Paul Chaat Smith: Everything You Know About Indians Is Wrong

Provocative Essays on Politics, Arts and Culture

By: Charles Giuliano - May 29, 2009

Everything You Know About Indians Is Wrong

By Paul Chaat Smith

University of Minnesota Press, 194 pages, illustrated, $21.95.

ISBN 978-0-81666-5601-1

From August 23, 2006 through February 25, 2007 the Aldrich Museum of Art in Ridgefield, Connecticut presented "No Reservations" an exhibition that combined Native American artists with non Natives working with themes that resonated with aspects of the culture. I met with the curator, Richard Klein, and discussed his strategy for what struck me as a very important project.

Previously I had started an ongoing e mail dialogue with Jaune Quick to See Smith that led to a visit with her in New Mexico and a project for an exhibition and related lectures at New England School of Art & Design at Suffolk University. Jaune created a series of new works on paper. Her lecture provided an overview of contemporary Native American art while a gallery talk allowed for intimate contact and questions from students.

Through Jaune I connected with other Native artists which resulted in another project, shortly before I retired from the position of director of Exhibitions, Native New Yorkers. Again there was a lively interaction with students meeting with the participating artists Mario Martinez and Jason Lujan. The two other artists who were unable to attend the opening were Jeffrey Gibson, whose work I knew through Samson Projects, in Boston, and Peter Jemison. It emerged that I had in fact known Jemison through a mutual artist friend in the 1960s. Connecting with Kathleen Ash Milby, a curator at the Smithsonian's National Museum of the American Indian in New York, I continued to discuss her exhibition projects and meet with other artists.

While fascinating I soon learned that researching and exhibiting Native American artists was challenging, problematic, and perhaps even impossible. It was through the Aldrich show that I first encountered the writing of Paul Chaat Smith. Given that visiting the Aldrich took some effort and expense I was disappointed not to be able to return for the panel discussion and a talk by Smith. That first essay I read was stunning and powerful. I wanted to know more and have now just finished reading the brilliant and deeply disturbing book "Everything You Know About Indians Is Wrong."

In the very last sentence of the book, in the afterward, my head snapped back when he seemed to speak to me directly "So here's some advice to all you cultural critics out there: be careful what you write." Duly noted. It was not the first or last such message. As one artist put it "You will never be one of us."

This cuts to the heart of the conundrum which Smith's book touches on in a multi valent manner. There is simultaneously the concern that there is not enough attention paid to the developments of contemporary Native American art, as well as, sharp warnings to those who would "walk in the moccasins" of the culture. It does not tend to invite deeper inquiry into the many complex aspects of Native art. Even the title of Smith's book issues that invitation to perhaps get closer to the truth as well as ridicules the non Native reader for misdirected assumptions. No, I do not want to "walk in the moccasins," sit in the sweat lodge, or have my pectorals mutilated as in "A Man Called Horse" by a Sun Dance ritual. I am intrigued by the history and culture and how that manifests in contemporary art. Smith is right on target when he states that most of the books on Native culture appear in the New Age and Environmental sections of book stores.

There is an assumption that every Native person is somehow spiritual, shamanistic, and a committed environmentalist. None of this interests me. Nor do the notions of romanticism that Smith skewers so nicely in non Native cultural projects such as the hilariously awful film "Dances with Wolves" that manage to get everything wrong. As Smith, who loves film, TV, and popular culture points out the Kevin Costner film is supposed to be about Comanches but, because there weren't enough buffalos in Comanche territory, the film was shot using the Sioux as actors and extras. These are peoples with great historical differences.

Smith often writes about the importance of film and photography in pinning down so many of the wrong assumptions about the diversity of Native history and culture. The tendency to treat Indians as all of one piece is as wrong as saying that Greeks are the same as the Irish or Albanians. There are threads, they are all Caucasians, but, as in Native culture, there are vast distinctions of heritage, language, and ceremonies. There are more than a thousand native languages and dialects. Much effort is focused on keeping them from extinction.

The Aldrich project seemed so innovative and important, creating a new paradigm for combining Native with non Native artists. I was truly disappointed when Klein said that he had no further plans to deal with the theme. As a small regional museum with a diverse program there isn't a mandate for more such exhibitions. This contrasts with the Smithsonian's National Museum of the American Indian (New York and Washington, D.C.) which only exhibits Native art and culture past and present. Because of this specialized approach, for the most part, its exhibitions do not attract the interest of the mainstream art world.

