism. Even as gifts.

(Phil Guston at the time commuted from New York to teach weekly at Boston University. He was then creating figurative expressionist works that are now prized by museums and collectors. Allegedly, he offered the pick of his studio to the MFA. Instead Moffett asked for an earlier abstract expressionist work. The artist declined. The MFA later acquired a Guston of the later style which is not the best example of that period.)

A prominent collector sent a letter to the board of the MFA that he will not give works to the museum because of its narrow acquisitions policy. There was an article in the Globe last week by Christine Temin about that issue. Did you read that?

JF I was away last week and didn’t see it.

CG It was a review of a Danforth Museum exhibition that Moffett curated.

JF Oh sorry. Yes, it did see that article.

CG In the ten plus years of the Contemporary Department it has collected in a narrow frame of reference.

JF Well, I can see that, but look here, I know very little about contemporary art and I have undertaken my own education. One of the aspects of being director is that you have to address issues you are not familiar with. I do not think that many people are aware of how limited are the resources of the museum.

CG Well then, why refuse gifts?

JF You sometimes hear that but it is more talk than reality. I don’t know of any major gifts that have been rejected. Funds for acquisitions are limited and must be shared by all departments including European, American and contemporary. When we started the contemporary department in 1970 there were a lot of expenses entailed in getting it up and running. There were staff, office space, and storage as well as establishing an exhibitions policy. That’s where a lot of money went.

My predecessor (Rathbone) decided that we had to start somewhere. There was a decision to limit acquisitions to color field painting and realism. At the time this decision served a good purpose. Now, however, it is a good time to see if you have achieved your ten-year objectives. And to look to the future. We’re looking at everything and there is a lot or room for improvement.

The very nature of contemporary art is such that we shouldn’t avoid controversy. Dead artists can’t speak for themselves and they aren’t disturbed by discourse. On the other hand, if we had started out on a broad front we wouldn’t be where we are today. I’m not saying that we should follow the same course for the next twenty years. Any curator with certain ideas has an impact that is felt for many years. Overall, we will retain a balance. Over a long period of time the idiosyncrasies are unavoidable. When there is a fifty year span it is likely to have a number of curators setting a unique character to the collection. The museum is in the business of taking a long view.

I honestly believe in and admire the work of David Ross who is doing a splendid job for the ICA. We work with the ICA on a very cordial basis but we don’t try to duplicate what they are doing. They, for their part, shouldn’t try to do things that we are better at. As you well know there are serious gaps in our 20th century collection. We would love to acquire a Leger or a Mondrian. But those lacunae are the most expensive ones to try to fill.

CG It’s costly to play catchup.

JF You pay through the nose. The cubist work that we own by Picasso cost well over a million dollars. That purchase has tied up acquisition funds for a number of years. As a matter of fact Charlie, I bought the Picasso about a month after our last interview. It was behind you as we talked but you never saw it or asked me about it. You haven’t made that mistake today noting and discussing the Dove hanging in my office.

As I recall at the time (laughing) you were kind of grumpy saying that the museum wasn’t doing anything about modern art. When you came in and sat down your back was to the Picasso. It was hanging in my office for me to have a chance to get used to it and prior to making a commitment for its purchase. You didn’t notice it. I was rather nervous about it because negotiations were then in a sensitive stage.

A few hours later, during another appointment, Robert Hughes of Newsweek walked in and right away said “Oh, so you’ve got this Picasso.” (Laughs) I must look up the date of our meeting in my appointment book. I will get it to you.

(Pablo Picasso, “Portrait of a Woman,” 1910, was acquired in 1977.)

CG How is the MFA different today from what it was before you became director?

JF Gradually our constituency has become more solid among the people of Boston. Our attendance is now twice what it was. People come in larger numbers and more often.

CG Given that there is a large audience for modern art hasn’t it been costly to neglect that area?

JF You pay through the nose for being late. If you want to show people that you are a serious museum you must set an example. I thought that Picasso was a good picture. It also signified that we were making an effort to get into modern art. I agree that our collection of modern and contemporary art is weak. But if you put it together with the holdings of the American department, prints and drawings, you begin to scrape it together.

Also, do you notice the large (Frank) Stella that hangs in the galleria? That painting is on loan to us from Graham Gund. That painting belongs there and Gund has been agreeable to lend it to us. Through loans and acquisitions we are building a collection. There will be many surprises when we reopen the Evans Wing. I may assure you of that.

