James Levine at Tanglewood

Divine Mozart and Mahler Program

By: Susan Hall - Jul 20, 2009

On Friday July 17, the Boston Symphony Orchestra under James Levine performed Mozart's A Major Piano Concerto and Gustav Mahler's Sixth Symphony in A Minor.

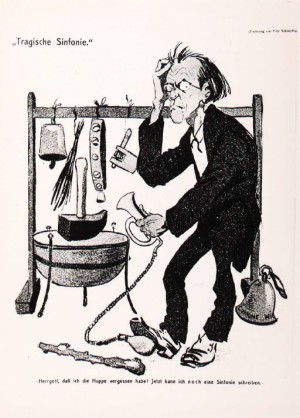

While the sky was weeping (surely Alma Mahler's word for rain) in anticipation of a performance of Mahler's "Tragic" symphony, the entering crowd was excited and eager. Alma would have appreciated the duality -- gloom and extreme beauty combined were her forte and she interpreted her husband's compositions with a full sense of the emotional impact of this duality. Alma wrote that Mahler's work was always autobiographical and programmatic in concept -- like Tchaikovsky's Sixth and Strauss's "A Hero's Life." Not exactly. But for Alma... Her ideas were often not shared by others, but they have nonetheless dominated discussion of the meaning of Mahler's work for almost a hundred years.

The evening opened brightly -- with the Mozart performed by Leon Fleisher, who spent thirty years playing with only one hand. In 1964, preparing for a tour of the Soviet Union with the Cleveland Orchestra, two of Fleisher's fingers on his right hand began to curl uncontrollably and soon clenched into a fist. Medical experts were baffled. Fleischer became artistic director of Tanglewood for a stretch, and also conducted and taught the piano.

Some 30 years after the onset of his hand paralysis, a diagnosis of focal dystonia, a neurological disorder linked to repetitive tasks, led to an experimental treatment involving Rolfing and Botox injections.

Mozart's Piano Concerto No.23 was completed on March 2, 1786 and was probably played a day or two later at one of three Mozart subscription concerts (with 120 subscribers). Marriage of Figaro was finished at the same time and would establish Mozart as the most subtle composer of opera buffa.

The Mozart piano concertos celebrate the left hand for which Mozart's own technique was famous. In this concerto, Mozart introduces a movement for wind band without the solo piano. The strings were muted, and a minor key set off particularly lively or forceful outer movements.

Fleisher turned his back to us and listened. "I think one has a tendency to take more time. One listens and takes time to listen," he says. He has learned that "silence is not the absence of music," and urges performers to play, judiciously, "as late as possible, without being late."

As he listens, he often distends time and makes the listener wait for a note as though it will never come. "It's an instant of panic: Where is it?" Fleisher acknowledged. "We're talking about nanoseconds." Evoking panic with music was a theme on Friday. Tempos judiciously imposed help create a musical mood.

In dense passages of the Mozart taken at a fast tempo some piano notes went by the wayside, but overall the beautiful, simple passages which can overexpose a pianist were perfectly lovely. "There are forces out there," Fleisher says, "and if you keep yourself open to them, if you go along with them, there are wondrous surprises."

His 81st birthday is on July 23!

No one does Mozart like Maestro Levine and this evening was no exception. The Maestro and Fleisher made a perfect pair.

Another force of nature was up next. The Mahler. This has been a year full of listening opportunities for the Mahler enthusiast. The Staatskapelle Berlin performed all ten symphonies at Carnegie Hall in the spring. Listening to these difficult scores gives a deep appreciation for the challenge of performing them – full as they are of musical ideas, so difficult to hold together.

Comments have been made about Maestro Levine's fermatas and rubatos -- tampering with tempi. I've never found any tempo Maestro took either inappropriate or distracting. In fact, I have often thought that one primary element of success is his strict sense of tempi, and holding the orchestra to them, keeping the musicians and the music on the same page. Surely on Friday, the medium-to-slow tempo he chose for the first movement heightened the drama and provided a long arc for the musical narrative. The orchestra had a chance to dig deep, and the movement's end in A major was radiant.

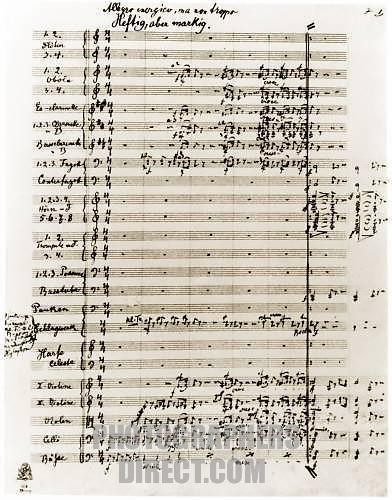

Just for fun: here's what was up on the stage: piccolo, four flutes, four oboes, English horn, clarinet in E flat and D, and clarinet in A, bass clarinet in B flat and A, four bassoons, contrabassoon, eight horns, six trumpets in B-flat and F, three trombones, bass trombone, tuba, timpani (two players), glockenspiel, xylophone, crash cymbals (several pairs) suspended cymbals, bass drum, two snare drums, deep bells, rote, tam-tam, small wooded stick, hammer, triangles, cowbells, two harps, celesta, strings. Were there eight basses?

