Roy Lichtenstein Dot.Con

Art Institute of Chicago Through September 3

By: Charles Giuliano - Jul 12, 2012

De gustibus non est disputandum.

Yes. But in contemporary art money trumps taste every time.

Consider that ultimate vulgarian, Pop artist Roy Lichtenstein (October 27, 1923 – September 29, 1997,) who is seen in a sprawling retrospective, grandly installed, organized by chronology and theme, in 20,000 square feet in the Art Institute of Chicago.

A joint effort of the Art Institute and the Tate Modern in London, the exhibition was curated by James Rondeau and Sheena Wagstaff. After closing in Chicago in early September it will travel to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., the Tate Modern and, finally, the Centre Pompidou in Paris in fall 2013.

Over five years the curators worked closely with Lichtenstein’s widow, Dorothy, and with the New York-based Roy Lichtenstein Foundation, which operates out of the artist’s home and studio in the West Village of Manhattan.

The artist created 2,000 documented works during a career that spanned almost 60 years. The show was narrowed down to 130 paintings and about 30 additional objects including drawings and some sculpture.

Lichtenstein had his first retrospective at the Guggenheim Museum in 1969, organized by Diane Waldman. The Guggenheim presented a second Lichtenstein retrospective in 1994. This is the first major museum retrospective since the artist’s death in 1997. The primary difference between this exhibition and the Guggenheim’s is the inclusion of a selection of drawings.

There are a couple of small works in an abstract expressionist manner, the juvenilia of the artist, which preceded his breakout in 1961. On a dare from Alan Kaprow he copied a Disney based cartoon of Donald Duck and Mickey Mouse fishing.

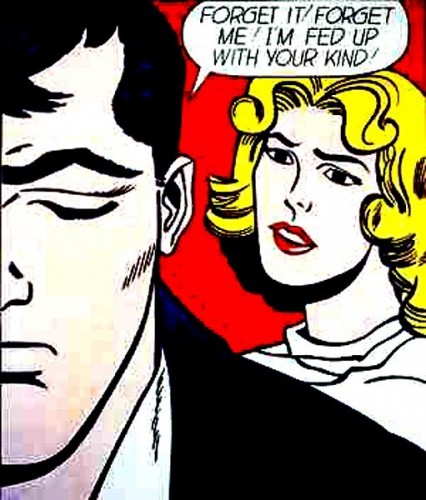

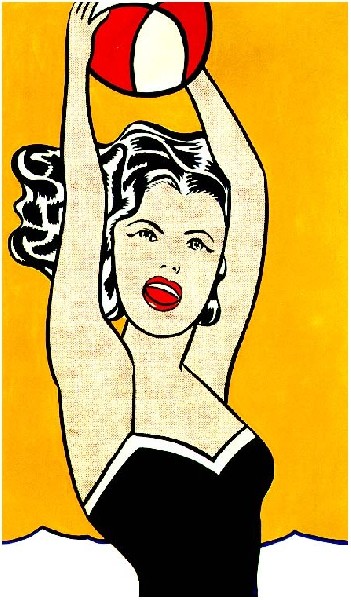

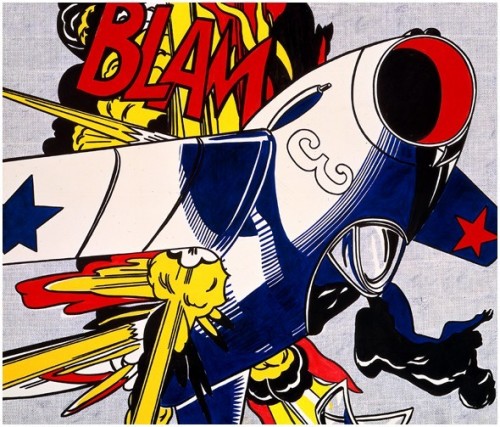

Destroying the early work, a few pieces shown in Chicago survived, for the rest of his career he created literal renderings of comics and romance illustrations, with their flat, primary colors and the Ben-Day dots of generic color separations.

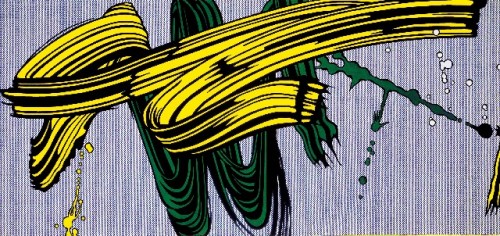

In later phases of his career he expanded beyond the initial literal appropriations to inventive spoofs of high art wedded with kitsch. He flattened out the spontaneous, swaggering, macho, drippy broad brush strokes of abstract expressionism into hilariously flat, schematic paintings. Other works explored versions of the Cubism of Picasso and Juan Gris, or the linear, sensual nudes and studio interiors of Matisse. Nothing was sacred including send ups of Monet’s Hay Stacks or van Gogh’s Room. There were abstracted sun sets, art deco paintings and sculptures, and in the late period wispy Chinese classical landscapes.

