Ai Weiwei: Never Sorry at BIFF

For China Ai Weiwei or the Highway

By: Charles Giuliano - Jun 04, 2012

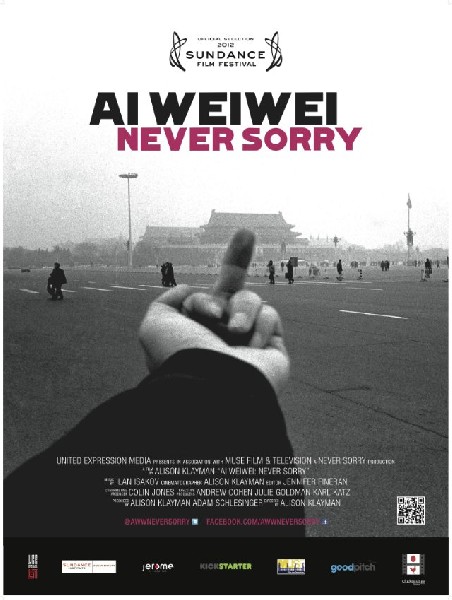

Ai Weiwei: Never Sorry

Director: Allison Klayman

Producers: Andrew Cohen, Julie Goldman, Karl Katz, Allison Klayman, Adam Schlesinger

91 Minutes

Berkshire International Film Festival

As the riveting documentary by Allison Klayman, Ai Weiwei: Never Sorry, made compellingly clear he is the most influential and dangerous of China’s artists and dissidents.

When he last attempted to travel, in 2011, the artist disappeared for 81 days of interrogation. When he was released in June, uncharacteristically with apologies, he declined comment stating that he was out on “bail.” Silence, it seems, was a condition of his release. Later violated as he resumed to communicate by Twitter and Skype an essence of his persona and art practice.

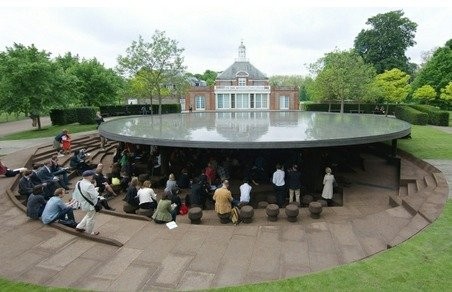

It was by this means that he worked to create a project which opened last week at the Serpentine Gallery in London. There is ongoing global concern that Weiwei is unable to travel.

The Serpentine Gallery in London's Hyde Park unveiled their annual pavilion at a press conference last Thursday. Though architects Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron were present to elaborate on the design and ideas behind the structure, collaborator Weiwei was not. The team, who previously worked on the Beijing National Stadium for the 2008 Olympics, had to conduct their meetings over Skype.

Their unique “Birdsnest” design brought the artist spontaneous global recognition and admiration. It might easily have been parlayed into a lucrative career pursuing other, epic scaled commissions. Compared to which, the Serpentine project with Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron is revealingly modest in scale and ambition.

The artist fouled his own “Birdsnest” with remarks critical of the government’s treatment of its citizens and efforts to maximize the propaganda potential of the Olympics. Weiwei was openly critical refusing to put on a “happy face” or be photographed next to his creation.

Typically, freedom of expression and dissent, using the platform of world media for the Olympic Games, was more important to him than an opportunity to shine in the spotlight.

Weiwei was born 18 May 1957, the son of the poet Ai Qing. His father was denounced during the Cultural Revolution and in 1958 sent to a labor camp in Xinjiang with his wife, Gao Ying. Weiwei was one year old at the time and lived in Shihezi for 16 years. In 1975 the family returned to Beijing.

Ironically, his father was a member of the communist party who had been in prison for a number of years under Chiang Kai-shek. At the risk of prison or death Qing traveled across many provinces to join Mao’s army then fighting Japan. He was later a literary advisor to Mao. Qing fell out of favor when a brief prose work was viewed as subversive. The film conveyed that his father made a number of attempts at suicide.

To outside observers China has made great progress since the era of Mao and the discrediting of the Gang of Four which succeeded him. When we visited Shanghai a number of years ago I expected to see people in those famous, generic Mao suits and caps. The city we encountered, one of the fastest growing in the world, was so Western that I asked myself, driving past McDonalds and Kentucky Fried Chicken, The Gap and other American signifiers, “Are we in China or Chinatown?”

One may argue that China has made so much social and political progress that it is now possible to have an Ai Weiwei. From his point of view, however, that’s not enough until there is complete democracy and freedom of expression. Asked if he is afraid Weiwei responds, yes, but even more afraid of what happens when nobody dissents.

As the film reveals, in an ongoing game of cat and mouse, he and his associates confront, photograph, record and Tweet those who have them under constant surveillance. They video him and he videos them. It is amusing, Weiwei is a man with an infectious sense of humor and irony, but also terribly brave and terrifying.

In a well documented incident he was visited in the middle of the night by local police who assaulted him. He was bashed in the head resulting in brain damage requiring surgery that almost cost his life. Typically, Weiwei documented all aspects of the assault and recovery.

