James Levine Conducts Rite of Spring

Stravinsky's Modernist Masterpiece at Tanglewood

By: Charles Giuliano - Jul 06, 2009

The opening weekend of the eight week Tanglewood season proved to be stunning. There was a capacity audience on Friday night when music director, James Levine, conducted an all Tchaikovsky program. On Saturday night, jazz/ pop pianist and singer, Diana Krall thrilled her legion of fans. On an artistic level, the Sunday afternoon performance of Levine conducting Igor Stravinsky's "Le Sacre du printemps" was a benchmark for the season. It was combined with the violinist Christian Tatzlaff for Brahms' "Violin Concerto in D. Opus 77."

Even though the radical "Rite of Spring" was composed in 1912, with a premiere on May 29, 1913 in Paris, it still proves to be a tough sell. There was a disappointingly light attendance for the afternoon concert despite the fact that there was a nice break in the weather providing a perfect ambiance for a picnic on the lawn. While there was polite applause for Levine's emotionally staggering rendering of Stravinsky it was evident that many in the audience had come for Tatzlaff who was brought back on stage for an encore after a standing ovation and a chorus of "Bravos."

After boldly presenting "Rite of Spring," a masterpiece of modernism, it was anachronistic and conservative to follow with a performance of Brahms. Even visually it was significant to see empty rows of players after the enormous orchestra, with all the extra instruments demanded by the Stravinsky score. After the overwhelming cacophony and dissonance of Stravinsky the Brahms seemed like chamber music. Which is not a critique of the superb playing of Mr. Tatzlaff, one of the leading violinists of his generation. It just would have served better to hear him perform on another program.

Having taken the risks involved in presenting one of the most demanding and radical works of 20th century music, some would argue its greatest masterpiece, this might have been an occasion for Levine to introduce another modernist work. The conductor is known for his interest and commitment to contemporary composers. Last summer, for example, there was a week in tribute to Elliot Carter who has now celebrated his hundredth birthday. Levine premiered new works by Carter this past season with the BSO. It would have been spectacular to have paired that new Carter work with Stravinsky. Levine performed the "Sacre" at Symphony Hall on the occasion of the composer's birthday.

While Levine has attempted to introduce contemporary music through the BSO and Tanglewood it has met with resistance. Patrons simply stay home while season ticket holders twist and turn in their seats. Critics don't help. In the Berkshire Eagle, for example, the review of the Carter week by Andy Pincus was harsh. Other music writers just took the week off. They may have attended but were reluctant to publish their insights. Not that I claim to have understood Carter's music but I looked to critics such as Pincus for clues to understanding the work. Since then we have been playing a CD of music by Carter in our car and enjoying it immensely. Not that I would attempt to explain why.

The most important driving force of the greatest works of art is the element of risk taking. The notion of an avant-garde is that commitment to be ahead of the crowd. To constantly push and explore; to assault the complacency of the familiar and taunt the taste of the bourgeois.

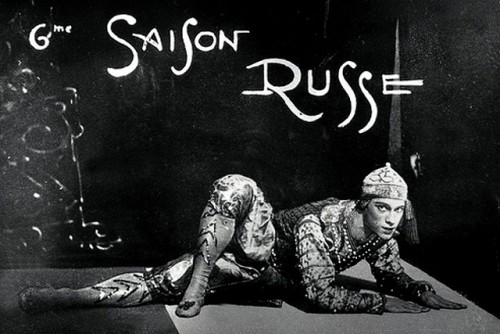

This was the mood in Paris during the early part of the 20th century. The impresario Serge Diaghilev was a matrix of radical experimentation. He started by presenting an exhibition of contemporary Russian art in 1906. (Picasso was then in the midst of developing Cubism which emerged in 1907.) He followed with concerts of Russian music and staged Mussorgsky's opera "Boris Godunov." In 1909 he returned to Paris with what would comprise the greatest company of the 20th century the Ballets Russes.