The first movement brilliantly mixes the momentum of the march (Beethoven and Wagner used the march too, but not this persistently) with the sonata form, and the second subject -- a passionate, lyrical melody in D major said to represent Alma (by both Mahler and Alma!) in sharp contrast. At its conclusion, there was silence in the Shed. And then one voice cried out: Whoaaaa. The audience laughed. The Maestro grinned

Much is made about various elements of the Sixth, and the stories connected to them. Perhaps because the frame of the piece is so very large, we like to hunker down in detail.

The hammer, for instance, always a subject for debate, looked like a large croquet mallet on Friday. Should the hammer's blows get weaker and weaker? The hammer was chosen because its sound is dull, but Richard Strauss thought it was a shame to squander its wonderful effect. On Friday the hammer blows sounded different from all the other instruments and certainly caught my attention. The cowbells of course are pure, unpitched noise and bind the movements together. In Levine's hands, these "noises" call attention to the music produced by more conventional instruments, beautifully capable of shape and color.

The middle movements were mood pieces. As Mahler suspends the argument of the first movement, the Andante provides an oasis -- alternating between lullaby and passionate urgency. At its end, the cowbells clash loudly and something once lovely turns angry and wounded. The scherzo is a parody of the first movement -- the march redone as a dance. Underneath the fragments of old fashioned music, a chord turns major to minor over and over, until a few taps on the timpani end the movement.

Typically Mahler's first movements leave the outcome of the inner drama in question, and the Sixth is no exception. The fourth movement reveals the denouement.

The finale is a one-movement symphony in the traditional sonata duality. The march, A minor elements and the D Major subject were beautifully contrasted, all cast in monumental climaxes and an overwhelming coda after the deadening hammer blows. In the second half of the movement, all the music we've heard thus far is repeated but in reverse order: oasis, Alma music and then march. As the last vestiges of the movement's music trail off into silence, Levine gave us the sudden, stunning crash and only a minor chord was left above the drums. When we hear Levine conduct a piece, as well as we may know it, the music is freshly revealed, as though we were listening for the first time.

Writing in 1910 when Mahler was extremely unpopular, Felipe Pedrell remarked: "The final movement, presents, in a complex introduction all the principal motifs developed in the course of the piece, at times heroic, at times pastoral, reaching magnificent heights....In the entire score, a symbolic chord stands out the major chord fading into the minor, a simple technical transformation about as commonplace as could be, but in the hands of a master of evocation, this inspiration produces more than a shiver...Sooner of later, Mahler's name will occupy a page of honour in the golden book of the symphony." Hearing the symphony through Maestro Levine shows how prescient Mr. Pedrell was.

How did my neighbor, Brian Bell, the WGBH commentator on the BSO, think the Maestro created his magic: "In the focus. He has intense focus for the entire duration of a piece." Levine always knows where he's going and where he has been. How do you handle hammers and harps and cowbells in a visionary episode? Containing the music in his head, he is able to hold even a piece like the Sixth and all its disparate elements together as one.

What counts in the Levine version is the clarity and inevitability of the unfolding dramatic process, not any single specific event or gesture. Into this focus comes also Levine's deep love of music, which I have seen up close. One evening I was seated near the stage but very far left at the Metropolitan Opera. Only Maestro Levine was in my line of vision and I gave myself up to watching him. He sang the entire score of Falstaff as he conducted. And he was so happy. Ah, I thought. That's it. (How did he sing the duets, trios and quartets?)

Levine shares something else with Mahler, the conductor. In rehearsals there is a "relentless insistence on obtaining perfection in the tiniest, apparently unimportant, but in fact necessary detail out of which the irresistible sweep of the whole develops." (Berlin critic and composer Edgar Istel, contemporary of Mahler).

The morning after the concert, I was walking on Elm Street in Stockbridge, and saw a Mozart score in the back window of a car. As I approached, I read K488, A Major piano concerto on a much-thumbed edition. Next to it was a prim, hardbound edition of what I didn't know (probably Mahler), but gold-embossed in the lower right corner in block caps was JAMES LEVINE. I rushed to find a piece of paper to tuck into a windshield wiper: "The Verdi Requiem, September 2008. Can it get better than this? Yes. Gotterdammerung, April 2009. Can it get better than this? Yes. Mahler's Sixth. July 2009. One day soon, the answer will be yes again yes."

The car had gone when I returned with my note. I was glad that I had once been able to convey my appreciation directly to the Maestro. I was walking up Broadway one evening as he walked down. I approached him and asked if I could say something. He grinned and said. "Of course."

"I am so glad my time on earth has paralleled yours. You have so enriched me." He bent over and gave me a kiss.

The Mahler Sixth was the Maestro's first performance at Tanglewood over 30 years ago. May we hear many more.