On Memorial Day

The New England Holocaust Memorial

By: Mark Favermann - May 26, 2008

Just like every other year, over the past weekend, there have been many Memorial Day stories on television, radio and in the newspapers. Some are poignant and some are very sobering. Generally, all are either about sorrow, remembrance or honor or all three. Often, it is about fallen soldiers, but Memorial Day is also about all kinds of remembrance of those departed. These are icons of our hearts and minds. We never seem to get numbed to this.

During this time, I began to think about the memorial as a piece of artistic recall, more a physical place, a sculptural memory object, a reminiscence environment or even an iconic symbol. These can be considered civic design or public art. It makes no difference how they are defined. It only is meaningful as a sense of place or sense of shared experience. Isn't this the way that the origins of public art and public or sacred buildings began as a show of respect to something beyond living men and women? These higher notions, these homages became in their greatest form The Great Pyramids of Giza, Stonehenge, Greek Temples, etc. Later the great cathedrals of Europe were created as were the spectacular Asian temples as symbols and sacred places. Roman monuments and archways commemorated and thus memorialized great battles.

Memorialization is a very human attribute. We remember by making a monument of some kind. Looking at the last couple of decades, there have been a variety of major memorials created. These range from Maya Lin's Viet Nam Veterans Memorial (1982) in Washington, D.C, to The Oklahoma City Murrah Federal Building National Memorial by Butzer Design Partnership (2000), to The Pentagon Memorial for the attack on the building during 9/11 by Julie Beckman and Keith Kaseman (2008) and finally to the stressfully evolving World Trade Center Memorial Reflecting Absence by Michael Arad (2011). Each is distinctive and each commemorates in a specific way. The best of these memorials are not about death but about life.

In Boston, there is another meaningful contemporary memorial--the elegant New England Holocaust Memorial by architect Stanley Saitowitz (1995). And it is a great contemporary memorial. The New England Holocaust Memorial was built to commemorate and reflect upon one of the great tragedies of the 20th Century, the Holocaust (Shoah). The Boston effort was begun by a group of survivors of Nazi concentration camps who had found new lives in the Boston area. The organizing committee is called The Friends of the New England Holocaust Memorial, and the memorial was dedicated in October,1995. Many prominent individuals from around the United States joined in the effort. Over 3000 individuals and organizations joined in sponsoring the project.

In the early 1990's, I remember seeing a very indifferent presentation of the memorial competition's finalists at the Jewish Community Center in Newton, Massachusetts. To me, very few of the designs seemed well done, polished or even professional. Supposedly, over 520 entries were received. How many of these were by children or literal amateurs is not known. At the time, I felt that the design by Stanley Saitowitz was too stark and too mechanical looking. However, none of the others appealed to me either. One by a distinguished landscape architecture professor at Harvard was a rather clumsy positioning of large boulders. At the time, to me the competition finalists seemed uninspired. I also feared that the resulting piece would just be corny, maudlin and not beautiful. Clearly, I was wrong about the Saitowitz submission.

Interestingly, the chairman of the New England Holocaust Memorial competition judges was star architect Frank Gehry. Apparently it took about four years to raise the money (over $2 million) to complete the project. Though I was earlier on personally skeptical about it, the memorial is rather wonderful. As in any of the best public projects, this memorial got better at every higher stage of its development. The earlier rougher competition sketches had little to do with the refined completed memorial.

Later when the project was completed, my major criticism was that I thought that its urban setting was somehow inappropriate. Shouldn't a cerebral elegant project like the New England Holocaust Memorial be located in a more serene park-like setting? Why should it be placed in a setting so close to commerce and the urban grit of the City of Boston? I was wrong. Apparently, I was not the only one who felt that the memorial was not up to snuff initially. The Boston Globe's architecture critic-for-life Robert Campbell panned the project when it was completed.

He stated that he felt sympathy for the architect/artist saying that the Holocaust was too vast to memorialize, that today we lack a common visual language of public symbols and that it certainly was not great art or great architecture. Campbell feels that the purpose of a memorial is not memory but catharsis. That's his personal opinion. Apparently, that helped to win him a Pulitizer Prize for criticism. But he was wrong then as I was wrong. This memorial works rather brilliantly.

The memorial's designer was born in Johannesburg, South Africa. Stanley Saitowitz came to the United States in 1976. After receiving his masters degree from the University of California at Berkeley where he is a professor, he established his own architectural practice in San Fransisco. Among his other project credits are the California Museum of Photography, the San Francisco Embarcadero Promenade, Mill Race Park in Columbus, Indiana, and numerous, rather unique residences. When Mr. Saitowitz submitted his design to the Memorial competition, he wrote a poetic description to characterize the design's evocative and metaphorical qualities.

Some think of it as six candles,

Others call it a menorah.

Some a colonnade walling the civic plaza

Others six towers of spirit.

Some six columns for six million Jews,

Others six exhausts of life.