Even as an employee of the Smithsonian, Smith is frank in both his passion for and misgivings about NMAI. He was hired while the museum was under construction and worked for several years on the design of the permanent collections. This involved consulting with numerous tribal leaders. When this task was accomplished, which evoked mixed critical responses; he was reassigned to focus on contemporary Native exhibitions.

It is an ability to see all aspects of complex issues that makes Smith's writing so intriguing, insightful and deeply disturbing. When I started reading chapters before going to sleep it resulted in nightmares. The ideas were so involving that my brain would just not shut down. I switched strategy and started to read one or two chapters over breakfast allowing the ideas to work through and resolve by bedtime. I tend to be a slow reader and there was so much to absorb as the writing evoked conundrums. Including why am I doing this? Just who is Smith writing for? Is it a book to be shared by the Indian intelligentsia or the random, curious, non Native reader? Is he preaching to the choir or trying to expand an understanding of the art and culture he engages and writes about?

None of this is clear and he reveals a lot of ambivalence. I came to think that I knew him and clearly identified with a lot of his experience during the age of revolution in the 1960s but coming at it from a very different vantage point. He dropped out of Antioch College, however progressive, and joined the American Indian Movement (AIM) mostly during the aftermath of the Wounded Knee occupation in 1973.

With Robert Warrior he co authored another book "Like a Hurricane: The Indian Movement from Alcatraz to Wounded Knee." It is a theme that threads through many of the essays. He hoped the book would become the "gold standard" for thinking and writing about AIM and Wounded Knee but is disappointed that this really hasn't happened. He feels that there should be a series of books including full scale biographies of such leaders as Russell Means and Dennis Banks. Smith wonders why there have not been books about the some 500 federal prosecutions which resulted and dragged out for years.