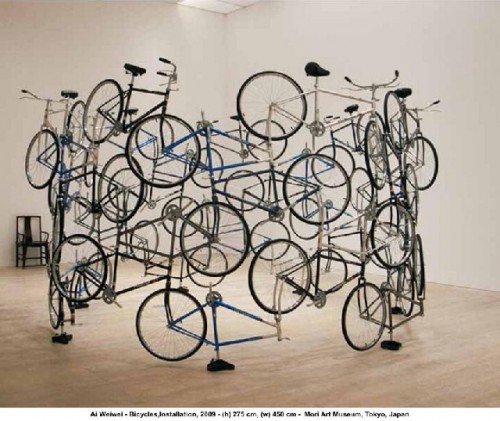

After art education in China, from 1981 to 1993, he lived in the United States, mostly in New York, creating conceptual art by altering readymade objects. He studied at Parsons School of Design and at the Art Students League of New York. He became fascinated by Atlantic City casinos.

In 1993, Ai returned to China after his father became ill. He helped establish the experimental artists' Beijing East Village and published a series of three books about this new generation of artists: Black Cover Book (1994), White Cover Book (1995), and Gray Cover Book (1997). They were distributed and sold clandestinely.

From his residence in New York Weiwei became fluent in English and also absorbed the avant-garde of that era particularly conceptual, multi media, installation, and performance art. For his first New York gallery exhibition he deconstructed shoes. It was early during the awareness of AIDS. He created a rain coat with an external, attached condom in the vicinity of the wearer’s penis.

Perhaps from pop artists like Andy Warhol and Robert Rauschenberg, or neo dada composer John Cage, he took a cue from Marshall McLuhan that “The medium is the message.” The camera and tape recorder, later internet, became as much a part him as the five senses, arms and legs.

Only on the rarest occasions does he refuse an interview or photo op. It becomes annoying that he always is asked the same questions. But there is no indication of any value judgment of those who interact with him. A reporter, for example, seemed uncertain and apologetic for asking about his private life. Particularly regarding an out of wedlock son and how that impacted the relationship with his wife. The artist was amazingly candid taking full responsibility for the child who lives with his mother. He stated not being proud of the circumstances but things happen and you deal with it.

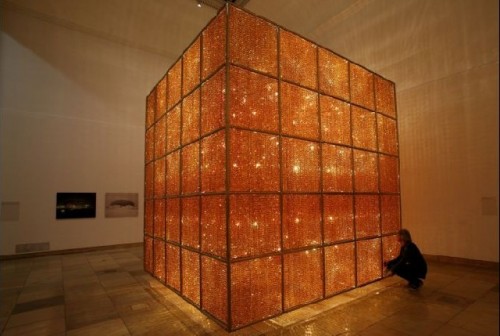

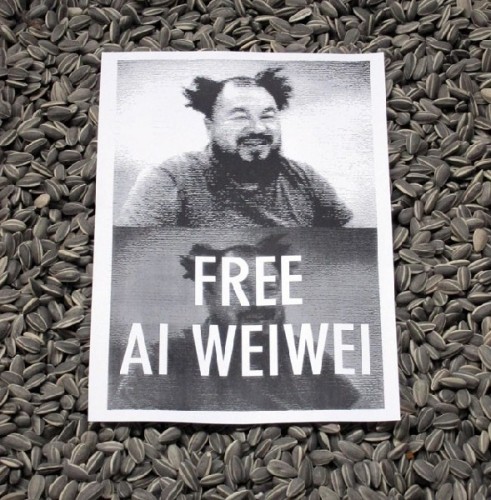

The sequences of Weiwei and his son are just wonderful. There is such tenderness and love in their interaction. One of the most stunning moments in Klayman’s film shows them together walking over millions of hand made, ersatz, sunflower seeds in the vast Turbine Hall of Tate Modern in London.

The artist encouraged museum visitors to walk over his field of seeds. But the resultant porcelain dust became hazzardous to breathe and the museum halted that activity.

A mantra of the artist is truth and honesty. There are responsibilities that come with actions. In a harrowing incident, which perhaps led to his incarceration, he confronted the officer who had attacked him. In an act of stunning bravery and defiance he ripped off the sunglasses of the policeman and accused him as his attacker. There was pandemonium as the incident was recorded by the artist and his followers as well as undercover police that converged on them.

In a later scene he was asked if it was an act of revenge? No, he responded, it was about teaching a lesson of taking responsibility for their actions.

That’s pretty incredible. Just think about it. Standing up to a totalitarian government and teaching them a lesson about moral responsibility. And, unlike many other dissidents, living to tell the tale. But at incredible personal risk. There is a poignant scene with his mother who expresses concerns for his safety. He responds to her philosophically about the inevitable.

One of his most famous moral instructions was outing the government which refused to provide a list of the some 5,000 school children killed during a 2008 earthquake. While other buildings endured the schools, scandalously created in the cheapest possible manner with “tofu walls,” collapsed. It represented a stunning indictment of corruption.

