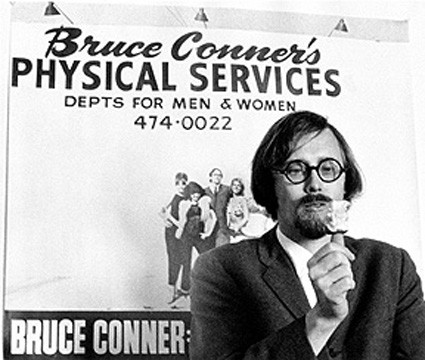

Remembering Bruce Conner, 1933-2008

A Leading Artist of His Generation

By: Charles Giuliano - Jul 13, 2008

The basement of 55 Kenwood Avenue in Newton, Mass., the title of one of his intricate, mandala drawings from the 1960s, was the studio of the artist Bruce Conner. It was the summer of 1963 and having graduated from Brandeis I was hanging out in Waltham with the musician, Mel Lyman, the actor, James Spruill, later a professor at Boston University, and inventor/ designer, John Kostick, the founder of Omniversal Design.

It was a remarkable summer which would have an impact on all of us. We were broke and it was actually Spruill who got a gig at the local hospital to pay the rent. Mel had visited Kenwood Avenue and came home with a brown paper bag of morning glory seeds which, when ingested, are hallucinogenic. At night we stared at the spirits dancing in candles and listened as Mel sang Woody Guthrie songs like the anthem "This Land Is Your Land." Jim Kweskin fell by for a session and subsequently asked Mel to join his then new Jug Band. Mel played five string, bluegrass banjo so that didn't work out and he was replaced by another banjo player. Mel moved into Kweskin's attic on Huron Avenue in Cambridge where he evolved into a world savior.

We made a field trip to see what was going down in Newton, the home and headquarters for The International Foundation of Internal Freedom (IFIF). It was the organization of two former Harvard professors, Tim Leary, and Richard Alpert. By then, Leary had parted with a group to Guadalajara, Mexico one step ahead of mounting harassment which had driven the group out of the Hitchcock Estate, in Millbrook, New York. Alpert was still floating around. He later denounced drugs and evolved as Baba Ram Das while Leary went underground and became ever more delusional.

In the basement there were Conner's assemblages involving pages from girlie magazines pasted onto folding screens and then partly torn off. There was s shabby old Victorian couch with candle wax dripped over it. The work seemed inspired by the decay of Mrs. Haversham's home in "Great Expectations" by Dickens. A sculpture of a baby like figure was made from dark brown wax. It was seated in a highchair and tangled in a cobweb constructed with shredded pantyhose. Bruce later explained that he scavanged materials for the sculptures from abandoned houses in San Francisco. It was the most remarkable work that I had then encountered. It changed my thinking about art just as Bruce provided a new paradigm of what it is to be an artist. That night, we watched a couple of Conner's films "A Movie" and "Cosmic Ray." He laughed to tell us that the nude woman riding a rocket (a reference to "Dr. Strangelove") was the wife of a famous scientist.

There were a lot of outrageous stories floating around. Like an acid night in Peggy Hitchcock's New York apartment. A very stoned Charlie Mingus apparently fired a shot gun into a wall. Fortunately nobody was hurt. Wiggy man. That Mingus could be one crazy mofo.

It was about more than getting stoned. There were ideas about exploring inner space. About being Intronauts as a corollary to Astronauts. That seeing God and tripping would somehow expand consciousness and lead to a new visionary art. Later, in 1968, at the East Hampton Gallery on 56th street, I organized an exhibition "The Visionaries" with one of the first posters by Peter Max. The exhibition became the basis of the book "Psychedelic Art" by Masters and Houston for Grove Press. It would have been great to include Bruce in that project but, by then, we had lost touch.

When Kenwood Avenue shut down, for a time, Bruce moved with his wife, Jeanne, to Brookline which he shared with what he called his "other wife" Vivian Kurz. She starred in the 1966 Andrew Meyer underground film classic "Match Girl." I was also dating Vivian as was Mel Lyman. We all met again at Bruce's show at the Rose Art Museum. Vivian took a picture of the three of us together but, when I later asked her about it, she said that there had been a problem with the camera.

For whatever reason, Bruce took a mentoring interest in me as a young artist. My training at Brandeis was fairly conservative. I had painted a portrait of Vivian when we were students. Conner was exploding my mind on many levels. There were a lot of head games going on and I viewed this as the playful mischief of psychedelic Zen monks. He told me about interesting projects like having a traveling show back in Kansas in a railroad boxcar. (He was born in McPherson, Kansas on November 18, 1933) It would be many years before I learned that this had been done by the Russian avant-garde during the Great Utopia. He described how the floor of the boxcar exhibition had been covered with marbles. A lot of his work, as I would later understand, derived from the puns and visual jokes of Marcel Duchamp.