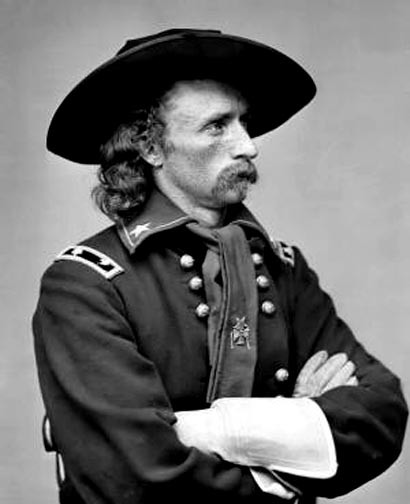

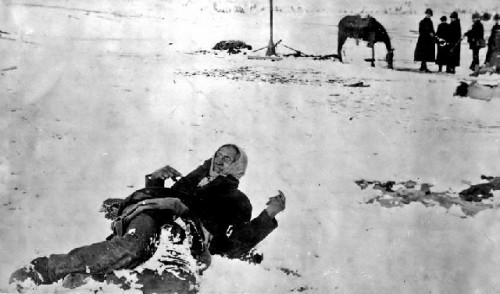

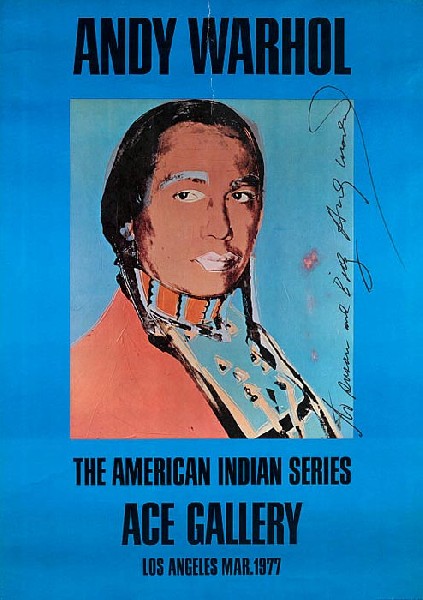

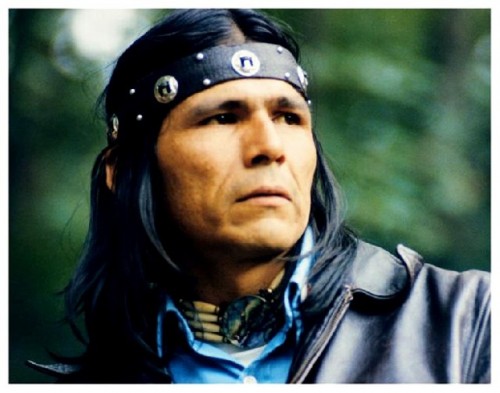

There was indeed a recent PBS segment on the Wounded Knee occupation, included in a five part American Experience series, and Smith was one of the talking heads in the narrative. It seems that the occupation occurred precisely when Nixon was consumed by Watergate and his administration had little time or interest in dealing with the domestic crisis. The Wounded Knee occupation just petered out into a kind of stalemate that saw the beginning of the end for AIM. Means went on to be a mini celebrity in film and had his image captured by Pop artist, Andy Warhol.

In many aspects the approach of Smith, the humor and biting irony recalls the late Vine Deloria, Jr. (1933-2005) the author of the best selling book "Custer Died for Your Sins." He was the most controversial Native thinker of his generation and Smith poignantly refers to his influence and ability to piss people off. It is a huge gap to fill and Smith is the most promising prospect to step up and advance the dialogue.

What I most enjoy and admire about Smith is his hipster manner of dealing with all of the ironies. Deloria wrote about the special aspects of Indian humor and I feel it here as well. But it appears to be something that Smith struggled to come to and reclaim. He was not brought up on the Rez imbedded in tribal language, ceremonies and culture. There are his misgivings about being brought up in the suburbs of Cleveland and Washington, D.C. He spent summers visiting the farm of his white father's family and the Comanche relatives of his mother. Given the Comanche practice of assimilating captives he wonders about the purity of his mother's full blood ancestry. The artist, Peter Jemison, for example is a descendant of Mary Jemison who wrote an account of being captured by the Senecas.

He speaks of pride in being an enrolled Indian with the requisite ID card. There are issues of identity that pervade many of his generation particularly those who grew up in urban environments with little sense of community. He also speaks with some disdain for born again Indians who, as adults, have discovered and identified with traces of their heritage. This also extends to the non Natives who presume to become involved with and authorities on aspects of the history and culture.

It is an issue with which I have some background. For many years I was a jazz and rock critic. That meant dealing with black artists and musicians. I got to hang out, perhaps as much as a white guy could, with Miles Davis. We shared a passion for the music and it was around when he released "Bitches Brew" which completely changed the definition of jazz. There was a hilarious dinner with the blind musician Roland Kirk and his band. Rahsann, as he called himself, was ranting and raving about the "Mother FÂ…. white jazz critics." As the band members stifled their laughter I just wrote it all down. Talk about the Invisible Man. Often I found myself a kind of target for the rage. But that seemed ok as long as I had the strength of my own identify and the ability to both absorb and deflect focusing on what seemed important.

During a discussion in my avant-garde class a female graduate student stated that "As a woman I feel thatÂ…" I interrupted her and said in essence that she could express her own opinion but was not appointed by her gender to be its spokesperson. Astrid often reminds me of male blindspots in understanding women's issues. Although I never reverse that argument. As a straight white guy I have found myself with little or no leverage in the raging culture wars. It never occurs to me to become a born again Sicilian or Irish. My Irish relatives have long regarded me as a colorful foreigner.

Identity becomes a huge issue and challenge in navigating culture. Does one have to be black to write about jazz? Jewish to comprehend the Holocaust? Gay to explore queer studies? A woman to deal with feminism? Native to understand Native art? Chinese to discuss Asian art? There are so many boundaries that, the minute we step out of our own identities, we are all strangers and trespassers.

The common thread that transcends race, gender, language and culture is our humanity. How do other people deal with the issues that involve us? We are all the people of the earth. While some cultures and traditions respect it more than others. This conflates with discussions of Colonialism and Post Colonialism. Why is there not more effort to find common ground? What is acheived by pursuing separatist agendas? With subtexts that state "You are not a part of us so you can never understand." Arguably this is true but also isolationist and reactionary. In what sense are many of us freedom fighters, cultural radicals, and seekers of truth?

