Carl Belz Three

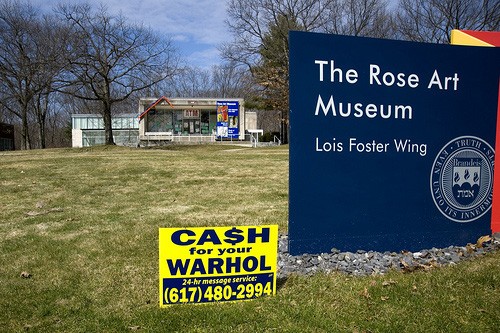

Legacy and Future of the Rose Art Museum

By: Carl Belz and Charles Giuliano - Jun 08, 2011

Charles Giuliano Let’s discuss the issue of value. I mentioned that when we looked through the Gevirtz-Mnuchin folder you estimated the work of that collection at some $13 million and that was perhaps twenty years ago.

Perhaps it’s crass to talk in terms of money. But that appears to be precisely how the collection was viewed by Yehuda Reinharz. The works of art represented an asset that could be liquidated and converted to cash.

When individuals give major works to a museum they assume that their generosity builds on a legacy that will grow and enrich the institution for generations to come. It is an investment for the future. Of course time and taste is unpredictable. Some works increase in value and critical reputation while others do not.

The reputations of curators and museum directors depend on their track record for exhibitions and acquisitions. In that sense Sam Hunter proved to be exceptional. The majority of what he acquired has greatly increased in value. Obviously not each and every work. But a good percentage of what he selected has been in demand for many museum exhibitions. It was always gratifying, as an alumnus, to see works from the Rose in museum retrospectives for Warhol, Lichtenstein, Rauschenberg and Rosenquist to mention but a few.

Having works to loan also provides the kind of quid pro quo bargaining chips to borrow for Rose exhibitions. Yes the Rose, as you put it, was a small museum in Waltham, but also a very special place.

In these difficult economic times the Rose was among high profile museum collections to be targeted as collateral to pay down debt or avoid bankruptcy. The responses of alumni have been divisive. Many view the loss of the Rose as a more acceptable option than reducing or eliminating other programs. The arts, as usual, are the first to go.

Consider, however, should Trinity College in Dublin fall on hard times. Imagine if the trustees opted to sell the Book of Kells. Or Harvard decided to sell off and close down the Fogg Art Museum.

Of course such possibilities are speculative.

Was the decision of Brandeis regarding the Rose any less shocking and hurtful?

It is logical to assume that the value and aesthetic importance of the Rose will only increase with time? After much debate Reinharz proposed selling a selection of the most valuable works.

This leads to a double question. First, in your opinion, what are the essential works in the Rose collection? The works of art that define the Rose. What are your responses to the attacks on the Rose as a former director? During the hard times on your watch you have previously disclosed to me that the Rose was a tempting treasure trove for the President and Trustees.

Can you comment on the restraint of former President Handlin for keeping her hands off the Rose? And the decision of Reinharz, under a later administration, to attempt to close the Rose as an independent museum, and sell the collection.

That has still not happened but the fate of the Rose is yet to be resolved.

Carl Belz I recall standing with Evelyn Handler on the front steps of the museum on a sunny afternoon while a reception was taking place at the Rose, and she told me I would not like what she was going to do with "my" museum. I didn't ask her what she meant, I just responded by telling her not to worry about it, we'd be all right. Indirectly, I learned that she was planning to propose to the Board of Trustees that the university sell large portions of the collection, and I was subsequently told that Hank Foster--I can't remember if he was chairman at the time or just a member of the board--had mobilized the trustees to oppose any such move, and that's the last I heard of it.

What interests me about this tale is (1) The collection was viewed simply as a commodity by the president, the president of a supposedly first-rate liberal arts university; so how's that for leadership? You say you want to talk about "value"? Educational value? Esthetic value? Historic value? All of the above? Well, what it comes down to here is monetary value, pure and simple. End of Discussion. And (2) This was going on without any input whatsoever from the director of the museum or any other arts professionals. I will leave it to you to draw conclusions about what that means vis a vis the president's regard for the stature of those entrusted "to collect, preserve and make available to the public" the university's art collection.

Regarding President Reinharz, well, I wasn't there, but my impression was this: (1) The collection was viewed simply as a commodity by the president, blah, blah, blah. And (2) This was going on without an input, blah, blah, blah.

There's an old saying, how does it go? From the French, I believe. Something about things changing and yet not changing, changing but staying the same. I can't remember, but anyway, it all turned out not to be the same when Reinharz said it as when Handler said it, because it didn't just go away the second time around. And it hasn't gone away since 2009. And it looks like many moons will wax and wane before it ever goes away. And can you imagine how that founding generation of New York Jewish intellectuals, the generation we were talking about earlier in our conversation, would feel about that legacy?

CG During my many visits with you there were comments about Team Rose. In particular the curator Susan Stoops, who is now curator of contemporary art at the Worcester Art Museum, and the artist preparator Roger Kizik. As I know from my experience of running a university exhibition program having a curator with another point of view, to spell you in organizing projects, and someone reliable to install shows is essential. At Suffolk University that person for me, combining both functions, was James Manning.

Earlier on you described reinstalling the permanent collection on a regular basis. Between installations Kizik spent his time at the museum creating and carving unique frames. The geometric patterns for a painting by Marsden Hartley would be one such example. It was an in-house manner of enhancing the collection.

