On This Ground: Being and Belonging in America

Revisionist Installation at Peabody Essex Museum

By: Charles Giuliano - Jun 17, 2022

On This Ground: Being and Belonging in America, curated by Karen Kramer and Sarah Chasse at the Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, ongoing.

In 2019 my wife Astrid and I visited museums in Montreal, Ottawa, and Toronto. They were very different from how we remembered them. In addition to numerous special exhibitions, the work of First Nation artists and artisans, both traditional and contemporary, had been fully integrated into the institutions.

That movement toward unification was initiated in 2017 by Matthew Teitelbaum, then the director of the Art Gallery of Ontario and currently the director of the Museum of Fine Arts Boston, on the occasion of Canada’s 150th anniversary.

When I asked him about that decision, Teitelbaum told me that the intent was to show all of Canadian art, which propelled the hiring, for the first time, of an indigenous curator of Canadian art. In contrast, when Malcolm Rogers oversaw the creation of a new American Wing at the MFA, the representation of Native American art was (literally) confined to a few artifacts in the last gallery.

That attitude will change slowly at the MFA, which has shown little to no interest or commitment to this work. Recently, the museum acquired a major work by the leading artist Jaune Quick-to-See Smith. She is slated for an upcoming retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art. Previously, the Whitney has exhibited Jimmie Durham, whose native heritage is debated.

The Peabody Essex Museum has long collected Native American material and is now doing so intensively. In that regard it is an outlier. Contemporary Native American artists have been egregiously neglected by the mainstream American art world — we lag far behind Canada.

The PEM has just reinstalled its American collection, which runs from the Colonial era to the present, and it is an ambitious, intriguing, but problematic exhibition. On This Ground: Being and Belonging in America has been handsomely installed by curators Karen Kramer and Sarah Chasse. They had a committee of Indigenous advisors and scholars who contributed to the signage and elaborate texts that deconstruct and contextualize the works on display.

The result is an illustrated revision of American art, history, and culture. PEM has many fine works on view here, but this curatorial effort is not intended to celebrate the institution’s familiar masterpieces. On This Ground reflects an antihierarchical approach, a trend in how art history is taught. Powerpoint presentations are replacing slide shows. Canonical texts by H.W. Janson and Helen Gardner have been revised and replaced.

In an iconic 1983 article “The Imaginary Orient,” Linda Nochlin explained how this heuristic change should be viewed:

Yet it seems to me that both positions — on the one hand, that which sees the exclusion of nineteenth-century academic art from the sacred precincts as the result of some dealer’s machinations or an avant-garde cabal; and on the other, that which see the wish to include them as a revisionist plot to weaken the quality of high art as a category — are wrong. Both are based on the notion of art history as a positive rather than as a critical discipline.

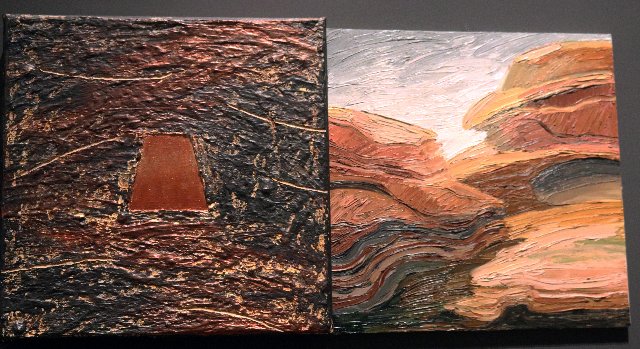

Not surprisingly the most impactful aspect of this installation features work by leading Native American artists: Kay Walking Stick, Alan Michelson, Will Wilson, and Marie Watt. If you have been paying attention for the past decade they are readily familiar.