Bruce talked about how he had dragged all of that work from San Francisco to hang out at IFIF and take part in those acid tests. An amazing stream of dignitaries passed through Newton to trip with the masters. Years later, I asked the jazz trumpeter and big band leader, Maynard Ferguson, about his visit to Kenwood Avenue. He was quite surprised by the question and didn't want to say much.

One of my Brandeis studio professors, the sculptor, Peter Grippe, was very generous in providing us with tools and materials. He was my best teacher particularly by insisting on treating us not as students but as young artists. I had a package of very large sheets of paper for woodcuts that I gave to Bruce. In turn, Bruce gave me a box of wax addressed to him at Kenwood Avenue. For a time, I held onto it but the box got lost during the many moves one makes as a young artist.

During a visit to Kenwood Avenue Bruce told me he had an old Underwood typewriter he wanted to give me. I thanked him but explained that "I'm an artist not a writer so perhaps you can give it to somebody else." He listened, then left, and came back with a baseball bat. Without a word he smashed the typewriter with a ferocious blow. I vividly recall the ribbon popping out and unrolling as it traveled across the floor. Mind blowing.

Several years later, while living in a storefront at 303 East 11th Street, my friend Jim Jacobs dropped by. I was too poor to have a phone so people visited or, in emergencies, sent telegrams. Jim told me he had an old typewriter in his car that he wanted to give me. This time I did not refuse. It seems that I was fated to start writing. Around the same time I started taking pictures when Gerry Berkery, a photo journalist, gave me an old Pentax. But that camera got stolen and it ended my picture taking for many years as I could not afford to buy another. In those days, one got along through the kindness of strangers. There was also that Zen thing of being fated by changes and listening to the inner muse.

So it was really Bruce and Jim Jacobs who got me started writing. Not long after I was a critic for 57th Street Review a fanzine published by Jock Truman of Betty Parsons gallery. That led to writing for the former Arts Magazine under the editor Gordon Brown. Then I ran into Mel who invited me to write for Avatar. That's how things happen. Strange, when you think about it, but then again, not really. It's like fate and karma and stuff.

While Bruce was living in Brookline he showed with the Hyman Swetsoff Gallery on Newbury Street. The dealer was later murdered during an encounter with rough trade. He staggered home in Bay Village lay down and bled out. The day after Kennedy was assassinated Bruce put a collage about it in the window of the gallery. At the time, I didn't know what to make of it. The nation was in mourning and Bruce was arguably the first artist to respond. It was typically bold and outrageous. He would later make a collaged movie about the Kennedy assassination which is an underground classic.

The Charles Allen Gallery on Madison Avenue represented Conner in the 1960s. It was a very small, second floor space. It appears that Allen had been formerly famous and even represented de Kooning and other abstract expressionist artists. Apparently, he was a poor business man even though he had a great eye. I would visit and Allen showed me Bruce's new work and talked about his other artists like Joe Brainard. It puzzled me that Conner, who I regarded as the most important artist I ever knew, wasn't represented by a more prestigious gallery.

Much of that was of his own doing. While brilliant and inventive that prankish, hipster side got in the way. Curators and later critics found him difficult to deal with. His career imploded largely because he didn't want to play the game. There was integrity to the work that he never compromised. Now that he is gone the obits by leading critics compare him to Rauschenberg and Warhol. His assemblages are on a par with Rauschenberg and Conner's legacy in film is equal to, if not more original than, Warhol. He just never got the hype which may in fact have been ok with him. It is about doing the work and not about fame. That is decided by others and time has a way of sorting out reputations.

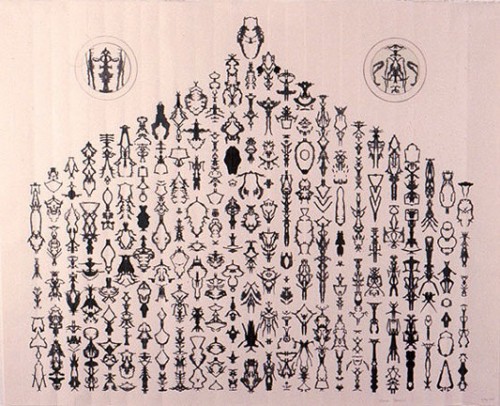

In 2000, The Walker Art Center organized a major retrospective "The Bruce Conner Story Part II." Typically, there was no "Part I." That motivated me to track him down. I managed to call him in San Francisco. It proved to be a very poignant conversation. He was, by then, in poor health. The voice on the phone was weak and hard to hear. The pace of the conversation was very slow. He was still making new work but there was only a short window during the day when he could be creative. Mostly, he was doing those ink blot drawings. We chatted a bit. He was gracious but it was clear that even a brief conversation was a physical effort. Given that he had been such a ferocious tiger it deeply saddened me then and now.