Some call it a city of ice,

Others remember a ruin of some civilization.

Some speak of six pillars of breath,

Others six chambers of gas.

Some think of it as a fragment of Boston City Hall,

Others call the buried chambers Hell.

Some think the pits of fire are six death camps,

Others feel the shadows of six million numbers tattoo their flesh.

The New England Holocaust Memorial is prominently located in the heart of Boston's historical district. It is located just off the famous Freedom Trail, in downtown Boston, near Faneuil Hall and many other American history treasures. According to the memorial's website, "The site offers a unique opportunity for reflection on the meaning of freedom and oppression and on the importance of a society's respect for human rights."

It has a major vertical component of six luminous glass towers, each 54 feet high.

These sleek, transparent towers are lit internally at night. They are set on a black granite path, each one over a dark chamber that carries the name of one of the principal Nazi death camps. Smoke rises from charred embers at the bottom of each chamber. This is a reference to the crematoriums that were used for executions at the camps. Six million numbers are etched in the glass in an orderly pattern. These represent the tattooed numbers that were put on each of the victim's arm. It is also a reference to the methodical ledgers of the rigid Nazi bureaucracy. The six towers recall in a metaphorical way the six main death camps, the six million Jews who died, and a menorah or candelabra of memorial candles.

Visitors walk along a black granite path through the Memorial, passing under the towers. At the base of each tower, a stainless steel grate covers a six-foot deep chamber. Before each chamber is inscribed one of the names of the six primary Nazi death camps: Majdanek, Chelmno, Sobibor, Treblinka, Belzec, and Auschwitz-Birkenau. At the bottom of the chambers or pits, smoldering coals illuminate the names of the camps. Smoke rises from the pits sometimes creating a fog. This suggestive but not quite literal symbolism is part of the true beauty of the New England Holocaust Memorial. The design arouses memory, personal response, and collective understanding in the many visitors to the memorial.

As visitors approach the New England Holocaust Memorial from the Faneuil Hall side, he or she encounters a large black granite panel that outlines key historical events that led to the Holocaust from the Nazis opportunistic rise to power in 1933 to their ultimate defeat in 1945. As one enters the first tower, they pass over the word "Remember" inscribed in the pathway both in English and in Hebrew. To encourage a more universal understanding, information is presented about the history of that period throughout the Memorial. Inscribed along the edges of the pathway, in between each tower, are short factual statements about the Holocaust, its many victims and its heroes. This reinforces the simple physical beauty of the memorial's larger elements and its narrow though graceful space.

Something less known about the towers, is that in low winter direct sunlight, one can reach behind the glass and the numbers will reflect onto his or her own hand or arm. Was this a thoughtfully designed or accidental part of the memorial? Or was this one of the those special non-planned features that adds greatness to a public art piece similar to seeing our own reflection in the polished surface of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington?

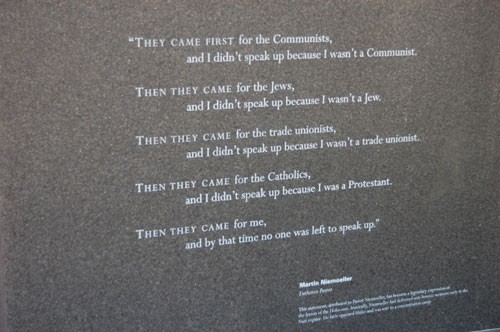

Through the voices of various survivors and witnesses to the Nazi death camps, we are asked to somehow comprehend the acts of inhumanity that can stem from the seeds of prejudice. Inscribed in the glass panels at the base of the memorial's towers are statements which represent a range of personal experiences, from the horrors of camp life to acts of resistance. As visitors leave the final tower, they again view the word "Remember", inscribed in English and Yiddish, the language of Eastern European Jewish people. At the end of the path stands a large black granite panel, bearing the poignant poetic quotation from Lutheran Pastor Martin Niemöller.

Ironically, an early supporter of Hitler and someone who gave anti-Semitic sermons, by 1934 Niemöller had come to oppose the Nazis. It was largely his personal and family connections to influential politicians and wealthy businessmen that saved him until 1937. Then he was imprisoned eventually at Sachsenhausen and Dachau concentration camps. He survived to be a leading voice of penance and reconciliation for the German people after World War II. His moving poem is quite well-known, often quoted, and is a popular model for describing the dangers of political apathy.

When the Nazis came for the communists,

I remained silent;

I was not a communist.

When they came for the Jews,

I remained silent;

I wasn't a Jew.

When they locked up the social democrats,

I remained silent;

I was not a social democrat.

When they came for the trade unionists,

I did not speak out;

I was not a trade unionist.

When they came for me,

there was no one left to speak out.

There is a tradition at Jewish cemeteries. Visitors and mourners often lay a stone on the top of a grave marker as a sign of respect and remembering. On top of the engraved panel with the Niemöller poem, there are many stones. On Memorial Day, there are certainly many stones as well.