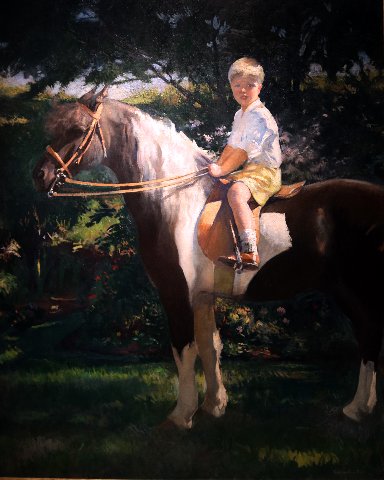

Stridently, at times amusingly, the Colonial-through-19th-century portraits, of which PEM owns outstanding examples, are set up as straw men for revisionist talking points. One might add, rightly so; it is hard not to agree with the smack-downs on the show’s labels. These good citizens made fortunes in blood money. The portraits of children by Boston Impressionists Frank W. Benson, such as his “Portrait of Jane Shattuck,” and Edmund Charles Tarbell’s “Edmund and His Pony Peanut” come off today as hilariously sentimental signifiers of rich white privilege. It’s a scandal that the MFA collected their works in depth while ignoring the Jewish Boston Expressionists. Still, there is a question worth asking: in terms of art history, does that mean we can no longer admire the skill of Colonial masters such as John Smibert, Robert Feke, Joseph Blackburn, and John Singleton Copley?

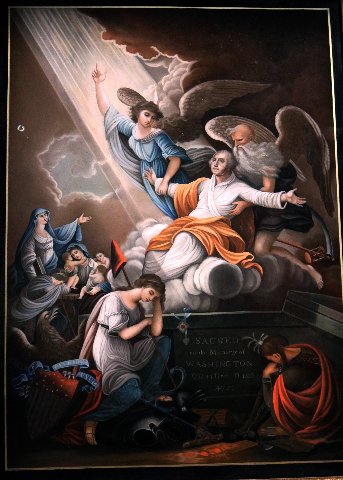

It was particularly delicious to see George Washington get his comeuppance. There is an unintentionally humorous painting of the apotheosis of the saintly president painted in China (1802-05) after an engraving. Juxtaposed with that picture of the beloved founding father is a gob smack from Alan Michelson. A video stream of images documenting Washington’s racist treatment of Natives, who were regarded as noncitizens in our democracy, is projected onto a bust of our first president by Jean-Antoine Houdon. The tribes fought along with Washington during the French & Indian War, but after the Revolution he refused to meet with them and honor treaties. Let us not forget that Washington owned slaves, as did our other presidents, except Adams, father and son, up until Lincoln.

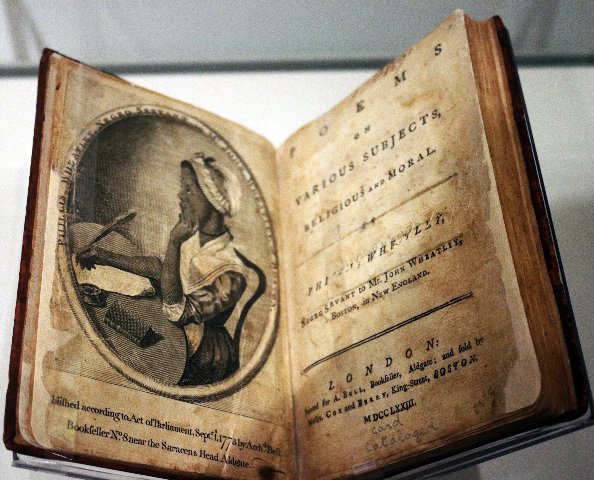

If you look carefully around the exhibition there are some wonderful discoveries. It was thrilling to see a copy of poems by Phillis Wheatley Pearce (1753-1784), a Boston household slave. A 19th-century Wampanoag nation eel trap is an eyeful.

One of the installation’s themes is to critique America’s idealized romance with Indians with the reality of Native Americans. In 1906, J.P. Morgan provided photographer Edward S. Curtis with $75,000 to produce a series on Native Americans. The project extended over 20 years. The images were staged and sanitized. A selection of his images is contrasted with a series by Navajo artist Will Wilson, who photographs neighbors in their homes wearing clothing of their choosing.

Since the PEM is located in Salem, it is not surprising that we learn about the city’s infamous witch trials. There is a corny painting by hack illustrator Tompkins Harrison Matteson (1813–1884), The Trial of George Jacobs, August 5, 1692, 1855. In this case, the curators have turned a blind eye to matters of taste and quality. Apparently they are drawing on Nochlin’s thesis: it’s OK to show bad art — if it makes a critical point. This is not the only such lapse of responsibility in this exhibition, which left me with much to think about. In the end, it felt more like I had been given a demythifying history lesson rather than an enriching aesthetic experience. What is the point of dumbing down the canon for the sake of educating the general public?

Reposted courtesy of Arts Fuse.