Diaghilev had the ability of bringing together the leading composers, dancers, artists/ designers and choreographers of this seminal period of modernism. The company continued in disarray after the death of Diaghilev in 1929. It actually split into two rival companies which dissolved during the Depression years. A treasure trove of the designs and costumes by artists including Picasso, Matisse, Bakst, Leger, Gabo, de Chirico, Miro, Goncharova and others was brought to Hartford, Connecticut in steamer trunks by the dancer and choreographer Serge Lifar.

There was a magical moment occurring in Hartford during the Great Depression. Lincoln Kirstein prevailed on A. Everett "Chick" Austin, Jr., the director of the Wadsworth Athenaeum, to bring George Balanchine to the city with the intent to found a dance company to perform in the museum's auditorium. In 1933 Austin purchased the Lifar Collection which consists of some 80 works including 25 costumes. Under Austin's leadership the museum collected 20th century art during a time when the Boston Museum of Fine Arts had its head stuck in the sand.

The young Stravinsky (1882-1971) was 28 in 1910 when his first commission for Diaghilev "The Firebird (L'Oiseau de feu)" premiered in June, 1910. It was followed by "Petrushka" in 1911. Over the next two years Stravinsky collaborated with the painter and scholar of Russian folklore, Nicholas Roerich. The ambition was to evoke a pagan ritual in which a virgin The Chosen One is mandated to dance herself to death as a sacrifice appeasing the gods and allowing for the emergence of spring. She is tossed into the center of a circle of maidens seemingly selected at random. This is a very different mythology than the Classical tradition of Persephone returning to earth from Hades to spend two seasons with her mother Flora.

One of the great inspirations in the art of the Romantic era is the concept of the sublime. It entails the greatest forces of nature at its most serene- sunrise, sunset- and violent- volcanoes, thunder and lightning, blizzards, tornadoes, earthquakes. In "Rite of Spring," however, Stravinsky went beyond the boundaries of Romanticism to embrace the primitive and non classical. He evoked and harnessed what Rousseau defined as the "Noble Savage." It is significant that Stravinsky was inspired by the "Primitive" in Russian folklore just after Picasso channeled the "Primitive" in creating the 1907 painting "Les Demoiselles d'Avignon" which launched Cubism.

In the process of destroying the classical tradition that culminated in Romanticism Stravinsky laid the foundation of modernism in music. His later compositions would never be so graphic, violent, or programmatic. He would become internal and cerebral appealing more to the mind and less to the gut.

In this epic adventure he had an uneasy and fragile collaborator in Vaslav Nijinsky (1890-1950). The twenty three year old dancer/ choreographer proved to be as radical in the choreography as Stravinsky in the composition. During the opening night fiasco, which resulted in a riot broken up by police, it was concluded that Stravinsky and Nijinsky had collaborated to destroy music and dance. There were only as few performances in Paris and several more in London. After that it was long considered lost as a dance although it was performed by orchestras.

It proved to be a turning point in the tragic decline of Nijinsky. He toured in South America during 1913 with the company but his lover and patron, Diaghilev, remained behind fearing an ocean voyage. On tour Nijinky was seduced by the Hungarian Countess Romola Pulszky. They married in Buenos Aires and Diaghilev was furious when they returned. By 1919 Nijinsky suffered a breakdown which ended his career. Abandoned by the dance world he was tended to by his wife until his death some three decades later.

The choreography of Nijinsky was considered to be lost. Diaghilev restaged "Sacre" in 1920 with choreography by Leonide Massine. There are other versions (as many as 200) of the dance by such choreographers as Maurice Bejart, Kenneth MacMillan, Paul Taylor, Martha Graham, Mary Wigman and Pina Bausch. Perhaps an incentive for so many versions of the dance was the inspiration of the music and the assumption that the original choreography was lost.

In the 1970's Millicent Hodson wrote a doctoral dissertation on the ballet. In 1981 she met and married the art historian, Kenneth Archer, who was an expert on Roerich. Relying on a range of archival resources they attempted to recover Nijinsky's choreography which was premiered by the Joffrey Ballet in 1987. In 1990, the Joffrey production including extensive interviews with Hodson, Archer, and Marie Rambert, a dancer in the original production, was presented as part of the Dance in America/ Great Performances series on PBS.

