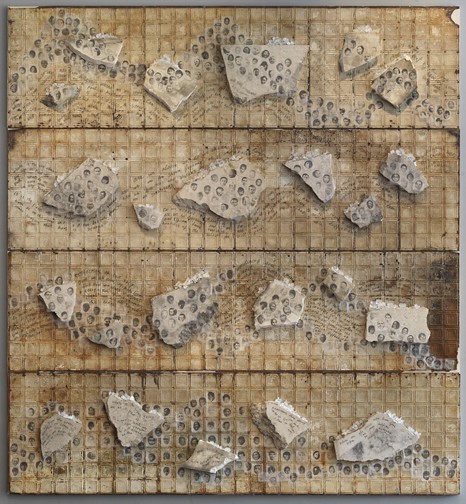

B. Amore's Street Calligraphies

Recelty Shown at Boston Sculptors

By: B. Amore - Jun 29, 2010

“What’s missing is art that seems made by one person out of intense personal necessity, often by hand.”

Roberta Smith in “Post Minimalism to the Max,” New York Times, 2/14/2010

Since childhood, I’ve been fascinated with the making of the object. My primary joy as a child came from the use of my hands, sewing at four, carving at five, incessant drawing, investigation of materials. I remember the extreme sensual pleasure of using a nail to impress an image on the hot black tar backing of an asphalt shingle on the side porch. I can still feel the intense joy as the point of the nail made a thick line through the hot tar, the marvel of the discovery.

The work I am doing now has everything to do with those early interactions between my hands, my being, and the exterior world. My hands and thoughts have been the bridge between the worlds, even the fact that I still prefer to write on this white page with a soft lead pencil is evidence of the same basic tendency. Whenever I was sick, lying in bed with the Book of Knowledge encyclopedia spread about me, cutting paper into smaller pieces and stapling them together to make small books into which I would transcribe drawings of monkeys, etc. Hours spend happily reading or making art are still primary pleasures for me. The sensations in my hands, even as I write, are actually a key to my well being. When the sense of touch is combined with sight, something is set off, a visceral feeling of deep pleasure, an excitement trembling through my core, an alertness, a sense of heightened Being.

Objects have energy. I may not, and most often do not, know of the particular history of an object that comes into my possession on the street or by some other happenstance, but there is some correspondence between my gut and my sight which propels my hand to pick it up – an inexplicable draw. Occasionally I’m repelled by the dirt or wet state of the matter, but I’m aware that when it dries it will have a different feel and that often what I perceive as less attractive actually becomes an element of interest at a later date. Some objects are magical. They carry one beyond oneself and when joined with other objects that also have a charge, then a story begins to be told.

Each piece for me is like a poem. There’s always an element of mystery, always a question about why these particular pieces have found their way into being, but there is a deep sense of “is-ness” for me when I decide to leave them be, work with the elements that seem to have found themselves. I’m the mid-wife.

The gloves are a key element and save the pieces from becoming purely abstract compositions. Each glove maintains its original gesture, as it was found. The glove, naturally, stands in for the human hand, which though literally absent, is extremely present in its alter-ego form as a glove, whose lived history is undeniably visible.

Some gloves have a tenderness, a vulnerability; sometimes because of the gesture, sometimes because being so worn, consummato in Italian. There is no way to see the glove and not be moved to begin imagining its “story.” Whenever I talk with visitor to my shows and ask them which glove is their favorite, they usually go right to the one that has touched them most deeply and begin to tell me their thoughts about it. Often they want to know where it was found. Often I can remember and sometimes I’ve forgotten. The specificity of the location is less important to me than the pure energy of the object itself. In fact, I shy away from too much specificity because I don’t want to “anchor” people on the “facts.” I really want the pieces to be read as poems, sculptural poems, in a deeply personal and evocative way.

“Material culture” is made much of these days. Somehow the importance of the “material” was subsumed by the virtual, and here we are now re-discovering the fact that the object is still with us, with its history and sculptural poetics having an innate interest, albeit somewhat transformed into a work of art. We are transitory objects ourselves. Maybe that is part of the draw. Some of these become extensions of our selves, a passing life situation, some broken down, deteriorated, given a new life in the combination with other energies.

Street Calligraphies definitely relate to the art of Japanese calligraphy – intense, lyrical sweeping brush strokes which express so much of the state of mind of the individual holding the brush at that moment. Sometimes a glove or a piece of string, or crushed paper will strike me just as forcefully as one of those intense brushstrokes. It simply couldn’t be anything other than what it IS, and hopefully in combination with other provocative forms, it may become a work of art which moves some viewers.

B. Amore is an artist, educator and writer. She studied at Boston University, University of Rome, Accademia di Belle Arti di Carrara and is the recipient of Massachusetts Cultural grants, a Fulbright Grant, Mellon Fellowship as well as a Citation of Merit Award presented by the Vermont Arts Council. She is founder of the Carving Studio and Sculpture Center in Vermont. Amore taught for many years at the Boston Museum School and has won numerous public art commissions in both the USA and Japan and is represented by SOHO 20 Gallery, New York and Boston Sculptors Gallery, Boston. Life line – filo della vita, her multimedia exhibit, that premiered at the Ellis Island Museum, is now in book form. Her most recent project and book, Invisible Odysseys, is the result of working with Mexican migrant farmworkers in Vermont. The Chelsea Creek Clipper, her permanent public art environment created from twenty-nine sea wall stones with inscriptions, was supported by the Edward Ingersoll Browne Fund and can be seen at the Condor Street Urban Wild Park in East Boston.