Venice Biennale 2009

Bruce Nauman Wins the Golden Lion

By: Ben Klein - Jun 28, 2009

This year's Venice Biennale is many things, like every installment of what is probably the world's most important art show. Overall it's a spectacular, wonderful experience.. Certainly there are standouts; both sublime and miserable. The show is vast, indeed and with much so good or at least credible, there's no reason to dwell on the many small failures and few larger ones. One aspect in particular about the Biennale stands out above the whole the work of Bruce Nauman.

This year Nauman accepted an oft-extended invitation to represent the U.S., and the results are spectacular. The experience as a whole of the Biennale seems colored by the presence of Nauman's work, especially because there are two more exhibits of his work around town, all in close proximity. What's on view at the American pavilion is classic Nauman. To name a few of the works, there are spouting-head fountain sculptures, cast-hand sculptures, neon pieces, including the well-known "The true artist helps the world by revealing mystic truths." The work in neon is installed in a window of the building, whose frieze is itself adorned with more of his punning, wordplay light reliefs. But the kicker is that, elsewhere, he's debuted a new piece, in two locations (and languages); and even though, technically not part of the Biennale, the piece, titled "Days/Giorno", acts as an apt synecdoche for the Biennale.

With one instance in English, and one in Italian, essentially the piece consists of a long room, with a corridor of installed panels at head height dividing the width of the space into thirds, with the main action taking place in the middle third where the sound is primarily directed. The panels, made of a flat, white material and each equipped behind with a speaker and its electronic gear, emit the sound component that makes up the content of the work. Each (and there are seven per side) speaks with a different person's voice: people of both sexes, and all ages, in the most distinct and markedly personal of voices intone, out of "order", the days of the week.

Just to be wrapped in the sound of it all, is frankly astonishing. It's difficult to imagine the effect of it, from simply hearing a description. One gets the impression of the greatest clarity and intellectual decisiveness at the same time as a beautiful, but deeply unnerving sense of what Schizophrenia may be like. Nauman, almost alone among artists working today is, at his best, a totally accessible, universal artist, and the most accomplished of conceptual mandarins. He is also one of the few who is truly haunting, and evocative in expressive terms, while maintaining the highest intellectual standards. Nauman is the presenter of some of our finest challenges.

The national pavilions are a mixed bag; some, like Canada's, where Barbara Fischer has curated a tight, elegant show of the work of Mark Lewis, are good. Lewis, who makes films and now lives in London, is an artist of refined sensibility and a perfectionist in fine-tuning his formal machine. The films on view, in which Toronto is clearly a character of sorts, are hyper-realist manifestations of structuralist theory, where code and communication are understood as indivisible. Lewis tells the story of Society and the City, and wraps it up in style, with a flourish; art about art, about us.

Other countries were less successful in trying to distill a good show. Austria's pavilion, while containing what in certain ways is good work, suffers from congestion and an overwrought curatorial mandate. Although clearly a lot has been done and much thought expended, the show fails to cohere. The three artists on view, Elke Krystufek, Dorit Margreiter, and the artist duo of Franziska and Lois Weinberger. They all have something to offer, but really not to each other, and therefore, not to us. Nor is it the chasm that separates the diverse practices involved that constitutes the problem. It's the predictability of the juxtapositions; the haphazardly wild and crazy hanging of Krystufek's expressionist (for the millionth time), explicit paintings that supposedly have something to do with questioning (again; again) the politics of the gaze, and the academic, and frankly boring self-referencing of Margreiter's film, which lacks the skill and charm of Lewis's at the Canadian pavilion.

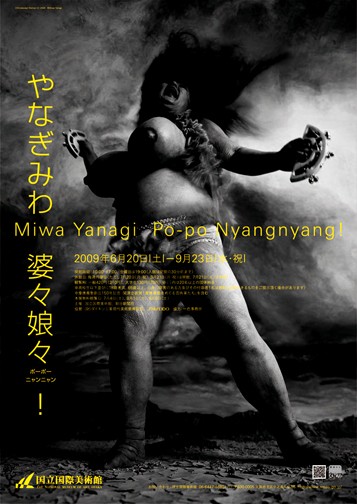

Japan's entry is sensational; it's just hard to say whether good or bad. Miwa Yanagi's "Windswept Women: The Old Girls Troupe" presents a small video that gets lost even while you're watching it. The main body of the show is a series of enormous photos (comically picture-framed as though they were on a mantelpiece, with the supporting arm in behind and at an angle from the ground) dispersed across the floor. What can only be called monstrous women, topless with misshapen breasts, waving musical instruments and bellowing, are the subject. The work is well done, for what it is. Enough said.

And then, as though there weren't another army of national shows to see, there is the thematic group show "Making Worlds", in two locations. One in what used to be called the Italian pavilion (now the Exhibition) in the Giardini, the other in the Arsenale. It is so large, to go into detail about it all would require book-length exposition. On the whole, it's great. If there are weak spots, they don't show too much, because the sweep and scale of everything will always direct our eyes to another magnificent room or installation. Some standouts: Michelangelo Pistoletto's mirror room (giant, framed, some broken, some not), Sherrie Levine's whole room (especially the surprise video projected onto the seemingly minimal painting, which we think we are looking at), and Hans-Peter Feldmann's installation, of a long table covered in rotating toys (figurines, dolls, chatchkies, etc.) with lights behind them, projecting their spinning shadows onto a white wall. You can't tell for more than a second which shadow is which: it's magical, dreamlike, a touch scary.

So there it is: what is and can only be a small sample of this year's Venice Biennale, the 53rd yet. Probably the most important show of contemporary art anywhere in the world this year, as it should be.