Temporary Structures

Architecture As Minimalist Functional Sculptures

By: Mark Favermann - Jun 27, 2011

As an incubator of architectural ideas, individual houses have traditionally been the projects that most younger architects and small firms created to make a personal or unique visual statement. Recently, however, the notion of the temporary, nomadic structure has been the dynamic impetus that has been seen as an elegantly less (in structure size and budget) rather than more design challenge. Larger, more established firms have joined in this creative process as well.

The line between sculptural form and functional architecture is sometimes hard to discern. The visual excitement and physical tension is in the balance between the use of materials, scale and shapes. In the last few years, a noticeable and sometimes noteworthy new architectural trend has arisen, finely designed temporary structures. Sometimes sculptors create temporary architectural structures as well. The most famous institutional temporary structures project is at London's Serpentine Gallery Pavilion.

However, other notable stand alone temporary projects have recently been built. In Winnipeg, a city of 600,000 residents located on the Canadian prairie and the coldest city of its size outside of Siberia, winter can last six months. Patkau Architects of Vancouver, Canada looked at the weather and natural environment as a creative opportunity. The careful result was a sculptural series of beautiful functional elements.

The Red and the Assiniboine Rivers meet in city center, and when plowed of snow, skating trails many miles long are created. With temperatures that drop to minus 30 and below for long periods of time and high winds, there is a need to find shelter. This in turn greatly enhances the ability to use the river skating trails. A program was developed to sponsor the design and construction of temporary shelters located along the skating trails, the Winnipeg Skating Shelters.

Patkau Architects' proposal consisted of a cluster of intimate shelters that could accommodate only a few people at a time. They are assembled into a small grouping (referred to by Patkau as a ‘herd’, or ‘school’, or ’flock’, or ‘flotilla’) to form a collective that defies a single interpretation. Standing with their backs to the wind, these asymetrical structures huddle together shielding each other from the elements.

Each shelter is formed of thin, flexible plywood which is given both structure and spatial character through bending and deformation. Skins, made of 2 layers of 3/16th inch thick flexible plywood, are cut in patterns and attached to a timber armature which consists of a triangular base, and wedge shaped spine and ridge members. Thoughtfully, the ridge is a line engineered to negate the gravity loads of snow. Stress points were relieved by a series of cuts and openings.

These temporary structures are delicate and ‘alive’ functional sculptures. They move gently in the wind, creaking and swaying to and fro. They visually float on the surface of the frozen river. Snow does not easily adhere to their surfaces. Here architecture becomes sculpture underscoring the ferocity and cold beauty of winter on the Canadian prairies.

It is a damn shame that Patkau Architects and other creative and innovative Canadian firms were not enlisted to assist with the design of the Vancouver 2010 Winter Olympics. These highly watched games were visually unappealing and quite mediocre in concept, lazy design and faulty structural implementation. A major, major design opportunity was lost in Vancouver. These Winnipeg Skating Shelters demonstrate that special and even spectacular temporary structures could have been created by talented Canadian firms.

Heather Peak and Ivan Morison are two Wales-based environmental artists who have created a number of temporary structures. Their work strives to interrupt or intervene in the status quo. The way they do this varies, from creating sculptural installations in everyday spaces or at institutions to building huge architectural objects that also function as temporary meeting places. The Morisons created The Black Cloud in 2009.

Over the past ten years, they have exhibited internationally, including as the representatives of Wales in 2007 at the 52nd Venice Bienniale. Heather and Ivan Morison also own their own forest in North Wales. They are turning the forest into an arboretum from which they eventually will take wood to make their artwork.

Looking like a giant black insect, a monstrous sea creature or a creepy space invader, The Black Cloud was an imposing wooden pavilion inspired by the Amazonian dwellings of the Yanomamo tribe. Constructed using the Amish principles of communal participation, it was protected from the elements by an ancient Japanese scorching technique.

The paneled structure was further overlaid with the artists’ own rather dark narrative. The Morisons’ saw it as a shelter for a future apocalyptic world scorched black by an unrelenting sun. Hybrid in style, contexturally The Black Cloud reflects many of the artists' own references to the prophetic visions of twentieth century science fiction writers, the urgent contemporary concerns of the Arts & Ecology movement and the real world application of collectivist ideals within controlled environments.