A video tape of that PBS presentation became a regular part of my avant-garde seminar at Boston University. In that context I have seen the Joffrey production on many occasions. Through numerous viewings it proved to be stark, riveting and shocking. It takes repeated exposure to absorb the radical impact of that remarkable work. Hodson has written about the choreography as notable for its "faceting and breaking up of movements. The movement is constantly broken into fractions. One figure may start a movement then other people will take it up in slightly different ways. What could be called cells of movement are constantly forming and splittingÂ…(there is) a great sense of restriction. And from the restriction comes much of the ballet's power."

Everything about Najinky's vision violated the canon of classical ballet. The dancers move more from their hips than legs. The feet are flat on the ground and turn out. The men in particular, walk, circle and stomp on the ground in sync with the percussion of the orchestra. In the death throes of the sacrificed Chosen One she twists and turns with the flutter, gyrations, fits and tremors of a moth in a flame. There is a petrified expression on her face as she wrenches through an exhausting emotionally draining solo. It is an agony to behold as she is eventually surrounded and devoured by a circle of wolves.

There is nothing graceful or beautiful in the traditional sense about the movement. He was striving for an impact more primal than classical. It was an instance of the raw expression of peasants wedded to high art in an uneasy cultural marriage of elements. Joffrey commented "Nijinsky's movements are not just rearrangements of classical steps. Rather he tried to invent movements that would be uniquely appropriate to 'Sacre' and to no other ballet."

Having the images of the dance so embedded it was absorbing to study Levine conducting the piece. There is of course something disembodied and disconnected about hearing the music without viewing the dance; particularly with such complex and demanding music. How else to make sense of its intense rhythms, massive percussion, or that plaintive opening passage of upper register bassoon? It is the most haunting, plaintive and primitive introduction imaginable. There is not a hint of the raging torment and violent, hypnotic rhythms that will follow.

We came to appreciate both the genius and passion of James Levine. Swirling around on his chair he attacked the score in a manner that resulted in an assault of the senses. We were in sync with his every nuance as he unleashed the sound and fury of the extended orchestra and its many special accents of percussion and color. There were the constant contrasts and textures of the strings played pizzicato or then bowed in unison like percussion instruments. One section of the orchestra pitted against another. The blast and blare of trombones as well as the undercurrent of the two tubas providing a tubby bottom sound. We found ourselves straining to identify just what exotic instrument was emitting unfamiliar sounds. Or how a more conventional instrument was pushed to the limit of its range. Like that famous bassoon solo.

In this early period Stravinsky introduced many instruments to his vast orchestras. By contrast there is also a four hand piano version of "Sacre" that preceded the final work. It is an intriguing piece to hear stripped of all those instruments. It is the skeleton and template, a blueprint of the orchestral treatment.

With masterful precision Levine clarified and kept separate and articulate every aspect of the complex score. Without that control the music easily devolves into chaos. Levine was a blur of motion and emotion. We came to hope that the chair was firmly nailed down to prevent the conductor from being launched into space.

There is an extravagance in Stravinsky's orchestration. Surely it tapped into all of the resources of Diaghilev. The cost of the production, as well as its critical failure, must have surely brought the company to the brink of disaster. But Diaghilev, it appears, the brilliant entrepreneur, reveled in the controversy. It was as the French would say un Succès de scandale. Even though it was performed only a few times, and shelved for the next seven seasons, "Sacre" was the critical event that secured the status of the company in the pantheon of dance.

Arguably every ambitious artist might hope that a premiere of their work launches a riot. It is even suggested that Diaghilev planted some hired hecklers in the audience. In art it is far more enduring to evoke outrage than indifference. But it is also true that it often takes generations to fully appreciate such breakthroughs. That seminal Picasso painting "Les Demoiselles d'Avignon," for example, remained in the artist's studio, facing the wall, for many years. It was viewed by visiting artists including Matisse who described it as a bunch of little cubes; hence, Cubism. Years later the painting was sold to a collector and eventually it was acquired by the Museum of Modern Art. Today, most visitors walk by with hardly a glance. Few comprehend that, like Stravinsky's "Rite of Spring," it was among the handful of works comprising the canon of modernism.