Deloria was brutally hilarious in shredding the anthropologists and sociologists who descend on reservations with cameras and tape recorders. Smith relates how some of the most popular books written by Natives were created by imposters. He says that some of the books are even widely read by Natives. And he doesn't have much patience with white liberals who treat "Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee" by Dee Brown as approaching the Biblical. His point is that Brown never mentions the people who survived the genocide. Smith points out that all those folks descending on reservations in search of real Indians just blow by the ones that are everywhere. They are anonymously dressed in jeans and t shirts, pumping gas, serving food, at a rock concert, living like everyone else in the urban environment. Where you least expect them.

Partly he blames it on photography, like the images by S.D. Curtis and others, that resulted in neo romanticism fueled by movies, TV, and New Age/ pop culture. The John Wayne thing. Or Carlos Castaneda. Smith points out that there are vacations including vision quests and sweat lodges advertised in Mother Jones. We saw our share of Indian kitsch in Sedona and Santa Fe. Native women selling authentic Indian jewelry made in China. White tourists weighted down in turquoise and silver. Or Indian casino tycoons driving Cadillacs and wearing ersatz Nudie suits like Elvis and Wayne Newton.

The hipster irony of Smith's essays fully absorbed me. I loved the way he could transition from talking about the Clash to Sitting Bull. While working with AIM as a young activist he washed dishes back home in Shaker Heights. The suburbs proved to be a breeding ground for radicals and activists.

Because this book is a collection of essays, mostly written for exhibition catalogues, there is some redundancy. He keeps coming back and reworking aspects of the same narrative. His time as an AIM activist is constantly touched upon. We sense his misgivings and disappointments but they are never spelled out. Often an essay starts with anecdotes and personal insights and then well along morphs into critical thinking about an artist or exhibition. In general I did not know the work discussed and the book has only a few illustrations. Even the Aldrich essay did not give me much of a grasp of the work I viewed. Often Smith seems like the hired gun brought in to say something about a project. He has the bona fides as an activist, Native, and Smithsonian curator.

By his own admission he became a Smithsonian curator by default. It was a matter of motive and opportunity more than prior training. He is very smart, indeed one of the best and brightest minds of his generation, Native or not, but the essays also convey learning and writing about contemporary art from the seat of his pants. With no training in art history the discussion often seems limited. There isn't the depth and background to reach beyond the work at hand and make larger connections through deeper critical analysis.

This cuts back to the problem of just who is invited into the cultural dialogue. And that warning I quoted from the last line of the book. If the understanding and promotion of Native art and culture evolves to the next level there needs to be a wider dialogue with non Native critics, curators, art historians and collectors. Until then Native art and culture will continue to be a specialty of NMAI, the occasional one shot deal of a curator like Richard Klein of the Aldrich Museum, or a special issue of Art News like the one that appeared a couple of years ago. It was disappointing that the mainstream art magazines opted to ignore the important Fritz Scholder exhibition which remains on view at NMAI in Washington, D.C. Where is the feature article in Art in America? A professional PR firm was hired to promote the two city project with scant results. Why does contemporary Native American art continue to be ignored with impunity?

We are waiting for an artist to emerge with real star quality and visibility. There needs to be the next generation that builds on what was accomplished by Jaune Quick to See Smith, James Luna, Jimmie Durham, Kay Walking Stick, George Longfish, or Fritz Scholder. This is already happening in Canada more than in the US. But there is just as likely a resistance to this development. Rather than move forward into the cultural mainstream there are many Native leaders who feel it is important to pull back and retrench. To avoid the corruptions of mainstream America and return to traditional life. Probably it is all true.

There needs to be progress on all points of the compass. Perhaps you can't have one without the other. As Smith points out debate and contention, diversity and adversity are a part of Native culture. There are historic issues of tribal differences. Like Costner's absurdly insulting substitution of Sioux for Comanche. Nobody seemed to notice or care as he walked away with all those Oscars for a feel good film.

Precisely because there are so many conflicts and challenges an attempt to understand Native American history and culture is essential to the American Experience. There is horrendous damage, broken treaties, theft of land and natural resources, systematic government strategies to destroy languages and culture, genocide to be dealt with. But Smith ironically states that he is not interested in pursuing a guilt trip. His book sets forth there are issues of dealing with the here and now. There is joy and pain in his writing as well as uncanny wisdom. It is a book of essays that deserves to be widely read. It does indeed convey that everything you know about Indians is wrong. Fine. Got that. Cool. Now what?