Aston Magna's 35th Anniversary Concert at the Clark

A scholarly, imaginative, and warm performance of Vivaldi Four Seasons and Bach concerti

By: Michael Miller - Jul 02, 2007

The Aston Magna 35th Anniversary ConcertAntonio Vivaldi, The Four Seasons, (Opus Opus 8, nos. 1-4)

J. S. Bach, Concerto in C minor for Oboe and Violin, (arranged by Wilhelm Fischer after BWV 1060) Double Concerto in D minor for two violins (BWV 1043)

Georg Philipp Telemann, Concerto for Four Violins

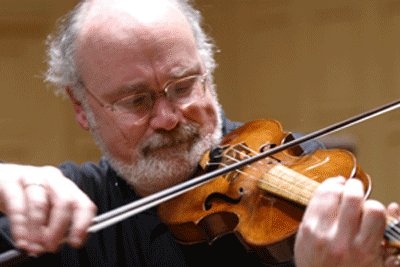

Stanley Ritchie, violin solo, Stephen Hammer, baroque oboe; with baroque orchestra led by Artistic Director Daniel Stepner

This genial concert is one of several season-opening events which invite us to reflect on the musical culture of our region, on the directions it has taken in the past and will take in the future. Playing for the first time in the acoustically superb auditorium of the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Insitute, the musicians of Aston Magna celebrated their 35th anniversary with mainstays of the baroque repertory, two double concertos by J. S. Bach and Vivaldi's Four Seasons with the surprise addition of a concerto for four violins (sic!) by Georg Philipp Telemann. Central to the occasion was the presence of the distinguished baroque violinist, Stanley Ritchie, one of the founding members of Aston Magna and five of his students from Indiana University, where he has taught early music since 1982: Andrew Fouts, Go Yamamoto, Donmyung Ahn, Janelle Davis, violins, and Jonathan Oddie, harpsichord. In fact his creative involvement with Aston Magna antedates is actual beginnings, since he began to collaborate with Albert Fuller, co-founder of the festival, in 1970. Current Music Director Daniel Stepner is ubiquitous and highly respected figure in the early music world, having been at various times concertmaster of the Handel and Haydn Society, Boston Baroque, the Boston Early Music Festival Orchestra (who played last week to great acclaim in Lully's Psyché in Great Barrington, review forthcoming), and the New Haven Symphony. He has also been Assistant Concertmaster of the Orchestra of the Eighteenth Century, who will be playing at Tanglewood later this summer.

Aston Magna, established by Albert Fuller and Lee Elman in Great Barrington in 1972, is the oldest summer festival in North America devoted to the performance of music on period instruments and in an historical style. It has been one of the most influential forces in shaping the historically informed performance of early music into the vital movement it is today, and Aston Magna's foundation 35 years ago takes us back to its formational years. The first performances in America of the Brandenburg Concertos and of Mozart symphonies in 1977 and 1978 respectively were presented by Aston Magna. It is entirely fitting that the anniversary be celebrated in such an unpretentious way, with familiar baroque masterpieces impeccably performed under Mr. Ritchie's elegant, gently virtuosic guiding spirit.

The ensemble seemed quite at home in the Clark's intimate performance space with its mellow acoustics. In a group consisting of five vioins, one viola, one cello, and one double bass gathered around a harpsichord interaction is bound to be direct and close. As Stanley Ritchie directed the Four Seasons from within his role as soloist, Music Director Daniel Stepner acted as a recessive but alert backup, almost as a mirror reflecting Ritchie's intentions to the musicians outside his eye contact, while in the Bach he exerted his own collegial but effective control, doubling with Ritchie and Stephen Hammer, baroque oboe, as soloist. Ensemble was relaxed but as precise as it needed to be. Intonation was also excellent, only occasionally wandering from pitch, a notorious problem in period performances, given the revealing absence of vibrato. As modestly as he displays it, Mr. Ritchie's virtuosity is impressive in its effortlessness and in his compelling execution of ornaments and other figurations, like arpeggios. Mr. Stepner shows no less of a command of baroque style and his instrument, and oboist Stephen Hammer offered a marvellous display of tone and phrasing, as well as a spontaneous vigor which gave his interaction with Mr. Stepner and the ensemble a vivid physicality. I can't think of a better example of the quality the Aston Magna pioneers were pursuing in their reanimation of early performance practices.

Antonio Vivaldi in his concertos for solo instrument and string orchestra, of which there are more than 500, developed a form which allowed both for tonal stability and freedom of invention and combined it often with thematic content relating to an emotional state or to some evocative scene or narrative. The Four Seasons, his most famous work (and an incredibly famous work at that, although it only became generally known to the public in the 1940's) carries this to an extreme. Not only is the program evident in the titles of the works, the details depicted—bird songs, a flowing brook, a barking dog, freezing cold, stifling heat, etc.—are marked into the score next to the phrase in question, and four sonnets describe each concerto. In the best performances the muscians throw themselves into these poetic imitations with imaginative abandon, and Stanley Ritchie and his players achieved this most vividly, assisted by the splendid acoustics of the hall. For example, the players were able to begin the first movement of spring with a true piano and develop Vivaldi's expressive fantasies with subtle and complex dynamic nuances, often shifting dynamics on a virtuosic "hairpin turn." They also indulged extensively in lively crescendi and diminuendi and made vivid use of the coloristic possibilities of their baroque instruments, especially the darker tones of the viola, cello, and double bass.

Bach's concerto for two violins in D minor, one of his most familiar pieces, seemed equally fresh and satisfying, full of energy, color, and nuance. The concerto for violin and oboe in C minor is a reconstruction of a putative early version of his well-known concerto for two keyboard instruments. The concept and execution of Wilhelm Fischer's arrangement is convincing and enjoyable, all the more sole in Aston Magna's energetic performance. A work by Telemann for four violins was added in order to showcase Stanley Richie's able students, who pretty much made the most of the piece and its unusual sonorities.

This was a lovely concert and a valuable reminder that the Berkshires rank high in the history of the early music movement.

Web: http://homepages.nyu.edu/~mjm11/index.html

e-mail: heliagoras@gmail.com