From my curatorial experience, there is also the matter of dealing with the demands and ego of artists. Most were a delight to work with while others were not. The experience can leave a sour taste. Of course we make every effort to satisfy the vision of the artist and how best to present the work. But there were times when the expectations are just over the top. The ultimate example of that would be Christoph Buchel who brought Mass MoCA to a standstill with a lawsuit that threatened to ruin the museum. During the opening of an exhibition, I curated for the Fitchburg Art Museum an artist insisted that I rehang her painting. An artist ruined the Christmas holiday wrangling about my essay for the catalogue that he published. I had no money for a publication, but he did. To my regret, in exasperation, I gave up, and he rewrote my essay about him, made up a quote by me, and put my name to it. I attended the opening but have never spoken with him since then.

For one of your major exhibitions, I understand that Dorothea Rockburn was not satisfied with the installation. The entire show was rehung and shifted a few inches. I am sure Kizik recalls that experience more vividly than you do.

Can you share with us the pleasures and frustrations of working with artists over many years? In particular who did you bond with in the process of developing projects? Looking back, would it be possible to define your taste and point of view? Is it fair to say that you had a particular focus on aspects of abstract painting? Can you expand on the diversity that Stoops brought to the program? And the unique skills that Kizik provided?

CB Did I favor abstract art?

Abstraction was always my first love--modernist abstraction--but I realized early on as a museum director/curator that I couldn't limit our program to abstraction alone. The program had to embrace a much broader view of contemporary art, including a much broader view of modernism itself. When we did our first Patrons and Friends exhibition, "Alex Katz in the Seventies," I wasn't altogether confident about the prospect of writing about the work, wasn't sure I could do it justice, so we got Roberta Smith to write the catalog essay. She did a terrific job--taught me a lot about ways of seeing Alex's work--but I then determined that, henceforth, I had to carry the ball and fully curate those exhibitions. In other words, I had no intention of being an administrator/development-type director who would hire on guest curators. I viewed my job as director/curator. Just as Bill Seitz and Sam Hunter had before me. Overall, my record probably inclines toward abstraction, but above all I think it demonstrates a comprehensive--as opposed to a narrow or reductive--vision of modernism in particular and of contemporary art in general.

Did I run into difficult artists?

We always got along well with the artists we worked with. Sure, some were more demanding than others, and preparator Roger Kizik and I would occasionally balk when one of them wanted him to lower a picture by an inch or asked me to change a word in the catalog essay I'd written. But we didn't fret and stew about that, we figured it was all in a day's work. We were there to serve the artists. Their efforts made it possible for us to do what we did. Our job was to work with them toward the goal of allowing their art to show all that it had to offer--to sing to its fullest capacity. It may have been old-fashioned, but our operating premise was that the exhibition was about them, not us.

What did preparator Roger Kizik and curator Susan Stoops bring to the program?

Roger and Susan were my colleagues of longest standing during my tenure as director--Roger having started in the mid-1970s and Susan a little under a decade after that. As preparator, Roger installed exhibitions and managed storage of the collection, built pedestals and crates, constructed and painted temporary walls, all the usual stuff. But he did a lot more than that. He single-handedly conducted our office loan program, a public relations activity whereby members of the faculty and administration could borrow works from the collection to hang in their campus offices; we jokingly called it "The Rose Art Decorating Service" and it was a bit of a headache--"No, you can't have the Jasper Johns, it's restricted!"--but Roger had the patience to make it work. He occasionally carved frames for pictures in the collection, which were super inventions, works of art in themselves. He dreamed up and executed signage for the 12 foot square wall inside the front door that greeted visitors for each temporary exhibition. He regularly contributed ideas for the design of our exhibitions, many of which I received credit for; among them was the Todd McKie and Judy Kensley McKie exhibition, which remains etched in my memory as one of the best ever. And, finally, he contributed immeasurably to the museum staff's ongoing art discourse--the one that took place in the office, or the shop, or in one of the galleries when a show was going up or coming down or a new acquisition had arrived--with an eye and voice as acutely sensitive to the workings of works of art as any I've been privileged to encounter.

To put it succinctly, Susan Stoops professionalized the position of curator at the Rose. The position didn't exist when I became director (its earlier equivalent, the assistant director position, had been eliminated entirely by the time I arrived). It evolved out of the staff assistant position (what was once called a secretary), for which I was able to hire overqualified people, underpaying them in exchange for the opportunity of assisting me on exhibitions. That person gradually assumed increased responsibility, which translated into curating an exhibition of his or her choosing instead of mostly following my lead. So the outline for a full curatorial slot existed when Susan stepped into the position--she'd started as an overqualified registrar, so she knew the operation inside and out--in the mid-80s. Her challenge was to bring it fully to life.

Which she did--I mean, did she ever! For the next 15 years we made a great team, complementing one another, teaching and learning from one another. She valued the area artists community as much as I did, and we equally enjoyed doing studio visits that annually led to exhibitions we together curated. While she put together a series of solo shows--Eva Hesse, Kiki Smith, Dorothea Rockburne--which was the format I personally preferred, she also organized thematic exhibitions in which she invariably included area artists along with artists who enjoyed regional or national reputations--"The Contemporary Drawing: Existence, Passage, and the Dream" (1991), comes immediately to mind. And by way of contemporary art history, she mounted "More Than Minimal: Feminism and Abstraction in the 70s", which included the cluster of major acquisitions that I mentioned earlier. To many of these projects she brought a feminist perspective--which was absent from my own background and which I learned largely through her--which contributed significantly in the ongoing shaping of the museum's program and collections. She contributed enormously to the building of our photography collection, a project that began at just about square one, she guided production of the 25th Rose Art Museum Anniversary Collection Catalog, a model of scholarship. The museum remains deeply indebted to her, as do I.