CG In the 1970s the MFA missed out on the international tour of Treasures of Tutankhamun. It was rumored that Boston initiated the project. This was a particular snub considering the important of the museum’s renowned collection of Egyptian art. There was an unfortunate pattern regarding touring blockbuster shows. The reason given was that Boston lacked climate control. Where does the MFA now stand in regard to being included in these major touring exhibitions?

JF The Government and endowments that underwrite these large shows are looking for a regional spread. New York, for example, offers more resources to do these shows. In that sense the East Coast with NY and D.C. is spoken for and there is the issue of relative proximity to New York which works against us.

As much as six or seven years of planning go into those major exhibitions. Regarding the Tut show we couldn’t have handled it because of the expense and security involved. Even the Pompeii show drained our resources. Our greatest success was that show which drew some 450,000 visitors. That finally outnumbered our Andrew Wyeth exhibition. Even the income from that many visitors doesn’t cover the cost. But we don’t look at shows just in terms of attendance. For our exhibitions of (Jean-Baptiste-Siméon) Chardin and (Camille) Pissaro, for example, we had the highest level of quality. The (Thomas) Eakins show that we mounted was named “The Show of the Year” by the New York Times.

CG May I ask your age and when you plan to retire?

JF I will be 56 this year and not seriously looking into long range planning. I enjoy what I do but haven’t made long range plans. There are projects which I must first see to completion such as climate control. We have finished the Asiatic Wing and now must start work on the Evans Wing of Painting. There are things I want to do and can’t postpone until I retire.

(Fontein (22 May 1927 - 19 May 2017) from 1966 to 1992 served as curator of Asiatic art at the MFA. He was director from 1975 to 1987. From 1945 to 1953 he studied far eastern languages and Indonesian archaeology at Leiden University.)

CG The museum’s Asiatic collection is regarded as the world’s most comprehensive. A curator that would make you one of the foremost in the field. As such isn’t it difficult to give up research and teaching to assume the responsibilities of director? To what extent do you miss your role as a curator?

JF When feasible I do some scholarly work and teaching. But teaching requires that you have a fixed schedule and that’s not possible given the demands of my position. Doing research, however, is more independent. As the museum’s director I recently participated in a survey. It stated that there have be some 237 doctorates in Asiatic art awarded since 1945. The survey asked how much of what I do now is what I was trained for?

Today I deal with administration, budgets, public relations, arbitrating disputes between curators, and making executive decisions. I derive a great deal of satisfaction from doing this.

Perhaps I am different from other museum directors because, at heart, I am basically a populist. On the other hand, my predecessors had backgrounds in painting. But the museum has other great collections: Classical, Egyptian and Asiatic.

People have accepted me for who I am. I chat with people and have contact with the public. That way I find out what’s going on from the time I put into that. When there is an open curatorial position, I try to get the best person available. That influences what we collect. Gradually the institution changes. I find it necessary to have colleagues who see the museum as more than a job. The best people on our staff understand that. From 1947 to 1955 I served as a part time assistant in a museum and the pay was very low.

CG Today you earn $75,000 a year as director.

JF I didn’t go into this profession to make money or to be director. It was like taking a vow of poverty when I started and I was willing to do that. It was not a sacrifice. As to my salary there is an obligation to publish that information as director of a non profit institution. Boston Magazine obtained that through the Freedom of Information Acts. I am all for freedom of information and in that sense must pay the price for full disclosure.

(Salaries are stated in annual tax reports which are available to the public through the charity desk of the office the Attorney General. That’s how I discovered, for example, that MFA curator of European Painting, John Walsh, was paid an annual stipend of $25,000 by the foundation of the collector William I. Koch. That was a third of Fontein’s annual salary which was considerable for the time. I asked Fontein for a comment when we published that information with editor Jon Lehman in the Patriot Ledger. Fontein said that he was aware of the arrangement. Walsh, who was speculated to succeed Fontein, had just departed to become director of the J. Paul Getty Museum. Works that Walsh acquired for Koch were briefly exhibited at the MFA including paintings by Cezanne and Manet. MFA director, Malcolm Rogers, later mounted a major exhibition of the eclectic Koch collection. That included displaying two of his America Cup racing vessels in front of the museum’s Fenway entrance.)

CG Thanks for your time and one last question. What do you do when not at the museum?

JF I am often here until 8 p.m. and have a late evening supper. I take off at least one day a week. So, I get by.