The Black Cloud’s hybrid nature also extends to its function. It was both a sculpture and a designated platform for public events. The structure itself, the focal point of communal art activity, was ultimately completed in just over twelve hours. The "builders" took part in a communal experience similar to the Shakers raising a barn. The Black Cloud was activated across summer and into autumn by other participatory events instigated by the Morisons.

Despite its monumental nature, the sculpture was always intended to reside for just four months in a corner of Victoria Park in Bristol, England. It was then quite carefully removed piece by piece, so that only faint marks on the grass indicate that anything was ever there. Here once was sculpture that was also architecture.

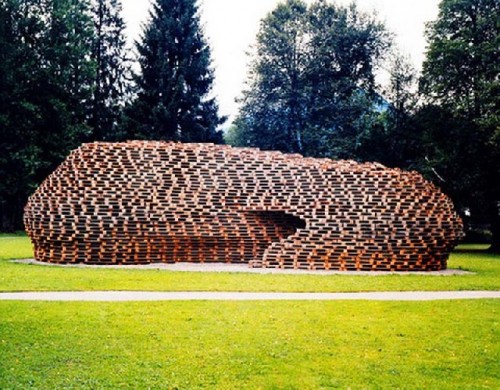

In 2005, German architect Matthias Loebermann created Pallet Pavillion (Palettenvillon), a crunchy structure made entirely of stacked pallets. Very green, the project was designed to be disassembled and easily reused in other ways, with minimal waste. The structure showcases designer’s ability to create a complex structural “shell” from an element as simple as a common wooden shipping pallet. The sculptural composition is made up of 1,300 pallets. The entire structure is secured by straps that are commonly used to keep the pallets together on trucks.

At night dramatic effects are caused with light and shadow created by the gaps left within and between the pallets. The dimensions of the structure are 6m by 8m by 18m. This is one of several elegant temporary solutions that Matthias Loebermann has created with homely materials.

In 2009, architect Zaha Hadid created a temporary pavilion to celebrate the 100th anniversary of pioneer urban planner Daniel Burnham's Plan of Chicago. Reviewing the original plan's drawings, Hadid noticed how the city's diagonal streets opened up the rigid street grid. The design for the Burnham Pavilion incorporated that diagonal, as the structural ribs and openings in the roof run parallel to an imaginary extension of Burnham's street pattern. The result was Hadid's sinuous, very organic almost biological-looking pavilion.

Over 7,000 pieces of aluminum, with no two alike, were individually bent and welded together to create the pavilion's curvilinear form. Thousands of yards of fabric were custom tailored and fit onto the interior and exterior aluminum-tube structure. The ridges of the aluminum were deliberately expressed through the external skin.

While light and shadow changed as the skylights cast shadows on the curving interior walls during the day, in the evening a film was projected onto the fluid fabric interior from different points inside the pavilion, creating a fully immersive effect. The pavilion's materials were completely recyclable, and were dismantled and reinstalled in New York City after the Burnham Centennial.

Temporary architectural commissions are an ongoing ephemeral structures program specially created by internationally acclaimed architects and designers at the Serpentine Gallery. The unique series presents the work of an international architect or design team who has not completed a building in England at the time of the Serpentine Gallery’s invitation.

Many star architects, artists and designers have participated over the last decade or so including Jean Nouvel, 2010; Kazuyo Sejima and Ryue Nishizawa, SANAA, 2009; Frank Gehry, 2008; Olafur Eliasson and Kjetil Thorsen, 2007; Rem Koolhaas and Cecil Balmond, with Arup, 2006; Álvaro Siza and Eduardo Souto de Moura with Cecil Balmond, Arup, 2005; MVRDV with Arup, 2004 (un-realised); Oscar Niemeyer, 2003; Toyo Ito with Arup, 2002; Daniel Libeskind with Arup, 2001; and Zaha Hadid, 2000.

This summer Peter Zumthor’s Serpentine Gallery Pavilion will operate as a public space and as a compelling venue for Park Nights, the Gallery’s high-profile program of public talks and events. In the Fall, as with every other yearly Serpentine commission, the structure will be taken down, the materials will be donated to worthy organization or institution and the site emptied and refurbished for next year's commission.

With the exception of Zaha Hadid's Burnham Pavilion, all of the previous examples have been created and built outside of the United States. With all the potential creative opportunities of temporary pavilions, wouldn't it be wonderful to have a series of impermanent structures developed for the Appalachian Mountain Trail, Mount Greylock, the Charles River Basin, the Cape Cod Canal and scores of others?