Using his then popular website the artist inspired numerous volunteers to track down the names of the children. These he later posted on his website leading authorities to shut it down.

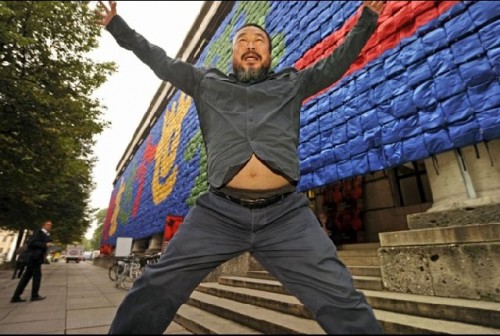

For a German exhibition he used an enormous horizontal wall festooned with different colored back packs inspired by those found in the wreckage. Weiwei spelled out a comment from the parents of one of the children “She lived happily in this world for seven years.”

In order to create a single class society Mao decreed that it was necessary to destroy China’s past, its symbols and institutions, crush all dissent, reeducate capitalists, intellectuals, elite professionals and artists in order to create a new China. In a fanatical Maoist frenzy many monuments and priceless works of art were destroyed.

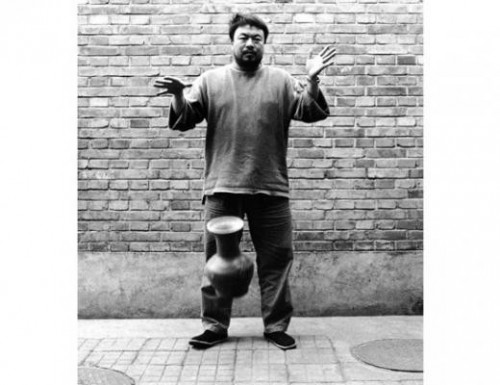

Ironically, creating and destroying are essential to Weiwei's critical process. In one famous sequence of photographs the artist drops and destroys a rare Han Dynasty vase. Of course there are precedents for this in the dada tradition. One recalls Raushenberg meticulously erasing a drawing given to him by de Kooning.

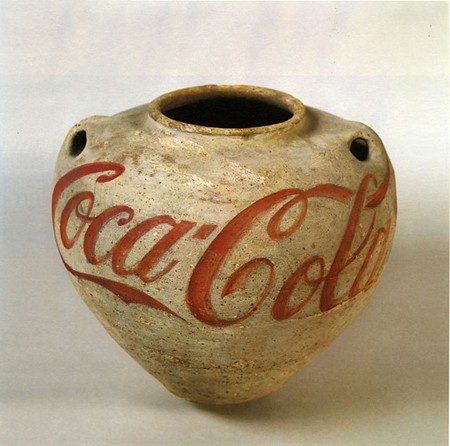

There is a series of works by Weiwei where he has glazed over Neolithic Chinese ceramics with bright colors. On some of them he has painted the logo of Coca Cola. An interviewer asks if he has destroyed these treasured objects? He doesn’t think so. An old work now has new life. It is a metaphor for how we destroy the past to make way for the future. There is something Darwinian about this approach. Unlike Mao, for Weiwei it is not Cultural Revolution, but, arguably, Cultural Evolution.

Not that I am suggesting that we storm the world’s museums and smash its treasures. Which, by the way, is what the Taliban did in Afghanistan when it used dynamite to destroy ancient Buddhist monuments carved into the sides of mountains. It was not exactly a conceptual art piece.

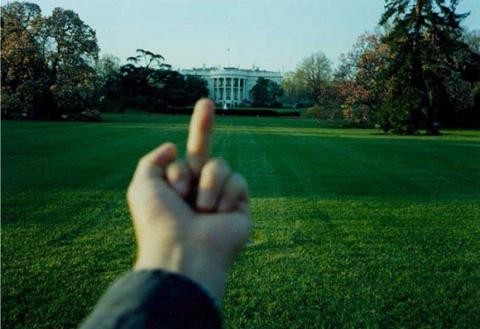

The Weiwei we meet in the wonderful film about him is a fat, jolly, full of life, ranting and raving humanist. Nothing is sacred including himself. He likes to give the finger to our jingoistic monuments. In his Studies of Perspective (1995-2003) we see the artist's outstretched middle finger in front of views of Tiananmen Square, The White House, The Eiffel Tower, The Mona Lisa.

Ironically, the tug of war with Chinese authority resulted in the government sponsored destruction of the vast studio he designed and constructed. Typically, we saw him on site in a hard hat recording the demolition and tweeting it globally. Prior to the demolition Wewei hosted a feast of boiled river crabs.

When asked about the destruction of his studio he speculated about what’s next. Not long after he was detained.

In June 2011, the Beijing Local Taxation Bureau demanded a total of over 12 million yuan (US $1.85 million) from Beijing Fake Cultural Development Ltd in unpaid taxes and fines. Since then millions in contributions from Chinese supporters have poured in. His assistants are tracking and documenting the staggering number of donations.

In the infectious and provocative spirit of the artist, and the struggle for freedom of expression that he represents, let us end with a poetic thought.

Ai Weiwei go fuck yourself.