What a sad comment that going on a century later presenting that epic work the program has to be augmented with Brahms. "Sacre" was performed before too many empty seats. It was first performed at Tanglewood by Serge Koussevitzky in 1939 and last presented in Lenox in 2005 conducted by Charles Dutoit. Adding to that legacy Levine was just magnificent. He and the orchestra rose to the challenge. Thanks, I needed that.

Tanglewood This Week

SATURDAY, JULY 11

DIE MEISTERSINGER VON NÃœRNBERG, ACT III, JAMES LEVINE AND TANGLEWOOD MUSIC CENTER VOCAL FELLOWS AND ORCHESTRA, TANGLEWOOD FESTIVAL CHORUS AND SOLOISTS, 8:30 P.M., SHED

Following performances of Die Walküre, Act I, and Götterdämmerung, Act III, in his first Tanglewood season in 2005, James Levine continues his exploration of Wagner's operatic masterpieces with the Tanglewood Music Center Vocal Fellows and Orchestra in a concert performance of the final act of Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg. Revealing Wagner's brighter, more humorous side, the 1867 opera revolves around a singing contest and a good-natured rivalry over the love of a beautiful woman. The performance of the opera's celebratory finale also features the Tanglewood Festival Chorus, John Oliver, conductor, and a stellar professional cast, including James Morris, Johan Botha, Hei-Kyung Hong, Matthew Polenzani, and Julien Robbins, as well as Maria Zifchak, and Hans-Joachim Ketelsen making their Tanglewood debuts. The opera will be sung in German with English supertitles.

FRIDAY, JULY 10

HERBERT BLOMSTEDT AND BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, WITH PIANIST EMANUEL AX, 8:30 P.M., SHED

American-born conductor and teacher Herbert Blomstedt, who graces Tanglewood with an extended residency this summer, conducts the first of two weekend concerts anchored by Brahms' moving final symphony, the Symphony No. 4. The program also features Nielsen's Helios Overture and Beethoven's Piano Concerto No. 4, with the popular American pianist Emanuel Ax, one of the world's most highly regarded instrumentalists and a frequent and beloved presence at Tanglewood.

SUNDAY, JULY 12

HERBERT BLOMSTEDT AND THE BSO, WITH VIOLINIST JOSHUA BELL, 2:30 P.M., SHED

Continuing his work with the BSO, Herbert Blomstedt leads a program of Beethoven's Egmont Overture and Dvo?ák's rousing Symphony No. 8. One of the composer's shorter symphonies, it is also his cheeriest, infused with folk-flavored lyricism reflecting the bucolic countryside of his native Bohemia. The program also features the Bruch Violin Concerto No. 1, with the charismatic American violinist Joshua Bell, known for his multi-faceted musicality and opulent tone.

TUESDAY, JULY 14

LES GOUTS RÉUNIS, JORDI SAVALL AND LE CONCERT DES NATIONS, 8 P.M., OZAWA HALL

World-renowned gambist Jordi Savall brings his internationally renowned period-instrument ensemble Le Concert des Nations to Ozawa Hall for the first of two intriguing programs. Les Gouts Réunis ("The Tastes United") brings together music of 18th century Europe representing the stylistic "tastes" of five different countries, with works by Lully, Biber, Corelli, Avison, RodrÃguez de Hita and Boccherini.

WEDNESDAY, JULY 15

STAGE MUSIC IN THE PLAYS OF WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE, JORDI SAVALL AND LE CONCERT DES NATIONS, WITH ACTOR F. MURRAY ABRAHAM, 8 P.M., OZAWA HALL

The second concert by the internationally renowned period instrument ensemble Le Concert des Nations, led by gamba virtuoso Jordi Savall, showcases Stage Music in the Plays of William Shakespeare. The concert features music by Johnson, Locke, and Purcell, with noted actor F. Murray Abraham reading from The Winter's Tale, Macbeth, The Tempest, and A Midsummer Night's Dream.