Careening through the bright, splashy, funny and colorful galleries in Chicago was not terribly different from caterwauling along the ramps of the Guggenheim.

There was that same enervating after taste of ennui. Seeing the flat, graphic, posterish paintings up close in a museum does little to improve upon viewing the work reproduced in a book, magazine, or even on line.

The point of visiting museums to view works of art is for the richness of ephemeral aspects of color, surface, brush work and technical finish that are just hinted at in reproduction. Because the premise of the artist was precisely to eliminate high art nuances we are left with nothing but the generic impact of the graphic image and its wit.

Indeed, there is much about Lichtenstein’s work that is brilliant and clever. He was vilified by professional cartoonists and illustrators who felt that he stole their stuff. The art world term is “appropriation” which is to borrow an image and enhance our understanding of the information contained in the “cartoon” by the change of context and scale through deconstruction.

Imagine, for example, reading Melville’s Moby Dick. When I was a youngster I read the original, which I enjoyed as an adventure story, as well as the Classic Comics version. Students used to read the Cliff Notes (oddly for sale in college bookstores). Now they go on line for summaries.

Ok, now consider Moby Dick as appropriated and deconstructed by multi media artist Laurie Anderson. She was inspired by visiting Melville’s Berkshire home Arrowhead. From the lawn she saw the snow covered mountains that suggested to the author the shape of the great white whale.

While in a certain sense Lichtenstein forged and copied his sources he also decoded their content. It was the fulfillment of what the German philosopher Walter Benjamin predicted in the seminal 1936 essay "The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction" Das Kunstwerk im Zeitalter seiner technischen Reproduzierbarkeit; originally published in Zeitschrift für Sozialforschung.

In a court of law appropriation evokes the concept of “fair use and editorial comment.” Artists generally win or settle those suits if they have deep pockets to fight in court. Interestingly, Lichtenstein started by taking on Disney. A no no. Nobody beats Disney. They are rich and nasty when it comes to alleged copyright infringement.

Particularly since passage of the Sonny Bono Law, in response to lobbying by Disney, Hollywood, and RCA (Elvis Presley), copyright has been extended ad infinitum beyond the original fifty years when intellectual property slid into public domain.

Remember, money trumps taste every time.

From a critical point of view I have reservations about the oeuvre of Lichtenstein. I have seen too much of his work. There didn’t seem like a pressing need for another retrospective. I do not feel particularly enriched by that saturated exposure. The work is enormously popular and it is easy to understand why museums want to display it. People come and like the work. That’s not always easy for contemporary art.

In the Boston Globe the critic Sebastian Smee critiqued the lack of adventure of the Museum of Fine Arts in its major contemporary exhibitions and acquisitions.

“What I’m trying to say” Smee wrote “is what everyone connected to the MFA knows: At this museum, given all its stupendous strengths, there’s simply too much Dale Chihuly, Katz, and Mario Testino (the fashion photographer who is the subject of an upcoming show) and not enough … well, where does one start? It’s almost impossible to imagine the MFA generating ambitious shows by the likes of, say, Cy Twombly, Cindy Sherman, Philip Guston, Martin Kippenberger, Thomas Nozkowski, Sigmar Polke, Roger Ballen, Marisol, Francis Picabia, Cornelia Parker, Richard Hamilton, Lee Krasner, Donald Judd, Juan Gris, Sheila Hicks, Kazimir Malevich, or Robert Smithson. These almost random names have nothing in common except that they are famous, critically acclaimed, 20th century, and unconnected to Maine or Cape Cod. That seems to be enough to disqualify them.”

I agree. That is indeed an interesting list of artists whose work I would rather see in depth than Lichtenstein at Chicago, or Dale Chihuly, Alex Katz and Mario Testino (don’t know that work) at the MFA. From a director’s point of view, however, what would be the bottom line for those artists? Actually, MoMA did quite well with their Cindy Sherman show this year as did the National Gallery with Malevich some time back. The ICA, when it was still on Boylston Street, before Smee’s arrival in Boston, had a stunning Cornelia Parker exhibition. From that show came the ICA’s first acquisition toward forming a permanent collection.

On May 3, 1961 the Rose Art Museum of Brandeis University opened. The founding director, Sam Hunter, with $50,000 from the Gevirtz-Mnuchin families purchased 28 works of art. The top price for any individual work, including a Lichtenstein “Forget It, Forget Me” was about $3,000. That painting was included in the Guggenheim retrospective but not borrowed for Chicago. Over the years it has frequently been loaned as one of the artist’s signature early works.

Between 2010 and 2012 his works have sold for as much as $40 million. The current record is $44.8 million for “Sleeping Girl.”

During his lifetime Lichtenstein was among the elite of richest and most successful artists. It would be interesting to know how he ranks among critics and art historians.

There is a blur between the mega art world with its focus on money, power and influence compared to the wee small voice of a critic.

As we stated at the outset, in matters of taste there can be no dispute.