Opening Night at Tanglewood

Michael Tilson Thomas Conducts Mahler’s Symphony No.2

By: Charles Giuliano - Jul 10, 2010

Today it is raining for the first time in a couple of weeks. What a contrast to the Monsoon of 2009 that prevailed and dampened the Berkshire season. After the recent heat wave many regard the rain as a welcome and cleansing relief.

But it was glorious last evening for the official Opening Night of the Tanglewood Music Festival. That is a bit of an oxymoron. There have been two weekends of concerts in Lenox. Most notably the multitude that attended three sold out concerts for the singer/ songwriters Carole King and James Taylor.

With the concert last night, however, Tanglewood got down to serious business.

With some prudent rescheduling what had potentially been a liability proved to be an asset.

Some time ago it was announced that maestro James Levine would be out for the season in Lenox. Yet again there was a frantic reshuffling not only to fill his slots in the program but also the all important role of teacher and mentor of the many fellows.

Generously agreeing to forego his vacation Michael Tilson Thomas, the music director of the San Francisco Orchestra, founder and artistic director of the New World Symphony, and principal guest conductor of the London Symphony Orchestra, has stepped in for Levine.

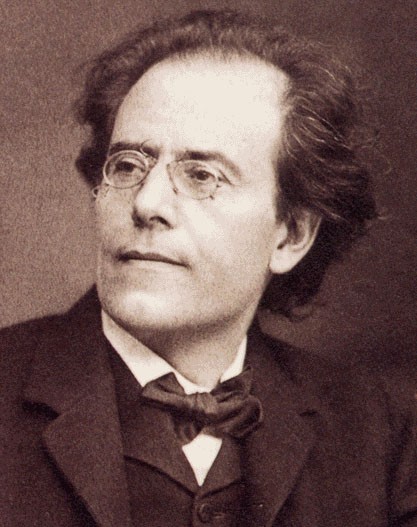

As he amply demonstrated last night while conducting Gustav Mahler’s immense, rich, visceral, lyrical and galvanic Symphony No. 2 in C minor, he is much more than a substitute or replacement for the oft ailing Levine.

Thomas has a long history with Tanglewood and the Boston Symphony Orchestra. Last summer he returned for what proved to be some of the most significant and popular intervals in the season. If that was a triumphant return to familiar territory this is more like a welcome encore.

Having him conduct Mahler was synergetic and serendipitous. Recently he has recorded the complete orchestral works of Mahler with the San Francisco Orchestra. That familiarity with the score was abundantly evident in his very sharp and physical approach to the music. He seemed to conduct not just with the baton but with his entire body. He matched the shifting emotions of the vast and complex work measure for measure.

From the thunder and angst of the first movement, to its echo with chorus in the final movement. And that poetic, dancing, light second movement. The odd emotional shift from apocryphal to lyrical seems emblematic of the early Mahler as well as the use of chorus and voice that channeled Beethoven.

The eclectic mix was not initially well received. It seems that Claude Debussy, Paul Dukas and Gabriel Pierne all walked out during a performance of the Second Symphony in Paris in 1910. They found the music to be reactionary and too much like Schubert.

Perhaps Mahler was the last gasp of romanticism. The music can be fraught and cloyingly emotional. To his critics. But for the same reasons of excess fanatically adored by his fans. Mahler is widely regarded today as among the most popular and revered of the late 19th century composers. It would be a stretch to regard him as a modernist. So he fits into that cusp when emotion, God if you will, is still the stuff of creativity.

Consider that this was about when Nietzsche proclaimed that “God is dead.” He did however pay a terrible price for that blasphemy in a precipitous descent into madness.

The Mahler second has been called “The Resurrection” for its redemptive and fervent final chorus. But the composer gave it no such title and resisted interpretation. Asked to provide program notes he wrote “… a crutch for a cripple. It gives only a superficial indication, that any program can do for a musical work, let alone this one, which is so much all of a piece that it can no more be explained than the world itself. I’m quite sure that if God were asked to draw up a program of the world he created he could never do it. At best it would say as little about the nature of God and life as my analysis says about my C minor Symphony.”

While the music, as he points out, cannot be explained given its broad program, one may discuss the performance. In particular, the two singers Stephanie Blythe, mezzo soprano, and Layle Claire, soprano. With subdued almost whispering accompaniment Blythe sang with power and authority. Layla Claire had the more daunting challenge of coming in, joining and fronting the chorus and full orchestra. She did not prove up to the task as we could scarcely distinguish her singular voice. Claire lacked the power and stamina to prevail. Even with the use of a microphone.

It was a notable flaw in what proved to be a powerful and prefect rendering. Not only did Thomas step in as a guest conductor he made the orchestra his own.

Quite deftly Thomas launched the season in Tanglewood. It augers well for what is to follow.